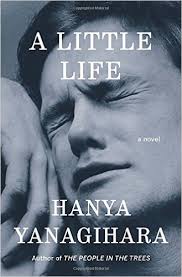

A big feud over A Little Life

In the December issue of the New York Review of Books, Doubleday executive editor Gerald Howard takes on reviewer Daniel Mendelsohn for his review of the Doubleday novel A Little Life. Howard's letter concludes: "At bottom Mendelsohn seems to have decided that A Little Life just appeals to the wrong kind of reader. That’s an invidious distinction unworthy of a critic of his usually fine discernment."

This is not the only charge levied against this particular reviewer and this particular review. As Bookforum noted, Mendelsohn was recently accused by the author Jennifer Wiener of "Goldfinching," or diminishing popular books written by and for women.

Ideally, a reviewer should always be able to parse a book from its fans. But sometimes that's impossible; sometimes a book's success becomes part of the story of the book, as inextricable as its plot and main characters. And sometimes a reviewer has to address an author's persona in the course of a review. (Here's a great example of that.) But when a review takes on the supposed audience of the book as part of a broader argument against the supposed self-victimization of college students, as Mendelsohn's review does, that's perhaps a step too far. It's one thing to extrapolate from a book's themes into a larger conversation about society. It's another thing to imagine an audience for the book and then use that imagined audience as an example of what's wrong with society.

I also find it distasteful that Mendelsohn's review overtly refers to the gendered perspective of A Little Life as "bear[ing] a superficial resemblance to a certain kind of 'woman’s novel' of an earlier age" and then immediately accuses the book of having the structure "of a striptease." The sexist condescension there — the diminishment of the book, first as a new version of a "woman's novel," and then as a stripper — feels very purposeful to me.

As Howard notes at the beginning of his letter to the editor, authors should almost always leave negative reviews alone. Rarely will you encounter a good reason to argue with a critic over a negative review; you're not going to change the critic's mind, and the argument is going to make the author look petty and small. But in this case, I'm glad that Howard stepped forward. Mendelsohn crossed a couple of very important lines in his review, and Howard was right to carry this conversation over into the public sphere.