Laura Da' loves the privacy of writing in public

The poet Laura Da' has been a notable name in Seattle for a good long while now. But a few years ago, it felt like Da' started appearing everywhere. She showed up on bills at group readings, and she appeared as a featured poet at book launch parties, and she taught workshops at the library. Da's ascension into the upper echelon of Seattle's literary scene happened gradually, but once you noticed that she had become an important figure, that realization felt right and good.

As you can see in the poems Da' has published with us as our Poet in Residence for the month of November, she is a meticulous and thoughtful poet. She works frequently with finely wrought couplets, often revolving around a single powerful word or image. A good Da' poem feels to me like a delicate string of glowing pearls, hung on a string of silver so finely crafted that it's almost invisible.

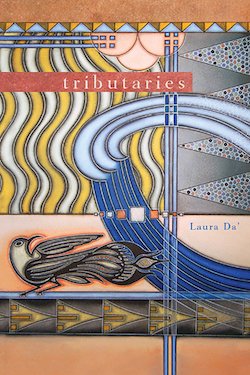

Over coffee, I ask Da' if she agrees with my assessment that she one day seemed to be ubiquitous in Seattle's poetry scene, after years on the edges. "I have a son who is eight now," Da' tells me, "and so there was a good amount of time where I was pretty limited in my ability to be out and about." She also points to the 2015 publication of her first full-length collection, Tributaries, as a moment in which her relationship to the city changed.

"I think that I've always been well connected in the indigenous poetry community," Da' says, "because I started my education at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and there are so many writers who have come out of that school. It's a tight, small community generally speaking, though it's incredibly vast in terms of talent and experience." She felt a part of that community almost immediately.

But even though she was born and raised in the Snoqualmie Valley, and lived most of her life in western Washington, breaking into this city's poetry community took more work. "Seattle is not easy to get in the door, I think, which is really unfortunate," Da' says. She says Seattle's literary community has a fair share of "gatekeepers" who aren't especially good at making new voices feel welcome.

But then "I was a Jack Straw fellow and Hugo House fellow and that really helped me," Da' says. What was it about those two programs that worked for her? "I met a lot of wonderful writers and good friends. I'm fairly introverted and shy, so usually I need an extrovert to sort of adopt me. And that was the way I found a place in the Seattle poetry community."

Da' is not one of those poets who have been writing poetry since she could first pick up a pen. She started at the Institute of American Indian Arts with "an idea that I wanted to be involved in museum studies," but then she met poet Arthur Sze, who was an instructor at the school and "a really incredible poet." His work inspired her. "I was 17 and in college and that's when I started writing poetry. I changed majors almost instantly."

What was it about poetry that spoke to Da'? "I really like the ambiguity of poetry and I also hate to be told what to do, ever. So poetry is really appealing to me," she laughs. And it appeals to her inner introvert because it's "a meditative art that feels nicely private even though it is public. There's an element of privacy that I really like."

When Da' writes a poem, she says, she's "looking at the tiniest little elements and sometimes they seem so discreet — molecular, maybe ,is a better word." She calls her poems "very finely constructed," and as she does so she mimes someone repairing a watch, leaning in close to the table and working with delicate tools to place a gear that's almost invisible to the naked eye. "They've taken me a very long time," she says.

She's very aware of the whole scope of her career, and Da' is always trying to stretch her abilities. "I'm a young writer and I don't want to move into a territory where I no longer feel like I'm an emerging writer." She cites her poem "Centaur Culture" as an attempt to do something new. "I'm trying to challenge myself with more of that sort of lyrical essay or prose-poem kind of work. Anytime I feel more established I always try to shift into something a little different."

Da' is happy with the reception her work has received, but she does think a lot about "how my poetry is categorized. I think that it's limited by mainstream publications' desire to essentialize non-white, non-dominant narratives."

Da' explains, "very often in any review [of my work,] it'll talk about how it's a Shawnee document." That's not inaccurate, of course — "I really appreciate my roots as an indigenous writer. My community is indigenous writers, and that's my most important audience, too."

That said, "I do think the dominant mainstream publication industry is much too apt to want to essentialize my work. And I think that institutional racism still allows people to view it through a lens that makes it lesser." The comments that seem to sting most for her are those reviewers who seem surprised by how finely rendered her poems are, as though indigenous poets can't be watchmakers, too.

"There are so many fantastic indigenous poets," Da' says. "There are so many poets who have been trapped by the institutional racism of publication for so long that to have people still apply that worldview feels really wrong and also sort of infuriating."

The poets who influence Da' range widely in terms of style and background. Da' gushes over poems by Danez Smith, Natalie Diaz, Sherwin Bitsui, and Cassandra Lopez. She speaks again of Sze's "respect for the reader and the reader's ability to handle the ambiguity of the unanswered."

She most likes how you can return to a single poem by Sze "every decade, and the more you've learned, the more the poem sings out to you. It's so admirable to me to create something that is beautiful on the first reading, but rewards every single subsequent reading, too."

Da's so enthusiastic about Sze's writing that she doesn't seem to realize that she could just as easily be describing her own work — these elegant couplets crafted from the smallest and most delicate materials, but which only grow finer with age.