Our sincerest thanks to Janine A. Southard for sponsoring The Seattle Review of Books this week.

In the hilarious, and well-loved Cracked! A Magic iPhone Story (four stars on Amazon!), the award-winning Southard (a Seattle denizen) shows you how the geeks of Seattle live, provides a running and often-hilarious social commentary on today’s world, and reminds you that, so long as you have friends, you are never alone.

Help support The Seattle Review of Books by reading her excerpt and ordering the novel if you like what you read.

The Sunday Post for August 2, 2015

(A collection of pieces we noted this week.)

The Last Days of Kathy Acker

Her books were also fever dreams of escape and reinvention, and Acker’s own forbidding physical appearance—she could look, alternately, like a deranged kewpie doll, a pirate from the future, an alien courtesan—embodied such transformations. She spent years turning her body, simultaneously a source of pain and possibility in her work and life, into a protective carapace.

Reverse Logic

An amazing story about Webster's editor Philip Gove, and how he used symbolic logic and other programming-esque tricks during the revising of Webster's dictionary, when it was time to update the famous 1934 second edition.

Structure was paramount to Gove. He was a linguist who used the logic of a programmer, and in the 1950s and ’60s he seems to have been thinking about the dictionary with the extreme rigor of a software engineer. Though he could never have imagined search as we know it today, he would have been among the first to intuit its uses for lexicographers. So as work on the Third was winding down he took another step to address a kind of question that only a computer could easily answer: he set the typing staff the new task of creating a 3”x5” slip for virtually every word that appeared in boldface in the dictionary typed backward, each letter followed by a space (and spelled normally, without the extra spaces, below its backward spelling).

A true digital recreation of Borges's Library of Babel

This one might take a month of Sundays to even start browsing. Borges’ Library of Babel is now real, on the internet, created by Jonathan Basile. In fact, we were able to find the phrase "the seattle review of books recommends this virtual reconstruction of borges library of babel"

From the About page:

libraryofbabel.info is now in its second iteration. When the project began, I thought that even a virtual universal library faced insurmountable limits that made its realization impossible. But with the help of some advice I received from friends and visitors to the first version of the site, I’m happy to say that I’ve proven myself wrong.

The library originally worked by randomly generating text documents, storing them on disk, and reading from them when visitors to the site made page requests. Searches worked by reading through the books one by one. It was a method with no hope of ever achieving the proportions of the library Borges envisioned; it would have required longer than the lifespan of our planet to create and more disk space than would fit in the knowable universe to store. I wrote about the cosmic proportions of this shortcoming in a former theory page.

Because the virtual world often inspires suspicion, I feel I should explain how the new library functions, to reassure anyone who might think some chicanery was at work. I would be the first to be disappointed if this site did not truly contain what it claims to: every possible page of 3200 characters. I encourage those who prefer a sense of mystery, rather than knowing what goes on behind the looking glass, not to read on.

Rahawa Haile’s short stories of the day, of the previous week

Every day, friend of the SRoB Rahawa Haile tweets a short story. She gave us permission to collect them every week.

And, this week, Kevin Nguyen interviewed her about the project in the Oyster Review. (it’s worth reading the whole thing for her last line, but this quote here is pretty choice, too).

I am highlighting a short story every day by authors who aren’t white men because “diversity matters” deserves to be more than sentiment. Because I want people to reevaluate whom, how, and why they read, especially when it comes to this art form. And it isn’t just the canon I have in my crosshairs: it’s a publishing industry that continues to favor white male authors, national newspapers that favor white male authors, a literary magazine tradition that favors white male authors, and MFAs whose graduates, as recently as five years ago, were 72.8% white.

