Thursday Comics Hangover: Dumbforgiven

My favorite writing podcast isn’t about poetry or novels or non-fiction. It’s about screenwriting. John August and Craig Mazin’s Scriptnotes is a long-running podcast that takes listener questions, offers industry interviews, and occasionally pulls screenplays apart to see how they work. While Mazin and August are sometimes a little too conventional in their advice — the film industry does love a formula — they’re great hosts who cheerfully provide useful information, and they’re terrific in the way they treat writing as a craft and not divine inspiration. Any writer could learn a lot from the way they discuss their jobs.

In their most recent episode — embedded above — August and Mazin discuss the script for the Clint Eastwood masterpiece Unforgiven. It’s one of their best episodes, because their obvious enthusiasm for the script shines through in every moment. They rightfully praise Unforgiven for its economy: every line in the script either advances the story or establishes theme and character, or (most likely) both. They discuss why the screenwriter, David Webb Peoples, made decisions that contradict every piece of advice you’ll read in screenwriting guides, and they debate decisions that Eastwood made as he translated the script to screen. I encourage any writer to listen to this podcast.

So. What does all this have to do with comics?

I’ve been thinking a lot about comics writer Mark Millar lately. Millar made news earlier this month when it was announced that he sold his creator-owned comics line, Millarworld, to Netflix in a development deal that has been rumored to be somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 million. Millar has been praised as “the Quentin Tarantino of comics,” likely because his books are generally full of “adult themes” like violence and swearing in a way that superficially resembles the aesthetic of Tarantino films.

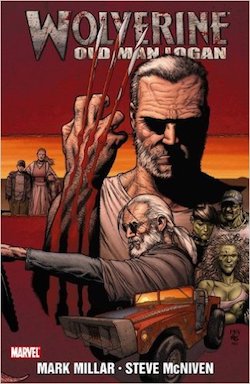

If you enjoyed the X-Men spinoff film Logan that was released in spring of this year, you probably know that it’s based on a Millar comic called Old Man Logan. Logan is far superior to Old Man Logan, in part because it’s handled with a maturity that continually escapes the comic. Millar’s Old Man Logan is a trashy joyride through a dystopian Marvel Comics future — one in which the Hulk fucks his own cousin, Spider-Man’s daughter is repeatedly ogled as jailbait, and the Red Skull dresses up in Captain America cosplay for cheap shocks.

At the time of its release, and repeatedly in years since, Old Man Logan has been sold to audiences as Unforgiven starring Wolverine. Superficially, that connection makes sense. Old Man Logan centers around an old man who was once a fearsome warrior but who hasn’t taken up arms in years. He’s reluctantly pushed back into his old life, and he’s eventually subsumed by the violence that swallowed his youth. In both stories, the hero is a threat, one that is teased from the very beginning of the story and only rolled out at the very end. It’s the same basic plot structure.

But listening to Mazin and August enthuse over what makes Unforgiven special really hammered home everything that’s terrible about Old Man Logan in specific, and Millar’s writing in general. Unforgiven is thematically about the stories we tell each other, and the distance between stories and reality. Old Man Logan is nothing more than a string of “cool” moments. It’s not about what it means to be a killer — Old Man Logan is a celebration of violence, written by someone who seems to think that Unforgiven exists so that Clint Eastwood can, in the end of the movie, shoot a bunch of people and look badass while he’s doing it.

And ultimately, that’s what all of Millar’s books are: bad misreadings of popular culture. His books build on premises that every 15-year-old comics nerd has idly wondered: What if Batman was actually the bad guy? What if Flash Gordon starred in Unforgiven? What if the bad guys killed all the superheroes? And then it does nothing more than revels in the “coolness” of the premise, providing a string of money shots that forcibly injects chills into the cerebral cortex of fanboys.

Of course, I suspect this off-brand hucksterism is not a bug for Netflix, but a feature. Comic book movies and shows based on Millar’s comics will appeal to the penny-pincher in all of us. They look enough like the real properties to be enticing to our basest instincts, and they’re stuffed full of enough violence and nasty thrills to keep us watching. And sometimes — as in Logan — talented filmmakers might be able to transform Millar's doggerel into verse.

As an investment, I'm sure Netflix feels pretty good about the content they bought. Unfortunately, Millar — who always reaches the most facile decisions — will only be emboldened by their purchase. He's just getting started.