“I’ll put ‘still emerging’ on my gravestone”: an interview with Robert Glück

“By autobiography, we meant daydreams, nightdreams, the act of writing, the relationship to the reader, the meeting of flesh and culture; the self as collaboration, the self as disintegration, the gaps, inconsistencies, and distortions of the self; the enjambments of power, family, history, and language.”

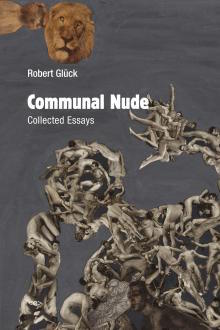

In Communal Nude: Collected Essays, this is one of the ways Robert Glück introduces New Narrative, a term he coined with Bruce Boone and Steve Abbott in the late 1970s to describe a form of prose writing emerging in the San Francisco Bay Area as a response to Language poetry and its formalist obsession with breaking apart (and breaking down) voice and context to interrogate the ways that words generate meaning. New Narrative writers included Glück, Boone, and Abbott, as well as Camille Roy, Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Mike Amnasan, Francesca Rosa, and Sam D’Allesandro—they admired the intellectual rigor of the Language poets, and the social worlds they created around their work, but wondered if this wasn’t just another straight-male dominated purity campaign.

New Narrative opened language up, but by addition rather than subtraction. New Narrative writers reveled in the excesses of voice—in sexual and romantic obsession, in gay and queer longing, in contradiction, gossip, pop culture, self-representation, shame, shamelessness, and all the possibilities and limitations of the body. Embracing the tangent, the non sequitur, and the nonlinear ramble, these writers refused to distinguish between fiction and autobiography, questioning texts in the process of creating them, and in the process creating other texts. Borrowing from the ideas of Marxism, New York School and Berkeley Renaissance poets, European critical theory, gay liberation, camp, and the dreams, schemes, and themes of their own relationships with one another, New Narrative writers rejected the conventional realism of mainstream fiction and the rigidity of the prevailing challenges to its reign.

New Narrative writing refused to separate the analytical from the personal, the societal from the intimate, the professional from the homemade, and Communal Nude is emblematic of these tenets. The book functions not just as an analysis of New Narrative, but as Glück’s informal autobiography through immersion in the work of others. The pieces in the book range from long-form essays to short rants, diary entries, introductory notes, lectures, art criticism, book reviews, and mini-biographies. It’s a historical scrapbook, and a literary collage.

“I am interested in writing that explores our pervasive sense of marginality, our loss of meaning and value, and the reconstruction of meaning and value,” Glück writes in Communal Nude, and here I talk to him about these lofty goals.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: You describe your writing practice as “theory-based,” but I think that, by centering the body and its needs, desires, and limitations, your writing is an antidote to the disembodiment of most theory. Is this part of your intention?

Robert Glück: The word theory conveys rigor, does it not? — so perhaps it’s misleading. Believe me, by the time I understand something, anyone can. I pillage theory — it interests me only when it gives me access to my own experience. Usually that does not mean whole systems of thought, often just a line or two. Except for Georges Bataille, who taught me so much. If you ever wonder what is the connection between death and sex, read Eroticism.

In a way, I think you’re making theory unnecessary by opening up the possibilities for embodied experience through writing—and, writing through embodied experience.

I guess my idea is to address the complexity of experience, not to make it add up. I gathered together the New Narrative essays in this book so they would all be in one place, but there are also essays on Kevin Costner’s Waterworld, the best lube to use, Georges Bataille, Kathy Acker, William Burroughs, essays on gardens, on certain artists, gay mid-life, Yoko Ono, O.J. Simpson….

You write, “The book becomes social practice that is lived.” In this way, you view writing as both an individual and collective process, a way to articulate and question the self, and a tool for community-building. What are the risks of this type of writing?

I wish I could put more risk into writing. I want a novel to be like performance art, where the audience and the performer share real time, where nakedness and disclosure are irreversible.

So when you say “the self is a collaborative project,” you’re challenging the narrow individualism of contemporary US politics.

Seeing the self as collaboration allows me to climb out of the box of psychology, where so much fiction is located. I can enter the intimacies of the body, so close the observations become general — it is thirst speaking, lust speaking. I can pull back into long shots that take in history, politics, the largest matter. I can do this and never abandon the precious fate of my dear characters, because I have added, not subtracted. We are either threadbare codes or larger, more porous, more glorious beings than most fiction wants to recognize.

You’re more interested in revealing contradictions than smoothing them out, and this strikes me as a loyalty to truth-telling not based on conventional middle-class norms. Is the dismantling of middle-class respectability part of your goal in writing?

I am happy if the sofa matches the drapes, but I don’t think literature should. I may set out to shock for the fun of it — why not? — but mostly I want to articulate as much of an experience as I can in as many different registers as possible, and that sometimes means saying more than is comfortable even to me. I want to say what is impossible to say because we don’t yet have a language to describe it.

In divulging your secrets, you invoke a sense of play in both writing and living, thinking and dreaming. Is there a tension between this ideal, and its practice?