Short Story of the Day #206

Prathna Lor's "Secret Potato Chip Dialogue Over the Phone" (2009)

http://t.co/UcoUDtVeL6 pic.twitter.com/GJXKxzowj4

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 26, 2015Short Story of the Day #207

There is love in you. pic.twitter.com/J5slGY03X5

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 27, 2015Short Story of the Day #208

Jessica Afshar's "The Lake"

Sou'wester (2012)

http://t.co/647sQXWlSl pic.twitter.com/KDP5YXM3ON

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 28, 2015Short Story of the Day #209

Sara Vogan's "Sunday's No Name Band" (1984) pic.twitter.com/58iWSCiJYR

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 29, 2015Short Story of the Day #210

Rumaan Alam's (@Rumaan) "Even the Fox"

Juked (2013)

http://t.co/8lo2kuj47P pic.twitter.com/qZjKMoU6uT

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 30, 2015Short Story of the Day #211

Chantal Clarke's "My Life"

n+1 (2015)

https://t.co/UiaPMIZU2k pic.twitter.com/wmKDTYHM94

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 31, 2015Short Story of the Day #212

Black girls, you can do anything and go anywhere. Don't let them tell you otherwise. 💁🏾⛺️ pic.twitter.com/a6cQrXzQov

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 31, 2015People! Ask yourselves questions about your assumptions before you make best-of lists. Something like this, from Time magazine, is no longer acceptable in 2015:

.@TIME's best books of the year so far is 100% white: http://t.co/kllUcxQtoP

— Amanda Nelson (@ImAmandaNelson) July 31, 2015Either Time is arguing that no person of color produced an amazing book this year, or they're admitting that they're only interested in books by white people. Neither option is good.

At the very least, this is a fine opportunity to remind you to check out the #weneeddiversebooks hashtag on Twitter, where we're reminded that good books are being published all around us. It's our responsibility to find them — especially for those of us who happen to work in the media.

Over at Book Riot, Angel Cruz discusses how the American Girl series of books helped her embrace her own history, though many may "wonder how a nerdy Filipina girl feels kinship with a Victorian-era heiress."

The Help Desk: Introducing our new literary advice column

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid will offer solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My boyfriend and I are moving in together next week. I'm very excited about this, and I'm confident it's the right move. But we just had our first fight over a moving issue, and it's something I feel very strongly about: he wants to merge our book collections together. I want to keep our shelves separate. It's not that I fear intimacy; I'm 95 percent sure we're going to get married one day, and I'm very happy with him. But I'm not sure I ever want our books to mingle. Is a lifetime of bookshelf non-monogamy too much to demand?

Judy from Ballard

Dear Judy,

I have never lived with a man — not because I refuse to blend my bookshelf, for far more broken reasons — so feel free to take my advice with the same side-eyed respect you’d give a porn star in sweatpants. As I see it, how you arrange your book collection is a sacred thing. For instance, my books are arranged on three shelves: The top is all-time favorites no one is allowed to touch; the second is books I have never read, arranged in the order I aspire to read them; the third is books I have stolen from other people, mostly for petty reasons.

If a MAN came into my space, swinging his DICK around and inserting copies of How to Win Friends and Influence People and Atlas Shrugged and Hemp: A History all willy nilly — trigger warning — my shelves and I would feel a little violated.

Explain this to your boyfriend. If he still does not understand the importance of separate bookshelves, I suggest you get a cat. Name it Cienna. Then, whenever you and your boyfriend have a domestic dispute, wait until he sleeps. Take one of his books off the shelf. Piss on it. Blame it on Cienna. This will provide you with a physical way to vent your spleen after a fight (full disclosure: I don’t know physics) while slowly weeding your bookshelf of his books.

You’re welcome,

Cienna

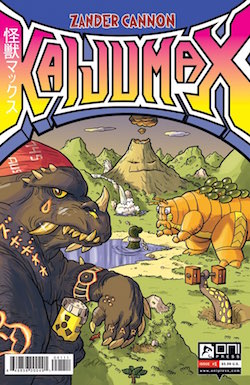

Thursday Comics Hangover: Kaijumax loses its balance

(Every comics fan knows that Wednesday is new comics day, the glorious time of the week when brand-new comics arrive at shops around the country. Thursday Comics Hangover is a weekly column reviewing some of the books I pick up at Phoenix Comics and Games, my friendly neighborhood comic book store.)

