Archives of Event of the Week

Literary Event of the Week: Lit Fix Fourth Anniversary Party at Chop Suey

UPDATE 3:39 PM: We received word that at the last minute, this edition of Lit Fix has been canceled. Apologies to all.

ORIGINAL POST 9:59 AM: When Mia Lipman moved to Seattle from San Francisco in 2011, she was delighted to find that our city had an “active, supportive literary scene.” But no matter how hard she looked, she couldn’t find her favorite kind of reading: the dive bar cabaret, combining readings with stand-up comedy and musical performances. Back in San Francisco, she says, “it was par for the course to invite bands or comics to perform between authors.” Her search for divey variety shows came up empty. “So I decided to start one myself,” Lipman says.

The boneyard of expired Seattle readings series is vast. In that graveyard, the long-running shows with devoted followings (from the Red Sky Poetry Theatre to Breadline to the recently departed — and perhaps not entirely deceased — Cheap Wine and Poetry series) are hugely outnumbered by an anonymous collection of long-forgotten attempts to get something started. A successful reading series is a community unto itself: people feel safe there, eager to return, and enthusiastic about relaxing and letting their guard down in public.

This week at Chop Suey, on Wednesday at 7 pm, the series that Lipman started, Lit Fix, celebrates its fourth anniversary — a milestone that something like 95 percent of most fledgling reading series never manage to reach. Readers include Brian McGuigan, Robert Lashley, novelist Laurie Frankel, Quenton Baker, and Kathleen Alcalá, and the $5 door charge benefits ReWA, a nonprofit that benefits the families of immigrant and refugee women with culturally sensitive assistance.

Lipman says Lit Fix’s goal as a series has always been simple. She looks for writers of all kinds — “established and new authors, poets and essayists and novelists, women and people of color and queer and traditional voices” — and asks them to share their work. “There’s never a topical theme, but I think the best nights have been when everyone onstage and in the audience winds up on the same page,” she says. A particular high point was a reading in winter of 2013, when writers Harold Taw, Corinne Manning, Indu Sundaresan, and Jason Kirk delivered “stories about transition and discovery, dirty haiku, [and] ugly Christmas sweaters” to a standing-room only crowd.

What would Lipman tell someone asking her for advice on starting a series of their own? First, she says, attend “as many readings as possible first to get a sense of what’s already out there and what kind of niche you can fill.” And then, once you know what you’re trying to do, “never be afraid to ask your dream author to read for your series! Writers (and musicians) are amazingly generous with their time and energy, and they’re often looking for new ways to connect with each other.”

To people who’s never attended Lit Fix, Lipman acknowledges that it’s “easy to retreat in winter, and that solitude has value. But being part of a community means you need to leave the house now and then to meet people where they are.” Once you exercise the effort to leave the house, “nothing feels better than cozying up with like-minded people in a relaxed space to hear someone brave open up their head and show you what’s inside.” Stop being a recluse and go see why Lit Fix has survived for four astounding years. “I promise it’ll keep you warm,” Lipman says.

Literary Event of the Week: Sarah Galvin at the Gramma Poetry party

You can choose from any number of reasons to attend the Gramma Poetry launch party at Canvas (the space formerly known as Western Bridge) this Friday night. It’s the launch party for an exciting new Seattle publisher called Gramma Poetry. There’s food. There’s booze. People are spreading rumors that there may be a bouncy castle. The band Boyfriends will play a set, followed by a dance party. Gramma author Christine Shan Shan Hou will be signing copies of her new book Community Garden for Lonely Girls. You might meet the love of your life there.

But you can find food, booze, dance parties, bouncy castles, and the love of your life virtually anywhere on a Friday night. The real reason to show up for the Gramma party is the debut of Seattle poet Sarah Galvin’s second collection and third book, Ugly Time. Galvin is one of the most entertaining readers in Seattle—hell, if she didn’t share an area code with Sherman Alexie, she’d almost definitely be the most entertaining poet in a 300-mile radius. Her readings can reduce a room full of overly serious literary types to a helpless pile of giggles.

But Galvin’s not just some stand-up comic in poet’s clothing. Her poems are crazy funny, but they’re also brilliantly crafted, with spring-loaded sentences that snap shut on your attention when your guard is at its lowest. As much as Galvin’s papercut-sharp delivery may convince you otherwise, these poems aren’t non sequiturs, or exercises in absurdity. They’re a record kept by a keen mind, a diary as real and as honest as the one you kept for a couple weeks when you were 13, only about two billion times better-written.

Take this stanza, from “I Heard She Was Fired from Catholic Arby’s;”

I climbed every historic building in town

and nothing was on top of them.

Now most of them have been demolished

to make way for buildings that lack

even the possibility of something on top of them.

The sensation of Seattle in 2017, with old disappointments being torn down to make room for newer, more antiseptic disappointments, has rarely been captured so honestly.

The poems in Ugly Time are observational and confessional and so amiable that you often don’t realize how brutal they are until you’re a few pages past. The concept of “childhood traumas” as something “like a civil war re-enactment,” playing out again and again with “my obsessive recollection of how each person fell,” is such a clear and perfect image that for a second it almost seems too obvious. (And the fact that Galvin covers it all up with a good joke about hats only adds to the power.)

Galvin’s poetry is like that: pratfalls on the edge of an abyss. “Not many people accidentally call a phone sex line/when they’re trying to reach a suicide prevention hotline,/but when you meet one it’s like meeting the president.” There’s comedy and tragedy in those lines, and that extra distance between the phone calls and the reader—the awestruck meeting of the person—gives the piece another layer of meaning. You can’t cry because you’re too busy laughing.

Literary Event of the Week: Kevin Craft at Open Books

Kevin Craft is one of the hardest-working people in Seattle literature. As a teacher, he works on literary programs at Everett Community College and University of Washington. As an editor, he ran Poetry Northwest magazine for seven years and has compiled five anthologies. As a publisher he just built a new press, Poetry Northwest Editions, that will launch with a new collection from Sierra Nelson this year. And as a writer, he’s..well, he’s published and performed a lot of poems in a lot of places, but he actually only produced one collection to his name, and that was published over a decade ago. Craft has been so tirelessly promoting the works of others for so long that his own work has received short shrift.

Until now. The University of Washington Press’s Pacific Northwest Poetry Series has shepherded a gorgeous new collection of Craft’s poetry into being. It’s titled Vagrants & Accidentals, and it feels like a book that’s been bottled up for a decade, just waiting to be introduced to an unsuspecting world.