I imagine there would be if I understood which was which. What is the ideal? Pouring a cup of tea for a friend? Having a job that is not alienated? Cooking a dinner with food that is nutritious and tasty?

It seems like one of your strategies in these essays is to resist closure, not just in the conventional sense, but even in terms of the very act of looking back at an essay to synthesize its meaning or impact. The final lines of the essays rarely force us to reassess the rest, and in this way they function more like conversations or monologues. Is this your intent?

Well, it’s probably just the way I think and move through the world. I am always reconsidering, re-deciding, remaking a plan. No decision is firm. No plan is final. It is sometimes very frustrating for my lover and for my publishers.

I love the prison journal you wrote after being arrested at an antinuclear protest in 1983, and held with 450 other male protesters in a tent at the Santa Rita jail for 10 days, while close to 800 female protesters were held in a nearby tent. While in general you point to desire as the formative impulse toward gay community, in this case it seems like you found a temporary community formed by the desire for change. Is there a contradiction between these two impulses?

What a good question! That essay is about negotiating my loneliness and longing in a tent with 450 men. I hope that desire for love and desire for change can go together. Certainly the best thinkers on the left wanted that. [Antonio] Gramsci felt that for a progressive movement to be viable, we should be able to find everything in it—culture, love, friendship. Not just a set of political goals, but also tuba bands. Could I substitute a bathhouse, or the broad smegmatic river that is Men Seeking Men on craigslist, for those tuba bands?

You say that, in the 1970s, gay community, “was not destroyed by commodity culture, which was destroying so many other communities; instead, it was founded in commodity culture.” Do you think that the intervening four decades of gay immersion in consumer culture have now destroyed genuine structures of community?

Yes. No.

Well, a community can be three strangers sharing an expression in an elevator. There is never not gay community. It may have migrated to the internet and social media, but what hasn’t? Or is it honeymooning in Niagara Falls? After bemoaning our preoccupation with society’s most oppressive institutions, marriage and the army, I did marry my Catalan partner, and this new civil right allows us to stay together in Sweden, where we live.

I’m sure you also agree that marriage shouldn’t be the only way to obtains rights that everyone should have access to.

I hope gay marriage will do exactly what its opponents fear — that is, change the institution. I can’t see why marriage should be limited to two people. Why not marry your dog, your toaster?

Toaster marriage would definitely function intrinsically as a critique, so I will toast to that. Some would argue that the assimilationist direction of gay politics became dominant in part due to social ostracism exacerbated by the AIDS crisis, and the drive by some gay men to appear “healthy” by conforming to straight norms. In a book that functions as an informal history, not just of your own life, but of gay culture, community-building, and creative practice over the last four decades or so, AIDS is a theme that only emerges occasionally. Was this intentional?

Nothing was intentional! It’s difficult to explain. AIDS shrank my writing horizon, Steve Abbott, Sam D’Allesandro, Bo Huston, editor George Stambolian, and a generation of queer readers as well [died due to AIDS-related causes]. Meanwhile I was doing anti-nuke work and anti-interventionist work with a gay affinity group. AIDS was personal. It meant driving my friend Ed to the hospital, watching movies with him in his bedroom, organizing a memorial, writing an obituary.

You’re now writing your “version of an AIDS memoir”—what does this look like?

The book is called About Ed. It takes me a long while to bring subject matter into fiction. Though what became the first section was originally published as “Everyman” in 1992. So you could say I have been thinking about AIDS steadily. I am glad it took me so long—now I am an old man playing with skulls. My own death was not part of the mix twenty-five years ago.

Ed Aulerich-Sugai was a Japanese-American artist and we were lovers during our twenties. Ed was a sexual mountain climber, a real explorer. Also he was a great dreamer—he could relate his dreams back through the night. The first section of About Ed is the day Ed was diagnosed. The second is his illness, his death, my mourning, and our life together in the seventies. The third is a fantasia of his dreams. I’m working on that now. I want the novel to be refracted through his dreams. I read twenty years of his dream journals to get him inside me. It was a very strange experience — for example, sometimes I would run into myself, always disappointing as it is for any eavesdropper. And do I really have Ed inside me? — or have his dreams given a shape to a feeling called Ed that was already there?

You write, “I take it as a given that the well-modulated distance of mainstream fiction is a system that contains and represses social conflict, and that one purpose of experimental work is to break open this system.” I agree wholeheartedly, but I wonder if experimental work often fails at this purpose by remaining willfully insular, a commodity for elite consumption. How can writers and other artists challenge this form of disengagement?

Like you, I write exactly what I want — not as simple as it sounds — and I put everything into it. Each new book is impossible — I am not fully engaged until I have made a book impossible to write. I’m not smart enough, I’m not skillful enough, not sufficiently empathetic—really I have to become a different person in order to write it, and I do. As for so-called difficult writing, well, usually writing is difficult not because there is a puzzle to unlock, but because the sense of time and representation is different from the reader’s expectations, yet it may be what we actually experience, and what we already accept in a painting or even a music video.

We experimentalists are so lucky — we are always emerging! We emerge till the day we die. I’ll put “Still Emerging” on my gravestone, if I have one.