The patron poets of Open Books

Sometimes when I’m feeling saucy, I’ll ask a bookstore owner to choose a book or two to represent their store. It’s a hard question to answer: how is it possible to reflect the character, staffing, and stock of an entire bookstore with a single book? It’s a question that has broken some booksellers; they shrug, or name a dozen books, or promise to get back to me and never do.

Perhaps when she takes over the store in August, new Open Books owner Billie Swift will have a different answer at the ready. Outgoing Open Books owner John Marshall, though, comes up with an answer almost immediately. He has three choices: Robert Sund’s Poems from Ish River County and Tacoma poet Laura Jensen’s books Memory and Shelter. Marshall never met Sund, but he says that “when people ask me for a poet who captures the Northwest,” his mind always turns first to Sund.

Sund, who passed away in 2001, was a poet, painter, translator and calligrapher. Ish River collects a large amount of his work into a single volume. Sund’s poems are short and very interested in the natural world, though he doesn’t fall into the traditional sense of naturalism: he’s not celebrating nature as an other, he’s observing it as a participant. Sund’s reflections on nature and his observations of people come from the same place: it’s a very Northwest-y approach to nature, a more holistic, modern understanding of humanity’s place in the universe.

“It’s surprising how many/people are laughing, once you get away/from universities/and stop reading newspapers,” Sund writes in a series of poems chronicling the life and work that centers around a grain elevator in eastern Washington. He’s pointedly not an academic; Sund is interested in work, and what work does to the world and to bodies. A student of Theodore Roethke, Sund’s writing continues a long Northwest tradition of labor writing.

The transitory nature of time figures into his work, too. “In America, history goes by quickly./Like a windstorm,” he writes in “My Father.” Later in Ish River he writes, “In the world of men/centuries go by leaving/little trace.” The things that will last are the rivers and the plants and the sun, he understands, but the sand-castle temporariness of present day doesn’t separate Sund from the people. Instead, it makes him want to celebrate the present even more. His poem “The Rest of the Way” makes plain this obligation to enjoy and capture the moment:

Our fathers

carried us

a long way into the world,

They leave us one day, and die.

And we carry them

the rest of the way.

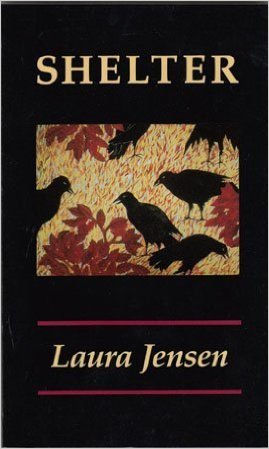

Jensen still publishes work occasionally, but Memory and Shelter are important to Open Books, Marshall says, because they were originally published by “a press in Port Townsend called Dragon Gate.” As poetry presses sometimes do, Dragon Gate went out of business, and their copies of Memory and Shelter were going to be pulped, “so we bought every copy,” Marshall says. “I am quite relieved to own them and sell them at a reasonable price.” In fact, Open Books still sells them at cover price: Memory, which was published in 1982, sells for $5, and Shelter, which was published in 1987, is $7.

Jensen’s poems are not so specifically interested in the Northwest as Sund’s poems are, but they are very much of the Northwest. One poem imagines the Goodyear Blimp going AWOL. She stops mid-poem at one point to wonder what Anne Sexton is up to. She reflects on being terrified of The Creature from the Black Lagoon as a child, and how even now

I cannot turn from creaks

in the floor,

from cracks

in the table.

I keep my eyes open and have to see

if something is terribly wrong here.

Her poems are distinctly interested in seeking out the “terribly wrong.” Marshall calls Jensen’s poetry “delightfully strange.” She reflects on a beachside promenade in Oregon, imagining the waves of humanity coming and going—the youth charging forward into the water, the elderly standing back and watching the waves.

Jensen is not a Northwest poet in the same way that Sund is a Northwest poet. Jensen is more socially Northwest; her response to the world — that sense of being apart from humanity, even as you acknowledge your place in the throngs on the sidewalk — is very Northwestern. Sometimes, she is chilly and distant. Other times, she’s awkwardly close, her breath on your skin. But wherever she stands — be it inside your comfort zone or across the street, judging you harshly with a glare — Jensen is always saying something of interest.

You could put these two poets in a line — Sund on one end by the moss-covered tree trunks, Jensen on the other end, over by the sidewalk café where people sit out in the light rain pretending not to be bothered — and in between them, you could fit every Northwestern poet who writes or ever wrote or ever will write. In that way, they are the twin perfect patron saints of Open Books. They represent us all.