The poetry in Vagrants is eager and obsessed with big ideas like evolution and the act of becoming. “Old Paradox” reminds the reader to “Consider that it’s difficult/if not impossible to discover the exact/moment a tadpole becomes a frog.” Life is change. If you’re not metamorphosing, you’re probably dead.

“The Descent” is its own sort of creation myth, a blend of equal parts Bible and Darwin:

There was daylight before we grew eyes.

There were grasses therefore we grew lungs.

There were speeches therefore we grew an earful.

There were speeches we grew wary of.

That first stanza is an evolutionary take on “let there be light,” one which suggests we sprang from the void to observe and partake in the world because there was a world just waiting to be observed. The second stanza gets into the idea of writing and reading — the concept that listening developed as a response to talking, and not the other way around. And then after the creation of the word came the fear of the word, the understanding that words have power and that this power can be used for good and for evil.

And that’s where the poet comes in.

The relationship between the poet and the world may not be a chicken-and-egg situation — we know the world was here before the first poet — but Craft argues that without the eyes to see and the lips to speak and the fingers to write, the world may as well not have existed at all. On that same wavelength, a Seattle without Craft’s poetry in it would be a forgettable dot on a map. He breathes life into our world, as an editor and publisher and, most definitely, as a poet.

Literary Event of the Week: First Second at Seattle Public Library

With Emerald City Comicon landing at the Convention Center, all of Seattle is suffering from a ferocious case of nerd fever this weekend. But if you can’t make it to the show, you shouldn’t feel as though you’re missing out on the fun. In fact, the after-parties and side events — all of which are open to the public, even those who don’t have an ECCC lanyard — look to be more exciting than the main event.

First of all, if you haven’t visited Seattle’s newest comic book store, Outsider Comics & Geek Boutique, you should stop by for a visit on Saturday night, when the Seattle Video Game Orchestra and Choir will give a free, all-ages concert of some of your favorite video game standards from 8 to 9 pm. Outsider Comics will be hosting a full complement of comics creators all week long, from Fraggle Rock artist Jeff Stokley to O Human Star cartoonist Blue Delliquanti. Visit their Facebook page for more details. Capitol Hill’s Phoenix Comics is hosting several events, including Seattle writer G. Willow Wilson signing books with artists Gene Ha and Babs Tarr on Friday night at 7 pm.

If you’re looking for less fuss and more commerce, Wallingford’s Comics Dungeon, which recently announced it was becoming home to a comics literacy organization named Comics for Community, Compassion and Culture, will be hosting one of their trademark huge sales, with proceeds going toward the new nonprofit’s worthy mandate to introduce more comics into libraries and schools.

But the whole point of a convention is to get out in the world, to see people and to be seen. And if that’s your goal, the Seattle Public Library downtown is hosting maybe the best ECCC-related event on Friday March 3 at 7 pm. It’s a celebration of one of the most underrated comics publishers in the United States, First Second — a New York-based publisher of (mostly) all-ages books that serve as marvelous entryways into the world of comics. First Second’s books are beautiful, with high production values and a wide array of nontraditional subjects that effortlessly draw in comics noobs.

This promises to be a fun and freewheeling night at the library: First Second cartoonists Gene Luen Yang, Box Brown, Penelope Bagieu, and Matthew Loux will take part in a panel discussion, book signing, and what can only promise to be a truly epic game of Pictionary. Loux’s brand-new book, The Time Museum, is about a young woman who takes on an internship at a time-traveling museum powered by a gigantic brain named Gregory. French cartoonist Bagieu’s comics biography of Mama Cass, California Dreamin’, will be published this month. And Brown’s biography of Andre the Giant documents the world-famous wrestler’s bizarre beginnings — Samuel Beckett used to drive the young Andre to school — and his star-studded, tragically short life.

The biggest cartoonist on the bill, of course, is Yang, whose book about race and identity, American Born Chinese is one of the best comic books — or, okay, graphic novel, if you’re snooty — of the new millennium. As an advocate of youth comics initiatives worldwide, Yang will likely serve as the (absurdly young) elder statesman of the batch, introducing the bold new cartoonists to an eager audience. And really, isn’t that what comics conventions are supposed to be all about?

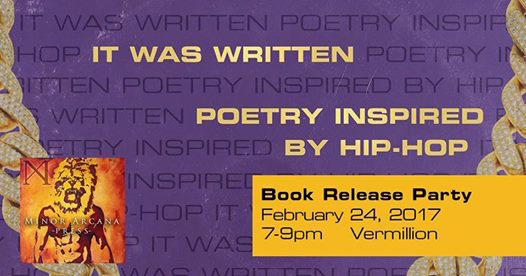

Literary Event of the Week: It Was Written book launch at Vermillion

Seems impossible in 2017, but you can still find people online who proudly announce that they don’t listen to “rap-crap.” Likewise, plenty of dudes will eagerly announce that they like all kinds of music except for country and hip-hop. Those are both statements that carry a lot of unspoken weight: if you dismiss country music and hip-hop with one broad shrug, you are basically saying “poor people make me uncomfortable and I prize comfort over everything else, including intellectual curiosity.” And dismissing an entire musical genre as garbage, especially when that medium was exclusively created by and largely fostered by young black artists, well — all together now — that’s racist.

Hip-hop is the fruit of a long, intertwined series of traditions, both musical and literary. The musical aspect is a fascinating act of reverse colonization, though which young musicians built entire cathedrals of rhythm inside tiny, repeating beats carved out of pop records. They dug into old records and found a universe of new songs there, hiding in the lines of a record. But the lyrical tradition goes back to times before record players ever existed—back to the call and response of churches, to plantations and ships crossing the Atlantic and further still. It is indisputably poetry. (For more information about the history of hip-hop, I can’t recommend Jeff Chang’s excellent 2005 book Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation enough. It’s exactly the loving, intellectual tribute that the genre needed.)

Small Seattle publisher Minor Arcana Press (slogan: “Good books for weird people”) is adding another level to the conversation between hip-hop and poetry with a new anthology titled It Was Written: Poetry Inspired by Hip-Hop. The book invites over four dozen poets to respond to hip-hop songs through verse, to open a conversation with artists they admire or struggle with (or both.) And then, in a genius move, It Was Written then flips the script by including “over 30 writing prompts* urging the reader to become a writer and join the conversation.