“We should not be tolerating rape in prison, and we shouldn’t be making jokes about it in our popular culture,” President Obama announced in a speech about criminal justice reform earlier this month, adding, “that is no joke. These things are unacceptable.”

He’s right, of course. In addition to being simultaneously cruel and facile, prison rape jokes are one of the last safe spaces for homophobia in popular comedy. And still, most comedies about prison or crime include at least one prison rape joke. What does it say about us as a society — especially a society with the largest prison population in global history — that we’re okay with this?

And what does all this have to do with comic books?

I’ve been reading and enjoying Zander Cannon’s new comic from Oni Press, Kaijumax, an ongoing series about giant, Godzilla-style monsters thrown into prison for trying to destroy cities. The “prison” is an idyllic island far from civilization, and the guards are Ultraman-like humans. The book demonstrates a bone-deep understanding of kaiju cliche and is packed with little in-jokes for people who’ve spent way too many hours of their lives watching adults in rubber lizard suits destroy cardboard cities.

But the kicker is that the kaiju all act recognizably human. These are monsters that worry about their families back home. They try to talk to the guards about life. They have regrets. The absurd premise smacks into the silly drawing style and the convincingly portrayed emotions, and the reader isn’t quite sure how to land at the end of each issue. It’s a pleasant kind of discombobulation.

But the latest issue of Kaijumax, issue #4, opens with a sequence that throws the story’s balance off-kilter. One of the kaiju, the buglike Electrogor, is bathing in a waterfall. Another kaiju, a lizard-looking monster with a scorpion tail named Zonn, approaches him and starts talking. Soon, Zonn is holding the struggling Electrogor down and piercing his carapace with his tail-stinger. The scene plays way too close to the reality of prison rape, and it flat-out ruins Cannon’s juggling act.

To Cannon’s credit, he doesn’t play the scene for laughs. And he shows the aftereffects of violence: Electrogor suffers from the violence for the rest of the issue. He’s delivered, crying and vomiting, to the island’s hospital where he tells the nurse, “T-terrible thing happened me.” This isn’t a Chris Tucker punchline tossed into the end of a buddy cop movie. But is it necessary?

In the letter column of this issue of Kaijumax, Cannon addresses the scene head-on. When a reader writes in to say that “the rape-ish jokes and pretend-[racial] slurs make me uncomfortable and I think there’s kind of a disconnect between the more cutesy art-style and pretty serious subject matter. Is this uncomfort [sic] and stylistic disconnect intentional or am I just too sensitive you think[?]”

Cannon replies,

I do intend there to be a bit of an uncomfortable edge to it. My hope is that it’s not too off-putting; I want the mismatch between the prison harshness and the monster-ridiculousness to be humorous, not mean-spirited. I acknowledge that I’m walking an edge with some of the call-outs to racism and sexual assault, but the book will always stay more or less in the PG realm; everything has a monster-movie equivalent. Hopefully the vague sense of unease it gives you now will be as bad as it gets. This issue is the one that I was (am?) worried about being slightly over-the-top in terms of what it was about, but I’m too close to it to know if it crosses the line. I don’t think so, since the nature of Electrogor’s assault is firmly in the monster-movie realm and veers very wide of what I expect would upset someone. All that being said, of course, not every comic is for everyone.

Clearly he’s put a lot of thought into this, but as a reader, I think Cannon is wrong; in this case, the scene plays out too closely to the kind of scenes we see on TV and in movies on a regular basis. By relying on the shorthand that entertainers have used for decades — the shower scene has played out hundreds of times in hundreds of ways — Cannon becomes a participant in a long and shameful tradition, even as he tries to transcend it.

The excellent local literary magazine The James Franco Review, which has a blind submission policy intended to "publish works of prose and poetry as if we were all James Franco, as if our work was already worthy of an editor’s attention," published an editorial today that all white editors — ourselves included! — should read and take to heart.

