Thursday Comics Hangover: The Superman trick

In case you were staring out at sunny skies and planning what to do this weekend, let me just make one thing abundantly clear: Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice is every bit as terrible as you’ve heard. It is not so-bad-it’s-good. It’s just bad: inept, crass, soulless, mean-spirited, and dumb. Don’t pay money to see it.

But this isn’t another review of that movie (the world doesn’t need any more of those) and it’s not another middle-aged white dude whining about his childhood being stolen from him (the world didn’t need one of those). Instead, I want to talk particularly about one commonly held belief: the concept that Superman is hard to write. If you Google the phrase “Superman is hard to write,” you’ll get over 2.6 million results, featuring articles with titles like “The Difficulty of Writing Superman” and “3 Reasons It’s So Hard to Make Superman Interesting.” This idea is absolute bunk, and I’ll explain why.

Here it is: A good Superman story is an inward-facing story. The conflict in a Superman story is almost never external. In fact, they’re almost always internal. Everyone imagines that Superman is hard to write because he’s invulnerable, and super-strong, and has super-senses, and so on and on and on. That doesn’t matter. When you’re writing a Superman story, you’re not trying to find his toughest opponent, or his most difficult physical challenge. None of that stuff—super-speed, laser beams—matters at all. Instead, you’re trying to challenge the idea of morality.

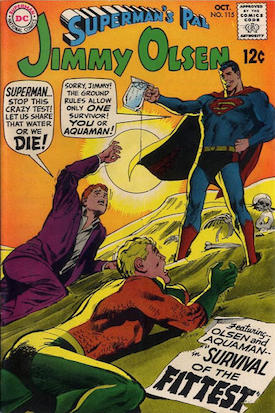

The greatest era of Superman comics were the books edited by Mort Weisinger in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s where most of the core Superman concepts came into being, and it’s where the greatest Superman comics of the modern age (the ones written by Alan Moore and Grant Morrison) found their inspiration. And if you read any Superman story from that time, you’ll find that very little of the plot has to do with Superman fighting anything.

Think about the strange ideas those comics delivered on a regular basis: Superman. Supergirl. Beppo the Super-Monkey. Bizarro Superman. Superman Red and Superman Blue. Superboy. Comet the Super-Horse. Streaky the Super-Cat. The Legion of Superheroes. You could easily argue that there were no characters in Superman comics aside from Superman himself; everyone else was a reflection of his psyche and an exploration of his themes. It’s as interior as a Beckett novel.

The over-literal interpretations of Superman that followed the Weisinger years are to blame for making Superman boring. The New 52 reboot of Superman has never been interesting. John Byrne’s sad attempts to create sci-fi justifications for Superman’s powers were about as fun as counting each individual piece of gravel in a driveway.

At least the much-reviled Death of Superman storyline, which many blamed for launching the comics bubble that almost destroyed the superhero industry in the 1990s, delivered four different Superman characters to comics, including a new Superboy and John Henry Irons, who was later known as Steel. The creators of those comics understood that Superman was only compelling when his basic goodness was reflected and distorted onto other personas.

So listen: Nobody cares about how much Superman can lift, or how hard he can punch, or whether he can beat Batman in a fistfight. The trick is this: think about the most decent person you can. Put pressure on that person. Imagine what would happen if that person happened to be, say, from the poorest one percent of the USA, or from a part of the world ruled by a tyrant, or raised by an Objectivist. What happens then? Is he still good? What if he’s in a situation where he has to confront a mistake he’s made? How does he behave then? What happens next?