This Friday, Minor Arcana invites local poets including Robert Lashley and Brian McGuigan to help launch It Was Written with a book party at Vermillion. They’ll be joined by other readers including Quenton Baker, a poet who got his start as a hip-hop artist. Because the party would feel really weird without some form of live music, self-described “beat scientist” WD4D will be running the turntables at the show.

No, I’m not saying that your grandmother could become the world’s biggest Nas fan. Hip-hop is not going to be everyone’s favorite kind of music. But I am saying that hip-hop is alive and vital and inspiring conversations in a way that other kinds of art simply isn’t. By engaging with hip-hop head-on, Minor Arcana and its poets are contributing their own chapter to a history that is older than America as we know it. They’re keeping the conversation going.

Literary Event of the Week: Hugo Literary Series: Exile

Hugo House management plans the themes for their Literary Series events months in advance. They have to give the participating three writers and one musical act plenty of time to come up with new work incorporating their prompts. So it’s not like the theme of this Friday’s Literary Series event, “Exile,” was chosen as a response to the chaos unleashed by President Trump’s Muslim ban. It’s just — well, “a happy accident” isn’t the right term, obviously. More like, the dread that was floating around in the back of everyone’s minds as Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump coaxed throbbing waves of xenophobia from his base happened to be more relevant to 2017 than many of us ever expected.

So this Friday at Hugo House’s Literary Series event at Fred Wildlife Refuge, three writers and one band will present new work centering around the word “Exile.” A certain bigoted red-trucker-cap-wearing specter will undoubtedly loom over the proceedings all night. Will the artists directly engage with those affected by Trump’s Muslim ban? It’s very likely; the internet is heavy with footage of families broken across international lines for no real reason besides a narcissist’s capricious misunderstanding of what causes terrorism. Citizens are openly and seriously talking about wanting to leave America. Exile is in the air.

Hugo House selected some very fine writers for this outing of the Literary Series. Angela Flournoy, whose debut novel The Turner House won accolades for its depiction of an African-American family in Great Recession-era Detroit, is headlining. Flournoy will be returning to Seattle later this spring as part of the Seattle Public Library’s Seattle Reads… celebration, so this event serves as a kind of trial run, a way to familiarize yourself with the author before she appears in libraries all over town.

Joining Flournoy will be Portland author Megan Kruse, whose debut novel Call Me Home was a Northwest gothic about the members of an unhappy family that breaks up but can’t quite stop orbiting each other. And poet Phillip B. Williams writes beautifully about the rage and heartbreak of American cities — his “Of Darker Ceremonies” features a chalk outline around a body that “unpeels from the street” and goes on a drug-fueled rampage, “smashes every windshield” it encounters.

These three writers already focus on exiles. Flournoy wrote a whole book about the economic exiles of Detroit, the first people who were abandoned by the American Dream that seems to be slowly edging us all out. Kruse writes beautifully about emotional exile. And Williams has written about the exile of race, the uncomfortable Schrödinger's cat situation that African-Americans find themselves in: if they speak out about injustice, they’re making everything about race, but if they say nothing they’re excluded from the conversation because of their race. Together with electronic industrial pop duo Crater, these three writers will deliver strangely timely pieces that took months to write. Now is the time to speak up for exiles.

Literary Event of the Week: Paul Auster reads 4 3 2 1 at Town Hall Seattle

The thing about literature is that as one generation of giants fall, there’s always another ready to take its place. The most recent winter of titans concluded when John Updike passed away and Philip Roth announced his retirement. We’ve got a young generation on the rise with Zadie Smith and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. But the generation now at the height of its power includes names like Don DeLillo and, most especially, Paul Auster.

Every bookstore’s new arrival table is always groaning under the weight of at least one densely packed novel written by an enthusiastic young male author who aspires to join the ranks of Auster and Adichie and Updike. You know the kind of novel I’m talking about: the one that tries to thematically pack the entire universe between two covers, even as it aspires to dazzle the critics with ostentatious acts of linguistic gymnastics. It’s at least 800 pages. And it will be forgotten in 18 months or less, because those kinds of elephantine, cram-the-world-into-a-book books make for lousy debut novels.

Unlike those dense books by shallow talents, Auster’s first novel in seven years, 4 3 2 1, reflects the craft and the soulfulness that he has invested in his work for the last three decades. It’s a big gorilla-choker of a novel with a massive scope that earns its high concept. In brief, it’s the story of the life of Archibald Isaac Ferguson, the grandson of Russian Jews who came to New York City in search of their own sliver of American success. But in practice, it’s much more complicated than that.

In a series of eight long chapters, 4 3 2 1 cracks Ferguson’s story into quarters. Auster follows Ferguson’s life through four alternate timelines. He runs these lives in parallel, and it’s like a master composer applying variations to a theme. In some of the timelines, Ferguson is successful. In others, he’s a failure. In some of his lives, he falls in love and grows as a person. In other lives, he breaks bones and ruins relationships.

4 3 2 1 builds on questions that Auster has asked again and again in his work since he first published his New York Trilogy: how much of our lives are constructed on top of the quicksand of coincidence? Can there be such a thing as a successful life? Do we ever really learn lessons? Auster writes his usual metafictional intercessions into the text — Ferguson was born exactly one month after Auster, in the same city — but here they feel less like Auster’s typical commentary on the bizarreness of the act of reading and more like a deep bow toward autobiography.

At nearly 900 pages, this is a big book whose every page is earned. It’s a story by a novelist who is still learning and aspiring and interacting with literature. And Auster’s not done leaving his giant footprints on the earth. In the middle of January, Auster told The Guardian that he believed Donald Trump’s election to be “the most appalling thing I’ve seen in politics in my life,” and he made a vow: “I’m going to speak out as often as I can, otherwise I don’t think I can live with myself.” He’s not done with us yet.

Literary Event of the Week: Reading Through It Discusses Hope in the Dark

If I had to choose one, and only one, writer to help me navigate the world for the rest of my life, my choice would probably be Rebecca Solnit. Solnit is a considerate, intelligent writer; sometimes when you read her essays you can feel your own brain changing and growing to accept new information about the world. And she’s also got the power to direct the very flow of popular culture; her essay “Men Explain Things to Me” is widely regarded as the source of the word “mansplaining.”