The editors behind the excellent 33 1/3 series of books about albums have published all the information collected during their recent open submission process. It's a fascinating look at why the new-arrivals tables at your local bookstore are still dominated by books by and about men.

Of 605 book proposals received, 18.3 percent were written by female authors and 81.7 percent were by male authors. Not even twenty percent of submissions were from women! That's horrendous. Even worse is the gender split of the musicians these writers want to write about: 11.3 percent of all these pitches were about female artists, and 8.7 percent were for mixed-gender or undefined acts. The remaining 80 percent of submissions were about dudes.

We should be grateful to 33 1/3 for being so transparent about all this. It's another damning mound of data we can add to the work Nicola Griffith has been doing to unveil the publishing industry's institutional sexism. If you haven't already, you should read Griffith's explanation of how we can help women's voices be heard in literature. It's up to all of us to make a change.

Updated (12:32 PM) to add that if you want to read a great discussion about gender in publishing, you should visit this Metafilter thread about our discussion with Nicola Griffith. There are some great voices and experiences in the thread, and you should go contribute. (For real — if Reddit has scared you away from online community conversation, this MetaFilter thread will restore your faith in online humanity.) We're really excited to see these conversations take off.

Short Run, the great small-press festival that local author Kelly Froh co-founded, is running a comics summer school every Monday night in August, with classes including how to computerize your art, screen printing, inking, watercolor, and drawing perspective. Each class is very affordable (Short Run is charging anywhere on a sliding scale from five to 20 dollars per class) and hosted by local cartooning greats including Eroyn Franklin, Robyn Jordan, and Max Clotfelter. If comics are your thing, you should sign up for at least one of these.

So, a little news. We are shuttering PANK in December '15. It has been a great decade. 1 more print issue, 2 online between now/then.

— roxane gay (@rgay) July 29, 2015Literary Twitter — Lit-ter? — is at the moment (and rightfully) more than a little upset about the news that literary magazine PANK is going away.

Friend of SRoB Rahawa Haile puts it best:

I mean do y'all know how many lit mags have black women as publishers? I just. I'm gonna need a minute. This was always gonna hurt.

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) July 30, 2015Literary magazines, for the most part, are short-lived creatures. They're born, they live within a certain time, and they're gone. The amount of surprise and shock PANK's shuttering has inspired is telling: we all thought that somehow, against all odds, it would last forever.

Seattle writing prompt #1

Ask any writer: the two most difficult parts of the writing process are 1) sitting down in the seat to write and 2) figuring out what to write about. We can't help you focus on your work, but we can try to help you find inspiration in the city around you. That's what Seattle Writing Prompts is all about. These prompts are offered free to anyone who needs them; all the Seattle Review of Books asks in return is that you thank us in the acknowledgements when you turn it into a book.

The opening paragraphs of this Seattle PI story by Daniel DeMay are so vivid and intriguing that they're practically the beginning of their own sci-fi novel:

Imagine a greater Seattle area that is clearly thought out, directed and completely planned for.

Rapid, subway transit lines connect east to west, north to south and neighborhoods across the city. An above-ground rail line links Everett to Tacoma and passes through a central station where Roy Street now intersects with Highway 99.

Downtown buildings are capped in height, much like Paris, so as to let light into downtown streets. Mercer Island is one big park, restricted from development. And city government offices are condensed in a grand civic center across Denny Way from where Seattle Center now sits.

All this and more was envisioned by Virgil G. Bogue, an engineer and -- some might say -- visionary who came to draft a sweeping plan for Seattle in 1911.

Go read the whole great story to find out why we're not living in Bogue's Seattle. And then think about what would have happened if Seattle voted for Bogue's plan in 1912. What do you think everyday life would be like 100 years later in that Seattle? Would it be an urbanist utopia, or an antique-looking steampunk wasteland? Take a walk and try to overlay Bogue's vision on top of the city you see. Then write about it. Let us know if you come up with something interesting.

