The social network

When Amazon bought the book-themed social media site Goodreads in 2013, Goodreads users went through three stages in quick succession. First, they were outraged, publishing angry posts to Facebook about how betrayed they felt. They hated that Goodreads sold out to the evil empire, wondered if their Goodreads data would be accessible to Amazon shoppers, and tried half-heartedly to find an alternative literary social media site.

Second, they mourned. They talked about how they’d never be able to trust Goodreads again, and wondered if everything they ever loved would eventually be absorbed into the Amazon mothership. They tried to pretend to be interested in downloading their data and shipping it somewhere else.

Finally, they accepted it. The people I know who used Goodreads all roundly hated Amazon’s purchase of the site, but it didn’t stop them from using Goodreads. They still post their reviews and make their reading friends and try not to mention the “A”-word, as though their silence could somehow change the reality of the situation. It continued this way for three years.

But last week, the very coolest people on my social media feeds started talking about a new literary-themed social network called Litsy. Like the coolest new social networks, it’s only available as an app for iPhones right now, though the founders are apparently promising an Android app in the near future. And it is, as someone I follow on Facebook put it, a cross between Goodreads and Instagram. As Litsy describes itself on its website:

Share bookish moments with Quotes, Reviews, and Blurbs. Measure Litfluence to discover your “bookprint” in the world. Explore recommendations from readers, not algorithms.

Oh yeah, want to organize your reading list? Our app has stacks for that, too!

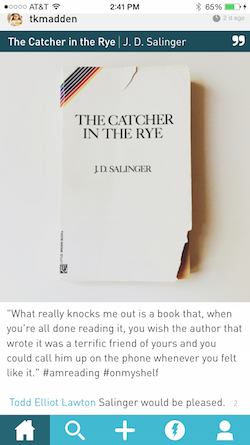

I joined Litsy a few days ago to try it out. (If you’re on there, my user name is PaulConstant.) The appeal of Litsy is certainly easy to understand: it’s a candy-colored world of easy-to-read fonts and photographs. It’s a design that inspires you to take pictures of your favorite quotes, selfies with your beloved books, and artsy photos of your shelves. Everything is kind of slow at the moment—in the five days since I’ve learned of Litsy, it seems to have spread around my immediate community of friends the way pinkeye spreads through a kindergarten class, so presumably Litsy’s founders are experiencing a scalability problem at the moment — but the schtick is pretty clear as soon as you sign up.

I’m not especially persuaded by Litsy on a personal level, much for the same reason I never liked the trend of throwing silent reading parties: it adds a weirdly performative element to the solitary pursuit of reading that never appealed to me. It’s impossible to attend a silent reading party without judging what other people read and, in return, worrying about what people think of the book that you brought along. Judging other people’s reading is a perfectly enjoyable pastime, by the way, and there’s no shame in it; I judge bookshelves at parties and read spines on the bus. But when everybody is seeing what you read and everybody is aware of being seen while reading, it adds an uncomfortable meta-level to the experience that makes me uncomfortable.

That said, there’s nothing wrong with Litsy, or with silent reading parties. Everybody makes their reading life public in one way or another; I co-own a website that publishes the opinions of people who read books, for crying out loud, so obviously I don’t think there’s any shame in that. If Litsy appeals to you, you should join up and use it. And if you join Litsy, you should friend me, too; maybe the joyousness of your sharing will inspire me to rethink how I approach the site.

But I do have some problems with the scale and scope of Litsy. I hate that you can only review books in one of four ways: Pick, So-So, Pan, or Bailed. It’s so simple it’s stupid. And all of the ways to react to the book — I’m not quite sure how “Blurb” is different from “Review,” to be honest — only allow you to use 250 characters at the most. To me, this seems like the biggest problem with Litsy: its refusal to allow lovers of words to respond to long collections of words with their own words. Granted, not every book review needs to be five thousand words long, but presumably most reading experiences are a little more substantial than just over two tweets’ worth of writing.

Again, I know I’m biased toward wordy responses to books. And I know that the internet is becoming an image-based communication medium. I just don’t know if I’m ready for the first post-literate literary social network, a place where you can fetishize the book as an object in a series of photos but you can’t discuss what moved you about the book unless your experience is roughly 125 words or less.

The world is littered with failed attempts at social networks — most recently Ello and Peach — because it’s hard to convince people to migrate to a new online home once they’re already invested in one. And Goodreads has a hell of a head start on Litsy. But it’s possible that Amazon’s involvement might be enough to convince the booksellers and librarians of Goodreads to pack up and move to higher (moral) ground. Of course, there’s nothing to stop Amazon from buying Litsy once that happens, too. In more ways than one, no online community is safe.