Not many writers have the capacity and the ingenuity to identify a universal experience — in this case, that moment when a man tries to crowbar his own incorrect comprehension of the truth into a woman’s greater understanding — and give a name to it. Mansplaining has always existed, but it wasn’t a part of our vocabulary until Solnit named it. Genius isn’t the invention of something new; it’s the identification of a pattern that had always been there before, the recognition of an emotion that was never before correctly articulated. Solnit’s addition to the taxonomy of our shared experience is priceless.

For the last two months, the Seattle Review of Books and the Seattle Weekly has hosted Reading Through It, a civic-minded book club that is trying to identify the causes and meanings of Donald Trump’s presidency. Now that we’re more than a week into the Trump Administration, and now that the array of anti-science, anti-human laws and executive orders has progressed at an even more alarming rate than many of us predicted, it’s time to break out the big guns, by which I mean it’s time pit Rebecca Solnit’s brain against the world to see what happens.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities was originally published in 2004, but Solnit’s Iraq War-era manifesto has found new life in the aftermath of the 2016 election. From the first line, it slaps the despairing across the face and challenges their assumptions: “Your opponents would love you to believe that it’s hopeless, that you have no power, that there’s no reason to act, that you can’t win.”

From the keyboard of a lesser writer, one could imagine those words as the preamble to a hollow pep talk. But anyone who has read Solnit before knows that she is not someone who slathers the desperate with empty words of positivity. She is, to put it bluntly, incredibly fucking smart. And if she says there’s space for hope when everything seems hopeless, you’d have to be an idiot to bet against her.

This meeting of Reading Through It should have room for plenty of meaningful conversation: can we compare a Trump administration with the unmitigated failure of a George W. Bush administration? Are we dealing with something altogether different? Do Solnit’s old words of hope still have meaning today? Do old methods of activism work anymore, or must we arm ourselves with new rhetorical weapons? Can even one of the biggest brains in contemporary writing save us now? To that last question, the answer can only be: let’s hope so.

Literary Event of the Week: Jon Raymond reads Freebird at University Book Store

At some point, you have to figure, Jon Raymond will get sick of people comparing him to Raymond Carver. In reviews, the Portland-based author is said to “evoke” or hail “from the school of” Carver. Some reviewers even make the rare and fascinating observation that Raymond’s last name and Carver’s first name are — gasp — the EXACT SAME NAME. (Full disclosure, I very well may have made that Raymond-Carver comparison in past reviews; I’m too embarrassed to Google myself and find out.) If you work in the Northwest and you’re known for writing stories featuring short, declarative sentences and quiet epiphanies, it seems, you’ll eventually get branded with Carver’s legacy, even though it’s an obvious comparison, and one that does not withstand more than a few minutes’ examination.

If you’re reading his work through that particular lens, Raymond’s newest novel, Freebird, could be perceived as an almost-willful attempt to shake off the Carver mantle once and for all. But more likely, Raymond is just growing and changing as an artist. Freebird isn’t a book that belongs in the dusty, interior 1970s. It doesn’t reek of whiskey and regret. It feels, instead, like something new.

In fact, though Raymond has been crafting Freebird for years, it’s the rare work of fiction that feels more timely with each passing moment. It’s the story of the Singers, a California family that is constructed wholly from negative space. Grandson Aaron barely tries to bridge the chasm with his grandfather Sam, a Holocaust survivor. Anne, Aaron’s mother, is barely talking with her brother Ben, a Navy SEAL. And Anne, who works for the city of Los Angeles, is considering taking an unethical consulting deal on the side with a brown-water recycling firm — literally profiting from everyone else’s shit.

So Freebird is about the conversations we don’t have with each other — that we don’t want to have, because they’re too difficult. It’s about deciding to give up on basic human rules of conduct in exchange for a hefty profit. If you told me it was a book written for the fractured America of 2017, led as it is by a man who tosses civil behavior to the wind as he capitalizes on a fractured ideological landscape where Americans stay safely ensconced deep in their own viewpoints, I’d believe you.

The Singers are divided along political lines. There’s an age gap, and a cultural gap. History gets between everyone. And slowly everyone starts to wonder if maybe they’ve been wrong for many years. Here’s Ben, early in the book, considering the way he cheered for America’s wars:

Staring at his dad’s roof, imagining flames shooting skyward, napalm spreading over the earth, all manner of burning death, feeling his head slowly separating from his body, he began to wonder the once unthinkable: What if America was not imperiled by enemies on another continent at all? ….After almost three decades of extreme clarity on the matter, he was no longer at all sure. And without that clarity, there were other big questions to answer, too. Namely: If the enemy wasn’t out there, then what the fuck had all that violence even been for?

See what I mean? Raymond’s not some nostalgia act; he’s as vibrant as any author in the business today. Hell, it’s just like looking into a mirror.

Literary Event of the Week: Bushwick Book Club and Seattle7Writers at Town Hall

Seattle’s edition of the Bushwick Book Club is named after a popular Brooklyn series in which musicians write original music in response to a popular work of literature. Since 2010, local singer/songwriters and bands have been gathering at venues ranging from the Century Ballroom to Town Hall Seattle to the Can Can to sing songs about books including Slaughterhouse-Five, The Dark Knight Returns, and Silent Spring.

The Bushwick Book Club works best if you’re familiar with the books that the artists are singing about, of course, but even without a working knowledge of, say, Pride and Prejudice, you’ll still enjoy a nice little live anthology of Seattle-area musicians. They take turns singing a song or two each, and by the time you leave the venue at the end of the night, you’ll realize you heard an astonishing variety of music: country, folk, rock, hip-hop.

There’s something to be said for live musicians collaborating with dead authors — it’s fun to imagine Hunter S. Thompson’s annoyed response to a song that completely misses the point of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, for instance — but Bushwick Book Club also brings together Seattle authors with musicians in a kind of artistic exchange program. This Saturday at Town Hall, the Book Club collaborates with local writers’ organization Seattle7Writers to create music in response to water-themed passages from their books

Contributing authors include Daniel James Brown (whose UW rowing team history The Boys in the Boat became one of the unlikeliest Seattle-area bestsellers on its release four years ago,) Jennie Shortridge (author of the novels Love Water Memory and When She Flew,) and Jim Lynch (author of the excellent giant-squid novel The Highest Tide and the so-so Seattle World’s Fair novel Truth Like the Sun.) Musicians include Julia Massey, Joy Mills, Reggie Garrett, and Ben Mish.

Additionally, singer/songwriters Wes Weddell and Annie Jantzer, both of whom have been performing with the Book Club since the very beginning, will be performing. These two Bushwick veterans are consistently the most fun performers to watch. These aren’t novelty tunes dashed off on a toy xylophone. The two always provide a thoughtful reading of the book, and their songs are always heartfelt and well-constructed.