Piper Daniels interviews excellent local poet Maged Zaher over at the Monarch Review about race, Seattle, and street harassment. It's a must-read. Zaher is more than just one of the best poets in Seattle; he's also one of our most fearless political voices.

Sometimes you do the job and sometimes the job does you

Published July 29, 2015, at 9:49am

Seattle cartoonist Kelly Froh's "Tales from Amazon" minicomics are friendly like a handwritten letter, but they're all about bad behavior in the workplace.

The Man Booker Prize announced their longlist this morning. The criteria changed last year to be open to international authors writing in English; up until last year, it was solely a prize for writers from the UK commonwealth, Ireland, and Zimbabwe. The longlist is:

Bill Clegg (US) - Did You Ever Have a Family

Anne Enright (Ireland) - The Green Road

Marlon James (Jamaica) - A Brief History of Seven Killings

Laila Lalami (US) - The Moor's Account

Tom McCarthy (UK) - Satin Island

Chigozie Obioma (Nigeria) - The Fishermen

Andrew O’Hagan (UK) - The Illuminations

Marilynne Robinson (US) - Lila

Anuradha Roy (India) - Sleeping on Jupiter

Sunjeev Sahota (UK) - The Year of the Runaways

Anna Smaill (New Zealand) - The Chimes

Anne Tyler (US) - A Spool of Blue Thread

Hanya Yanagihara (US) - A Little Life

The shortlist of six authors will be announced on September 15th, and the winner will be announced on October 13th.

Literary awards are fun, silly things. They don't make a book any better or worse, but they do generally help get books in the hands of more readers, which is always a good thing. The Seattle Review of Books is rooting for Laila Lalami.

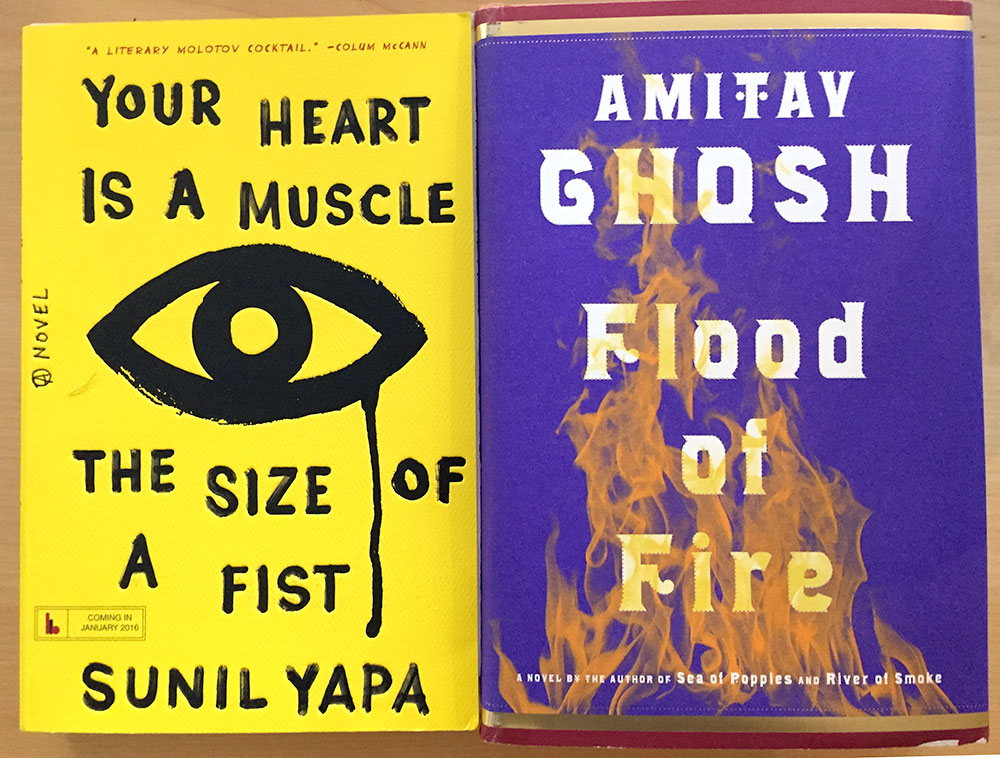

Mail call for July 28, 2015

Okay, a confession: we literally squeed when we saw the Ghosh book. The Ibis Trilogy has been that good, so far.

