Invented writing systems: Levert Banks and journaling the unfiltered mind

Sometimes the arrangement of coincidence changes a life. Imagine this scene: the flight is in the air, carrying hundreds of souls. In first class, Count Basie, his band is flying coach behind him. He rings the call bell to summon the flight attendant.

The attendant assigned to him, and who was sitting in the galley, was a young man named Levert Banks. He was writing in his journal when the light came on and he was called to work. Banks had been a daily journaler since being inspired to capture his feelings after the Dallas Cowboys trounced the Broncos in the 1977 season Super Bowl about a decade earlier. It was an epic rivalry, where Roger Staubach demolished former teammate and rival Cowboys' quarterback Craig Morton.

Since then? Banks told me: "I write every day. I don't write well every day, but I write every day. A day doesn't go by when something just erupts."

So he was writing in the back of the plane — on long transcontinental or international flights there was always some downtime to journal — and the buzzer went off. He tucked his book away on a shelf and got up to attend to Basie.

Job handled, Basie sated, Banks was walking back down the aisle when he sees Basie's composer. He had sheet music out and he was composing, right there on the plane, right there on his tray table.

This abstract calligraphy that, for one who knew the method, could make music from marks on paper. What a wonder! "Still, to this day, I've never seen anything as beautiful as someone writing music," Banks said.

Continuing his way through the plane, Banks stopped to chat with another passenger on this flight: Attallah Shabazz, Malcolm X's eldest daughter. She was writing in Arabic, and Banks was taken with the elegance and beauty of the calligraphy. Just the form of the text was gorgeous, like the sheet music. But more than that, it had great meaning to her. "She told me that her father had spoken Arabic and this is the way that she feels connected to him."

"So there's a very personal thing that comes with being able to express what's in your musical head, or your heart of longing, and to do it in a way that a person passing by, like me, just sees it as beautiful and can't really know what it is but knows that it's special."

With those two encounters foremost in his head, Banks returns to the galley at the back of the plane to find his journal being read by his crew. They were reading his most personal thoughts, stories of encounters and people, feelings about his job and his life. It was like they suddenly gained the ability to look into his mind and read him.

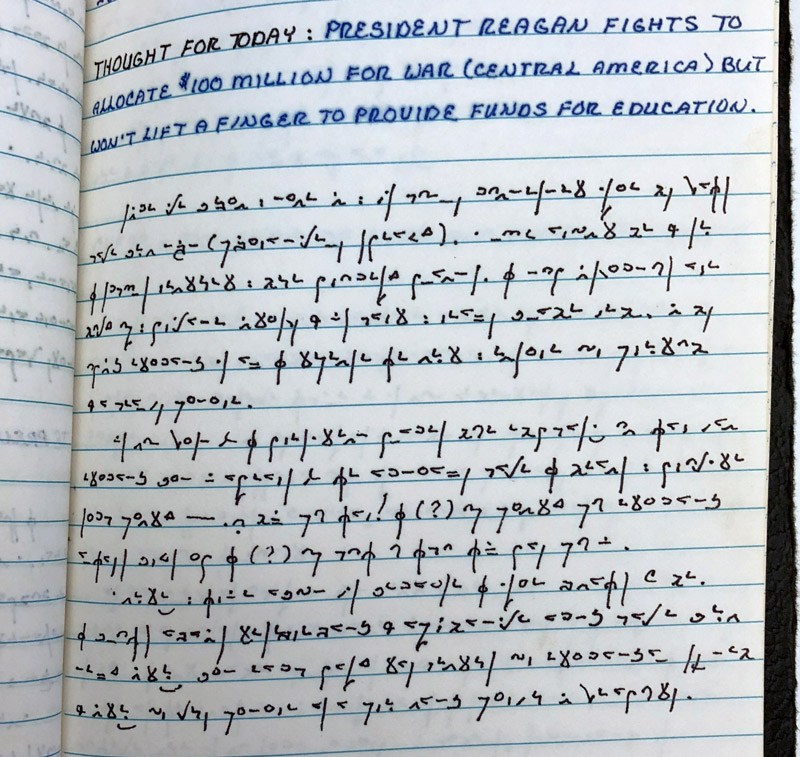

"Privacy equals don't let anyone find it. You end up not really writing the way you genuinely feel when you've shielded yourself from incrimination, or whatever else.