As anyone who’s ever watched a movie version of a beloved book can tell you, the art of adaptation is always, at best, imperfect. But the thing that saves Bushwick Book Club from awkwardness is the inclusion of literary criticism. The songwriters aren’t just relating plots in verse-chorus-verse format; they’re sharing their reading experiences, their understanding of the texts. That little bit of biography, of confession, of review is what elevates Bushwick from adaptation to conversation — and from conversation to art.

Literary Event of the Week: Sarah Schulman with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore at Seattle Public Library

“Provocative” has become a dirty word. As Donald Trump lurches toward the presidency and white nationalist Milo Yiannopoulos scores a $250,000 book deal, provocation has become synonymous with trolling, and trolling has gone mainstream. When Seattle authors Lindy West and Sherman Alexie very visibly quit Twitter last week, they demonstrated an exhaustion with provocation. We’ve had it with devil’s advocates and thought experiments that are intended to do nothing but get a reaction out of us.

Which is not to say that Conflict won’t piss you off. You likely won’t agree with all Schulman’s arguments, but that’s kind of the point. “This is not a book to be agreed with,” she writes…

…an exhibition of evidence or display of proof. It is instead designed for engaged and dynamic interactive collective thinking where some ideas will resonate, others will be rejected, and still others will provoke the readers to produce new knowledge themselves.

Her thesis in Conflict is to deflate the concept that feelings are inviolable, that, as the dust jacket suggests, too often in the 21st century, “inflated accusations of harm are used to avoid accountability.”

This is tricky stuff. Plenty of boring middle-aged white dudes have clambered up on social media platforms to sound the alarm about trigger warnings and “PC culture run amok.” Those rants aren’t worth your time; they’re the bleats of the cowardly and the closed-minded. Schulman approaches some of the same topics from a different place: “I ground my perspective in the queer,” she writes. “I use queer examples, I cite queer authors, I am rooted in queer points of view…I come directly from a specifically lesbian historical analysis of power.” Later, she notes that she “grew up in feminism.”

Schulman’s arguments are based largely in anecdotes, a method that is at once illuminating and frustrating. Her suggestion that a terse and stressful email exchange passive-aggressively stretched out over days could have been resolved by a five-minute mildly confrontational phone call is a good one. But Schulman’s story about directly engaging with a student who pursued her with behavior that could be interpreted as stalking is much less convincing; it’s out on these extremes when the theory starts to creak and groan.

Schulman’s claim that we should face the unpleasantness of conflict rather than conceal ourselves in bubbles of agreement doesn’t effectively address the 21st century’s most nonrenewable resource: attention. A human being simply doesn’t have time to engage in conflict with every available opposing viewpoint; a moral citizen of the internet has to choose her battles, and that act of selection can create its own conflicts. At some point, as West and Alexie’s exodus from Twitter proves, conflict for conflict’s sake is simply not worth it.

(Sarah Schulman reads at the Seattle Public Library with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on Tuesday, January 17th at 7 pm. The reading is free.)

Literary Event of the Week: Come discuss Citizen: An American Lyric with us tonight

Last month’s Reading Through It Book Club was a great success, a night in which nearly a hundred Seattleites gathered to discuss an America that they felt they didn’t recognize anymore. The event — a coproduction between the Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Review of Books, and Third Place Books Seward Park — didn’t provide a whole lot of answers, but it did evoke important questions of class and race and intergenerational poverty. People shared their own experiences with poverty, both from personal experience and as observers. They talked about their personal biases and how those biases might have failed them. They told jokes. They focused their view of the world through the lens of a book.

This Wednesday, I’ll be joining with Seattle Weekly editor-in-chief Mark Baumgarten and Seattle Review of Books co-founder Martin McClellan for the second Reading Through It at Third Place in Seward Park, and there will be so much to discuss.

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric first caught America’s attention when a young African-American women named Johari Osayi Idusuyi read it at a Trump rally in late 2015. Idusuyi, who was seated directly behind Trump in a video feed of the rally, pulled out Citizen and started reading it after she realized exactly the kind of event she had attended. (She told an interviewer at Jezebel that she went to the rally with “genuine intentions” to see if Trump would talk about “something of substance.” All of America would feel Idusuyi’s disappointment just one year later.) An old white couple took great offense at her literacy, and tried to get her to put the book down. She politely refused.

That whole exchange is remarkable because it’s exactly the kind of scene that would fit into the opening of Citizen. Rankine begins the book with a series of short paragraphs written in the second person detailing the many small frustrations and outrages black people experience in America today. These are not the cross-burning behaviors that come to mind when we hear about racism, but rather an array of microaggressions, thoughtlessness, and the learned normalization of whiteness.

Consider this tiny fragment of a sentence: “…he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there.” It’s a small thing, but the idea it presents is so huge: through inarticulateness or ignorance or outright aggression, he’s stating that only white writers can be great, that writers of color can never be great. Perhaps someone out there — probably a white person — thinks this is inconsequential, that it’s a minor point. But Rankine continues to add up examples like this: the way Serena Williams is treated as a black tennis player, a white man shouting the n-word in a Starbucks who gets mad when people are offended by him. It looks less like a series of accidents and more like what it is: a system.

Citizen is a book that demands conversation. This is a time that demands thoughtfulness. I hope you’ll join us tonight for a thoughtful conversation about a remarkable book.

Literary Event of the Week: Beat back the holiday doldrums with Lit Fix and Origin Stories

We’re coming up on the end of the year, and the number of available literary events are rapidly declining. Don’t get me wrong — there are still plenty of readings between now and the end of the year, but this is the one time of year when literary-minded folks are not spoiled for choice: rather than three or four good options a day, Seattle’s readers readers are lucky to get one. This must be what it’s like living in basically every other city in America.

In fact, it’s looking like Wednesday, December 14th is the last day of the normal Seattle reading calendar for 2016. It’s a big blowout of a night, with two different group readings happening on Capitol Hill, and it’s your best opportunity for a fun literary event for the next three weeks or so.

