Literary Event of the Week: Sarah Galvin at the Gramma Poetry party

You can choose from any number of reasons to attend the Gramma Poetry launch party at Canvas (the space formerly known as Western Bridge) this Friday night. It’s the launch party for an exciting new Seattle publisher called Gramma Poetry. There’s food. There’s booze. People are spreading rumors that there may be a bouncy castle. The band Boyfriends will play a set, followed by a dance party. Gramma author Christine Shan Shan Hou will be signing copies of her new book Community Garden for Lonely Girls. You might meet the love of your life there.

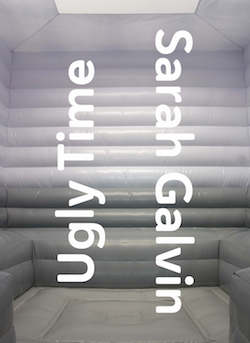

But you can find food, booze, dance parties, bouncy castles, and the love of your life virtually anywhere on a Friday night. The real reason to show up for the Gramma party is the debut of Seattle poet Sarah Galvin’s second collection and third book, Ugly Time. Galvin is one of the most entertaining readers in Seattle—hell, if she didn’t share an area code with Sherman Alexie, she’d almost definitely be the most entertaining poet in a 300-mile radius. Her readings can reduce a room full of overly serious literary types to a helpless pile of giggles.

But Galvin’s not just some stand-up comic in poet’s clothing. Her poems are crazy funny, but they’re also brilliantly crafted, with spring-loaded sentences that snap shut on your attention when your guard is at its lowest. As much as Galvin’s papercut-sharp delivery may convince you otherwise, these poems aren’t non sequiturs, or exercises in absurdity. They’re a record kept by a keen mind, a diary as real and as honest as the one you kept for a couple weeks when you were 13, only about two billion times better-written.

Take this stanza, from “I Heard She Was Fired from Catholic Arby’s;”

I climbed every historic building in town

and nothing was on top of them.

Now most of them have been demolished

to make way for buildings that lack

even the possibility of something on top of them.

The sensation of Seattle in 2017, with old disappointments being torn down to make room for newer, more antiseptic disappointments, has rarely been captured so honestly.

The poems in Ugly Time are observational and confessional and so amiable that you often don’t realize how brutal they are until you’re a few pages past. The concept of “childhood traumas” as something “like a civil war re-enactment,” playing out again and again with “my obsessive recollection of how each person fell,” is such a clear and perfect image that for a second it almost seems too obvious. (And the fact that Galvin covers it all up with a good joke about hats only adds to the power.)

Galvin’s poetry is like that: pratfalls on the edge of an abyss. “Not many people accidentally call a phone sex line/when they’re trying to reach a suicide prevention hotline,/but when you meet one it’s like meeting the president.” There’s comedy and tragedy in those lines, and that extra distance between the phone calls and the reader—the awestruck meeting of the person—gives the piece another layer of meaning. You can’t cry because you’re too busy laughing.