"It always frustrated me that being able to write what I really felt, which is the whole point of journaling in my opinion, was restricted by this security issue. So I had spent a lot of effort not letting people find it. You do put it under lock and key, hiding under your mattress."

Diaries have locks for a good reason, after all. Parents, or spouses, read other's journals for good reason, after all, however deceptive the practice — there is no faster way to learn the complex interior of someone else then if they are honest with the page, and you can access it. You either find a way to hide or lock your words up — or, perhaps, you think of a more novel way to disguise your writing.

Because you have to choose: be transparent in the journal and risk being found, or hide yourself from yourself for fear of being found. Banks knew which he would choose:

"The point [of journaling] is that it opens a space in a person as a writer that is so personal. It informs my external world. I seek out relationships where I can have honesty, like can we really just talk here, you and I? I don't know that very many people get to experience that."

So Banks made the choice to start writing in a way that could obscure his words. If Shabazz could do it through Arabic, and Basie's composer could do it through music, maybe Banks could to it, as well. Maybe he could develop a system.

Starting that day, Banks began writing in code.

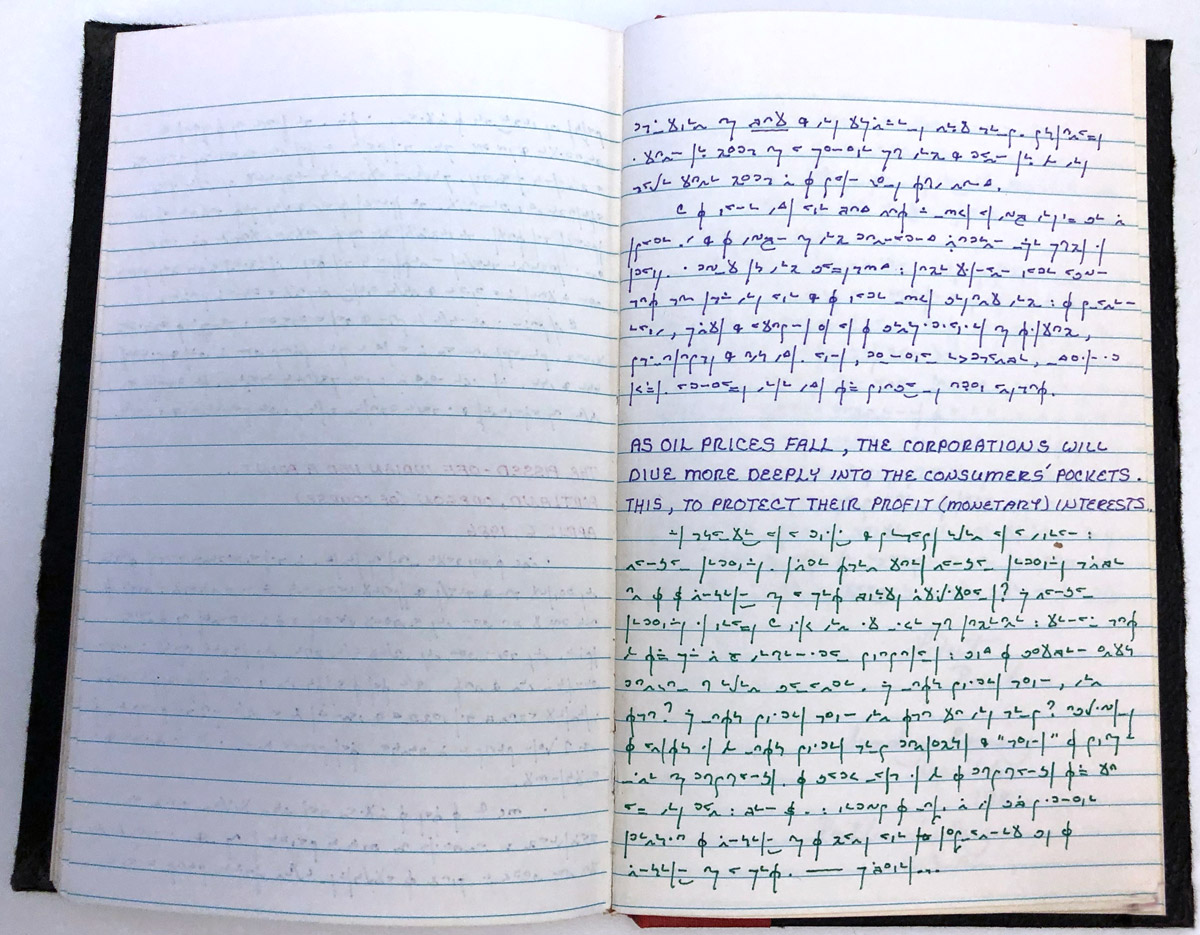

"It began as a one-to-one connection between random symbols and letters of the alphabet, and then, eventually, I saw vowel groupings, common consonant groupings, articles of speech, conjunctions, prefixes and so forth represented by single unified symbols.

"I wrote all the letters of the alphabet and I erased portions of it. I had to come back and make some refinements because of the physical structure of the way letters are written. I had to make some modifications and different treatments to make sure every character was unique.

"You're going to get tired of writing '-th', or '-ing', or 'the'. Pretty quickly it starts morphing, and a different kind of elegant form comes through. You're like 'okay, maybe I could improve that design a little bit.'

"Now you're back in second grade and it transitions to what is a 't'? What is an 'h'? What is an 'a'? I'm just putting it down because I have an idea. It happens really fast.