First up is the 15th installment of the Lit Fix reading series at Chop Suey. Here’s what the $5 cover at the door will get you: You’ll enjoy a rare Seattle appearance from Brooklyn novelist Leland Cheuck, whose The Misadventures of Sulliver Pong follows one Asian-American family, Forrest Gump-like, through some of the darkest moments in American history (the building of the transcontinental railroad, the internment of Japanese-American citizens during World War II.) Cheuck is joined by Seattle writer Steven Barker — whose memoir about working in the temp economy, Now for the Disappointing Part, is anything but disappointing — and the remarkably prolific Lori A. May. Seattle native Sasha LaPointe, who is best-known for her accounts of her Nooksack heritage and intergenerational trauma, capably rounds out the docket.

Like most Lit Fixes, this is a reading that celebrates writers at just the right point in their careers: when they have a book or two under their belts and they’re just starting to develop a real following. If you want to see tomorrow’s superstars in a casual, supportive environment, Lit Fix is for you.

But there’s another group reading that can’t be ignored happening across town at the Pine Box at the exact same time. Four terrific Seattle writers, each of whom enjoys a strong and devoted following, join forces to read new work along the theme of “Origin Stories.”

These are names you see a lot around town: Bellingham poet Robert Lashley, Seattle poets Sarah Galvin and Michelle Peñaloza, and Jessica Mooney, an up-and-coming writer of short fiction. Any one of these writers could headline any number of events around town, but the four of them together should make for an unforgettable evening, especially since they’re sharing new work having to do with origins, which is an incredibly potent starting point for a shared group reading. Expect personal work about pivotal decisions in the lives of these terrific writers.

There’s always a little manic energy around readings at this time of year. The audiences can get a little thin because there’s an office Christmas party or family matters that need attention. Writers are pre-annoyed by all the gaudy consumerism in the air. And the folks who do show up are likely to be misanthropic and sick of all the ceremony of holidays. In other words, late-year readings are the perfect recipe for a memorable evening. Go out and make something happen.

Event of the Week: Opting Out Early Release Party

For over a decade now, Maged Zaher’s poems have bounced between Cairo and Seattle. Somehow, he’s bridged the revolutionary Arab Spring-era Middle East and the banal tech-centric cityscape of Seattle, finding the uneasy common ground between revolutionaries and middle managers. His poems are about the world, but they’re also very specifically rooted in space; Zaher has written some of the most Seattle-y poems you’ll ever read—about our notoriously difficult dating scene, about our tech-bro culture, about corporate blandness encroaching into the arts.

Zaher recently announced on Facebook that he’s about to make a big change: he’s moving to Atlanta for personal reasons. Wherever he finds himself, Zaher has agitated for a better world. In Seattle, he has called out the homogeneity of our overly conservative, lily-white poetry scene, and he’s paid the price for his truth-telling without complaint. Zaher understands that everything is political, and that apathy is less than worthless, so he takes his stands and throws his rhetorical bombs even if they cost him a little bit of local popularity every time. One of the greatest compliments I can give him is that some of Seattle’s worst people will breathe a sigh of relief when they learn he’s leaving town.

Early next year, Seattle publisher Chatwin Books is publishing a big new satisfying collection of Zaher’s work, titled Opting Out: Early, New, and Collected Poems (2000–2015). But to mark Zaher’s exodus, Chatwin is rush-printing a few copies of Opting Out to sell at a party in the poet’s honor this Saturday night. It will be your only chance to get your hands on a copy of the collection until February.

The free pre-release party, happening at Pioneer Square antiquarian bookshop Arundel Books at 7 pm, could very well be Zaher’s last public appearance before he heads east. Wine and champagne will be provided, and Zaher will read some of his poems. Maybe he’ll read some of the Egyptian poets he translated for the remarkable anthology he edited for Alice Blue Books, The Tahrir of Poems. Maybe he’ll throw a couple more barbs at deserving targets on his way out the door, by way of a candid speech or two.

The terrific thing about Zaher is that you never know exactly what’s going to happen until it’s already happened. As a poet, as a political animal, you can’t predict what he’ll do next — you can only respond to him. I don’t want to make him out to be too much of a renegade: much of the time, Zaher is perfectly polite and generous and kind, promoting the work of a poet he loves or telling a joke about life as an information architect that leaves the South Lake Union workers in the audience darkly chuckling along with him. Those performances are just as political, just as passionate, as the rare public appearances where he burns bridges. All art — all emotion — is political, and Zaher is one of our finest revolutionaries. This city will be smaller and less interesting without him.

Arundel Books, 209 Occidental Avenue S., 624.4442, http://arundelbooks.com Free. All ages. 5 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: Indies First Party Bus

For decades, American retail employees called the day after Thanksgiving “Black Friday,” but they did so in the stockrooms and break rooms of their stores, away from customers. Managers used the term because Thanksgiving weekend sales are what typically drive a store’s yearly profits into the black. Ground-level employees called the day “Black Friday” because it was so brutal it could kill you.

At some point, “Black Friday entered the popular vernacular as the name of an official shopping holiday, and that was when holiday shopping started to get really out of hand; without “Black Friday” as a popular concept, you don’t get Target employees who have to leave their family’s Thanksgiving dinners early so they can open the store for a bunch of ungrateful yahoos who will happily murder their neighbors to get their hands on a deeply discounted flat screen TV.

To counter the grabby bottom-feeding of Black Friday, America’s small business owners pushed the idea of Small Business Saturday, a time for American to skip the mall and give their cash to local entrepreneurs, instead. Small Business Saturday didn’t seize the national consciousness like the concept of a “doorbuster,” but it’s still been a candle of hope and decency against the garish fluorescent strip lighting of corporate American commerce.

Three years ago, Sherman Alexie put a bookselling spin on Small Business Saturday with Indies First. The idea behind Indies First is simple: writers work as guest booksellers in their local independent bookstores on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. The idea took off nationwide, and now it’s become part of the holiday bookstore tradition. The American Booksellers Association chose Lena Dunham to be the public face of Indies First day nationwide, which is an odd choice. With one book to her name and a tendency to publicly make an ass of herself — and I say this as an ardent fan of Dunham’s show Girls and as someone who liked her memoir — Dunham seems like a bad choice for America’s #1 Indie Bookstore Evangelist.

Luckily, Alexie is still holding it down locally. In fact, he’s going bigger and better than ever: this Saturday, Alexie hired a party bus and stocked it full of 24 Seattle-area writers. These are big names, ranging from poets (Claudia Castro Luna, Jane Wong, Quenton Baker) to comics writers and artists (G. Willow Wilson, David Lasky, Sarah Glidden) to writers of fiction (Donna Miscolta, Nancy Rawles, Kevin Emerson) and non-fiction (David Schmader, Steven Barker) and some local book journalists (Marilyn Dahl from Shelf Awareness, yours truly.) The bus will then take the writers to three Seattle-area bookstores, where the writers will spend about an hour recommending books to customers and autographing copies of their own books.

