Thursday Comics Hangover: Kids these days

Writer Matthew Rosenberg and artist Tyler Boss’s 5-issue crime miniseries 4 Kids Walk Into a Bank is finally available in collected form, and you need to hunt down a copy immediately. Kids has so far managed to evade mainstream acclaim somehow, but its moment will come. The book is too goddamned enthusiastic, too exuberant, to ignore.

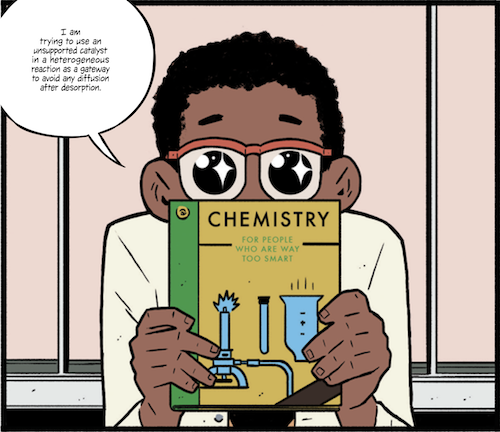

Kids is a comic about four children who become tangled in some very adult dealings, up to and including a bank robbery. They’re relatively normal kids — maybe a little more clever than the average child, but not obnoxiously so — and so they go about a life of crime in the bumbling way that children go about anything: they only understand parts of what’s going on around them, and they laugh at inappropriate things, and they are excitable in exactly the wrong ways. While they understand that they’re in a life-or-death situation, they might not understand exactly what a life-or-death situation entails. (Four of the five issues open with fantasy sequences of the kids playing video and role-playing games, where all the consequences can be wiped away with the click of a reset button. This is no mistake.)

Rosenberg and Boss match the kids enthusiasm for enthusiasm. Rosenberg’s script is a little overbearing — it is indisputably dialogue-heavy, though the text is zippier than in your average crime comic — but it is clever and funny and the characters feel real, by which I mean they’re not always likable.

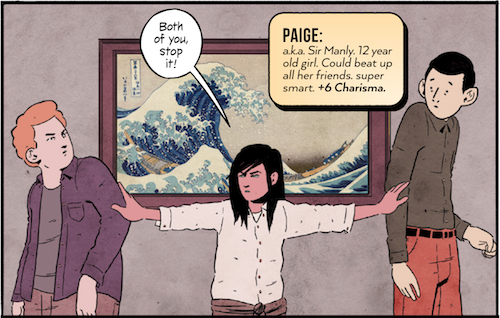

Boss’s art leans on the minimalist side of gorgeous. He’s good at stepping back and choosing just the right line to tell a character’s story. And he experiments in all sorts of fun ways. Get a load of the way he incorporates Katsushika Hokusai’s painting The Great Wave off Kanagawa into this panel:

The way he uses the curvature of the painting to add to and emphasize Paige’s inner strength is downright masterful. In this one panel — and even without any of the dialogue — we have a sense of the role she plays in her peer group and the intensity of her character. This is the kind of thing that a novelist would have to spend dozens of pages to build up, and Boss just lays it plain in the space of one little box.

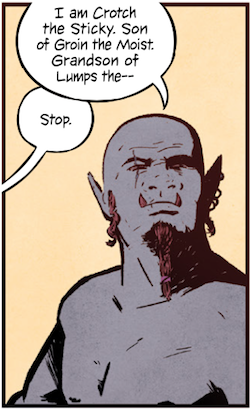

Kids is crammed full of smart-asses and crotch jokes and all kinds of puns and witty dialogue. You get the feeling that if you were to tip it upside down and shake it, some of Boss and Rosenberg’s good ideas would fall out of the book like glitter because it's so overstuffed. But it’s affecting, too — particularly in one particular parental relationship that I don’t want to expand on for fear of spoiling the story. There’s an emptiness, an airiness in the relationship that can only be left by another human being, and that ache pulses off the page.

In the end, I can’t talk about Kids without repeatedly evoking the two words I used at the beginning of this review: exuberance and enthusiasm. Rosenberg and Boss demonstrate the kind of glossy-coat enthusiasm for the magic of graphic storytelling that only talented artists at the very beginning of a comics career can muster.

But I could show you landfills packed with enthusiastic books that are no damn good at all. It’s Boss and Rosenberg’s exuberance for the characters, and for storytelling, that make it all work so well. They’re not showing off for showing-off’s sake: they’re honing their excitement and their obvious love of the craft to best serve these characters, and to best tell this story. If it’s been a while since you read a book that was purely an act of love between artists and their medium, you owe it to yourself to pick this one up.