"And then when you get to the layer of obfuscation. I tested it with people who said, 'Okay, well, that was something, and this looks like a whatever and that looks like the word blank.

"I go back, machine it a little more and I'm like, “Thank you for that.” I never came back to that same person. I always went to the next person, and over time that's the obfuscation.

"Then, how did I treat double letters? How do I treat numbers? What am I gonna do about punctuation and contractions? Well, I've gotten rid of 99% of all punctuation, you'll never see a question mark."

"Then it said it's finished; like art work, there's a point where the canvas pushes back at the brush and says, 'I'm good.'"

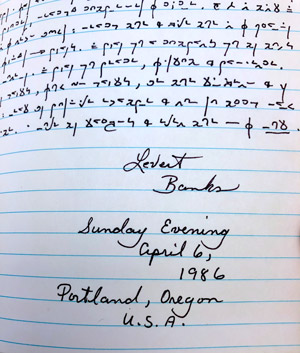

Since that day in 1988, Banks has been writing in, and over the years developing, his created language. He calls it Colan (Koh-lahn), an abbreviation of "coded language". He's taught his grown sons to read it, so that they can have access to his life when he's gone. "Well, I mean, one of my favorite movies of all time is probably Bridges of Madison County," he says.

He's also been going through the thirty years of Colan journals, and the ten that came before that in plain English, and has been working on a memoir.

I asked if he's taught anybody besides his sons to write in his language, and he tells me, no, but he's taught two people how to create their own. I say that my problem with the codes and ciphers I played with as a kid was that I could never remember them.

"Yes, but if you created it, I think, it would have worked. If you have to learn Colan, it might be difficult because you have to learn my rationale or my justification for this or that. But if I taught you how to do it yourself...?"

Colan is a reflection of Levert himself, it has a style and panache that came from his own curious, seeking mind. And it freed him to write his clearest thoughts unfiltered, which allowed him to keep an unexpurgated story of his life. He may not have published, but Banks has written more than most professional published writers.

All because of a chance encounter with Count Basie, his composer, Attallah Shabazz, and some very nosy coworkers, all lined up and flying across the country that one day back in the 80s.