The schedule as it stands right now — barring traffic — is:

12 pm: Third Place Books Seward Park

2 pm : University Book Store

4 pm: Elliott Bay Book Company

Come on out, meet a favorite writer, support a local business, and get a personalized gift for a loved one. After the darkness of Black Friday, it’s a blast of sunshine into the cold heart of commerce.

Literary Event of the Week: Sherman Alexie, Robert Lashley, and EJ Koh

Sherman Alexie has had a hellacious couple of years. In the summer of 2015, his mother passed away. Their relationship was always contentious and complicated, and throughout the late summer and early fall Alexie wrote dozens of poems while trying to work through his complicated grief. In December of last year, a doctor informed Alexie that he immediately needed surgery to remove a noncancerous brain tumor. The nine-hour procedure was wildly successful, but still terrifying as fuck the whole way through — afterwards, Alexie was in the ICU for a day and in the hospital for a week before beginning a long recovery regimen at home.

The year has not been all bad. As soon as he was physically able to write again, Alexie spent his post-surgery recovery period working on a memoir which incorporated that flurry of poems about his mother and new pieces about his troubled brain. And this fall, as he’s handed his upcoming memoir off to his publisher, Alexie has been everywhere around town, working so much that it seems as though he’s making up for lost time: interviewing celebrity authors like Bryan Cranston and Mary-Louise Parker, doing events with writer friends like Jess Walter and Tim Egan, and promoting the work of young writers.

This year, Bumbershoot asked the Seattle Review of Books to present a reading program, and so we thought we’d pair Alexie with two of the region’s best up-and-coming young writers: Bellingham poet and spoken word performer Robert Lashley, author of The Homeboy Songs, and a poet named EJ Koh whose first book is to be published next year. The combination was so energetic it was practically radioactive: Lashley’s poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Motherfucker at the Club” had the room vibrating with laughter, Koh’s poem about the 2014 South Korean ferry disaster led many to openly weep, and Alexie read work from his upcoming book that crossed from comedy to tragedy and back again.

Every writer, when they’re coming up against the end of the publication process, has to re-learn how to be a human. Alexie was at that point in the process at the time of the reading, and he was still coming to grips with his world turning inside out. After the reading, he was euphoric; you could tell that he had remembered why he had fallen in love with writing in the first place. It was his idea to bring the same lineup to Elliott Bay Book Company, to present the program to a wider audience. That reading happens this Friday at 7 pm, and—for those who couldn’t afford Bumbershoot tickets this year—it’s absolutely free.

Fans of Alexie’s writing will love Koh and Lashley: they share his bawdy sense of humor, his smart sense of play, and the scary raw emotion that make his readings so special. If you missed this event the first time around, you get another chance to make it right. Come help Alexie end this misbegotten year on a high note

Literary Event(s) of the Week: The Elements and Rock Is Not Dead

Autumn in literary Seattle brings with it an abundance of choice. Any given night offers at least three decent options for literary events to attend—many of them entirely free.It would be a great problem to have if it didn’t mean you missed so much fun thanks to the overstuffed readings schedules. October and November pass blithely through when-it-rains-it-pours territory and skate directly into a monsoon.

Case in point: this Saturday night delivers not one but two comics anthology debut parties. At the Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery in Georgetown, comics authors Mark Campos and Noel Franklin debut a new collection called Rock Is Not Dead with special guest cartoonists and music from Amy Denio. At Love City Love on Capitol Hill, comics collective THE HAND debuts their second anthology, The Elements. No matter where you choose to spend your Saturday night, you’re bound for a fun comics-centric evening.

The back cover copy for Rock Is Not Dead says the anthology was born out of a need to rebut KISS’s Gene Simmons, who in a 2014 interview pronounced rock and roll to be dead. “Rock ‘n Roll is not a business model,” the anthology exclaims. “Rock ‘n Roll is an attitude, a paradigm.” The comics, short fiction, and attached CD of cover songs are supposed to prove that.

Speaking as someone who has grown boundlessly bored of white men playing guitars, I remain unconvinced about the vitality of the genre, but Rock has some excellent comics in it. Franklin and Campos’s “Not Too Soon” is a beautiful, smoky broken love story set in and around the Egyptian Theater, and Wm Brian Maclean’s “Never Trust a Junkie” is a vibrant celebration of motion and color.

The Elements is thematically looser: it’s just a collective of Seattle-area artists presenting their work as a single unit. The best of the lot is Robyn Jordan’s story of a woman who desperately wants a child. She visits a tarot card reader, who then delivers some bad news. The story ends with an account of Sarah and Abraham from the Old Testament, and it concludes on a moment of decision. The confidence in Jordan’s cartooning is inspirational: a full-page depiction of the tarot reading delivers a dense spray of information in as few lines as possible, and it’s not until you give your eye time to soak in the whole thing that you can appreciate how much work went into the page.

A lot of The Elements is like that. Rachelle Duazo’s “Shower Scene” can to a prurient-minded reader represent nothing more than a comic strip about two naked people making out in a shower. But it’s really a complete history of a relationship, from beginning to end, captured in the motions and gestures of sex: one lover kneeling before another, fingers clenched together into an exploratory knot. Comics don’t get much more, well, elemental than this: raw emotion, delivered in a few representative lines on a page.

The Elements: Love City Love, 1406 E Pike St., http://twitter.com/lovecitylove. Free. All ages. 7 pm.

Rock Is Not Dead: Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore. Free. All ages. 6 p.m.

Event of the Week: A Night with Wave Books at Fred Wildlife Refuge

Wave Books has, in a relatively short span of time, become the second best poetry publisher in the Seattle area. The best, in case you’re new to town, is Port Townsend nonprofit publisher Copper Canyon Press; given that they’re probably the best poetry publisher in the country, there’s no shame here in a second-place finish.

And besides, Copper Canyon and Wave Books traffic in very different styles of poetry. Copper Canyon publishes, for lack of a better word, traditional poetry, which is to say they publish poems with the structure and the heft of generations. Their poets are continuing a long international poetry. Wave is further out on the edge. They publish experimental, risky poetry, kind of the poetic equivalent of modern art. If you were to coax your the average non-poetry-reading American into looking at a Copper Canyon title and a Wave title side-by-side, they’d most likely choose the Copper Canyon book over the Wave book simply because it would look more like what they’d expect.

But out on the edge is where the rapid advancements are made. Not every Wave Book is for everyone, but sometimes they strike some element of the collective consciousness just right, and when that happens, those books resonate through the ages. Seattle poet Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War is a perfect example of one of Wave’s winners. War, which I reviewed earlier this year, is a brilliant book combining collage, historical documents, and memoir to create something new.

This Friday at Fred Wildlife Refuge, Wave Books is hosting an evening with two Seattle poets (Choi and Wave editor Joshua Beckman) along with Wave writers Tyehimba Jess, Anselm Berrigan, and Lisa Fishman. Of those three, the one to watch is Detroit native Jess, who writes gut-punch poetry about race and music and memory that make no apologies.

One of Jess’s poems is titled “Mothafucka” and it’s dedicated to absent fathers:

will the real mother fucker please stand up?

are you the devoted fucker of mother,

one who would stay to raise his kids

to be bigger, badder, better motherfuckers?

are you one who simply fucks our mothers?

one who fucks any mother in sight?

one who, by fucking, left bastards behind?

Earlier this year, Seattle poet Maged Zaher wrote a scathing essay for the Seattle Review of Books praising Wave Books for its forward-thinking poetry, but also demanding that Wave do better in representing Seattle—Choi and Beckman pretty much represent the only Seattle writers Wave has published to date—and in representing writers of color. (Copper Canyon has done a much better job with both.) Based on the excitement I’ve seen among Seattle-area writers for this event, the community has a lot of enthusiasm for Wave; hopefully, this evening is a sign that Wave wants to do a better job of representing and including its community.

Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., wavepoetry.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: Amor Towles at FOLIO

The Count is a wondrous literary creation. He’s dignified and intelligent, but also weirdly displaced and kind of petulant. As a reader, you don’t know whether you should respond with disgust at the fact that he’s so unprepared for the roughness of the real world or with appreciation at the fact that his coping mechanism—pretending that the Revolution merely left him temporarily indisposed—is so marvelously effective. This is a character who is at once plain-faced and complex, the kind of rare protagonist who’ll live in your head for years.

Comparisons between novels and films are often misleading and unfair to both ends of the simile, but I can’t be the only reader for whom the opening pages of Moscow bring Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel to mind. Like the film, the book is densely populated with a broad and mildly cartoonish cast of characters, it’s set in a beautiful and sprawling hotel, and it’s enlivened with a broad and gracious variety of wit.

But that comparison between Moscow and Budapest is perhaps a feint masking an even more apt relationship: Anderson himself was very open about his film’s relationship to the works of Stefan Zweig, an Austrian novelist from the early half of the 20th century who went largely unappreciated while he was alive. And in fact Towles’s book is even more worthy of the claim to Zweig’s legacy than Budapest was: both Towles and Zweig write deceptively light prose that enchants a reader, and both writers use their chipper cleverness to disguise a considerable darkness underneath.

Whereas Zweig’s fiction always recoiled from the Nazi occupation that forced him to flee his home in the late 1930s, Moscow follows 30 years of Russian history from the Revolution to the dawning of the Cold War, all from within the walls of the Metropol. Some of the most brutal moments of the 20th century unfurl before the eyes of an inscrutable protagonist who tends toward heroic displays of understatement: “Let us concede that the early thirties in Russia were unkind.” That’s certainly one way to refer to famine, riots, brutality, and the rise of Stalin.

There will undoubtedly be some readers who chafe at the idea of an entire book that witnesses nearly a third of a century’s worth of a nation suffering from a sheltered aristocrat’s perspective. They are perhaps missing the point: in the Count, Towles has created a marvelous stand-in for the resilient human spirit: even in rags and imprisonment, he bears himself with dignity. Even if just in his own mind, he is a Count.

(Amor Towles reads at FOLIO: The Seattle Athenaeum tonight at 7 pm. The reading is $5.)

Event of the Week: Colson Whitehead at Seattle Public Library on Saturday, September 17th

Remember when Oprah chose Jonathan Franzen’s novel The Corrections for her book club and Franzen publicly chafed at the designation? The poor dear seemed to regret the mainstream success that came with Oprah’s seal of approval; Franzen called the books that Oprah liked “schmaltzy,” and the kiss of Oprah’s commercial approval caused him to preen over his wounded literary pride for a decade.

You will never see Colson Whitehead shying away from Oprah’s love for his latest novel, The Underground Railroad. He embraced the giant “O” stickers on the front of his book with gratitude, and he’s been riding the wave of mainstream acceptance ever since. Why did the two novelists respond so differently to Oprah’s Book Club? Well, I think part of it comes down to basic manners: Franzen is by many accounts a brat, while Whitehead has never been anything but humble and forthcoming in his many Seattle-area appearances.

But there’s more to it than that. Whitehead is a fantastic novelist, one of the best in America today. (Certainly better than Franzen.) But he’s never been able to build up the audience that he deserves because every single one of his books is different from the others. Whitehead’s debut novel, The Intuitionist, imagined an alternate New York with dueling elevator inspector guilds. John Henry Days is a big, bold examination of the John Henry mythology. Apex Hides the Hurt is a dark, nasty satire of America’s embrace of shiny surfaces. Sag Harbor is a quiet, tender semiautobiographical novel about being an African-American kid in an affluent white vacation community. And Zone One is a zombie novel. As much as readers like to think of themselves as adventurous, folks get upset when an author’s new book bears no relation to the last. Franzen succeeds in part because he writes about unhappy white families again and again; Whitehead has had difficulty gaining readers because he never follows the same path twice.

Oprah is right: The Underground Railroad is Whitehead’s best book yet. It’s the story of a runaway slave named Cora in a world where the Underground Railroad is literally a train that runs underground. The America that Cora sees in her travels is at once very like our own and wildly divergent. While the terrors that Cora encounters may not exactly resemble the historic record, they capture the rotten spirit of slavery in chilling detail.

This is the rare critically acclaimed bestseller that deserves every ounce of its adoration, and more. The hype is real. You can believe Oprah, and its scores of other fans, including some guy who took The Underground Railroad on summer vacation and can’t stop talking about its “terrific…powerful” portraiture of race in America. That fan’s name is Barack Obama.

(Colson Whitehead reads at the Central branch of the Seattle Public Library downtown on Saturday, September 17th at 7 pm. The reading is free.)