The New Statesman interview with sci-fi great Michael Moorcock is absolutely worth reading, if just for all the punches thrown. Some quoteworthy moments:

Who really cares about spaceships and how rockets work? I don’t actually care about space at all. You had to plough through all this shit that people like Arthur [C Clarke] insisted on expositing to get to maybe five good images.

and

We live in a Philip K Dick world now. The technology-led, military-led big names like Asimov, Robert Heinlein and Arthur got it dead wrong. They were all strong on the military as subject matter, on space wars, rational futures – essentially, fascist futures – and none of these things really matters today. It’s Dick and people like Frederik Pohl and Alfred Bester who were incredibly successful in predicting the future, because they were interested in social change, ecology, advertising. Look at Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Google . . . These are Philip K Dick phenomena.

and

I was attracted to both rock’n’roll and science fiction because you didn’t know what was going to come out at the end

and

“I think [Tolkien]’s a crypto-fascist,” says Moorcock, laughing. “In Tolkien, everyone’s in their place and happy to be there. We go there and back, to where we started. There’s no escape, nothing will ever change and nobody will ever break out of this well-ordered world."

Oh, hell, just read the whole thing. Few things in this world are as beautiful as an old sci-fi novelist who doesn't care what anyone thinks anymore.

A few comments on comments

The Daily Dot's Austin Powell and Nicholas White explain why the site is doing away with its comments section:

The general consensus is that we need to detoxify the Web—to make it a cleaner, nicer, safer, and more inclusive place to live and work. Of course, at the Daily Dot, we would like to see a more civil, compassionate Web, but we want to be careful that in the name of fostering civility, we do not inadvertently kill all dissention. It is the cacophony of the Web—the voices from every point in the spectrum that give it its vibrancy—that make it the community we love. No one has quite figured out how to thread that needle yet, even those who have invested significantly in their own internal systems.

So it's time to get a little meta: you may have noticed that the Seattle Review of Books does not have a comment section. This isn't because we don't care what you have to say. On the contrary, we're big believers in the fact that this is a community site, and we want our readers to feel ownership in Seattle's greater literary conversation.

But the fact is that a comments section needs to be groomed and maintained, just like any other part of a website, and between our day jobs and behind-the-scenes site work and — oh, yeah — reading books, we just don't have the time to grow the comments section we'd want for the site. An uncultivated comments section is rarely a useful thing; studies have shown that a bad comment section at the end of an article can ruin a reading experience. And we are all about good reading experiences here.

Plus, it seems silly to half-ass a comments section when other web providers supply excellent comment sections where everybody is already talking all the time: Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and so on. And if you're having a conversation out there, you should definitely include the Seattle Review of Books. We're on Twitter and Facebook and you can contact us via email anytime. We're excited to talk with you and to take part in the ongoing conversation that is Seatle's literary scene. We hope you'll reach out any time through any number of avenues. We look forward to many years of comments and discussion.

KING 5 is reporting that local true crime writer Ann Rule has died. If you've never read The Stranger Beside Me, about Rule's personal relationship with serial killer Ted Bundy, you really should. It's far and away her best book, and a classic of the true crime genre.

I wrote a snarky overview of Rule's writing back when I was the new kid at The Stranger, and while I regret the tone of the piece — I was so much younger then! — I do not regret my opinion of Rule's work. Her writing was often a little florid, but she was an impeccable journalist, an expert interviewer, and a terrific researcher. She deserved better from me than the piece I delivered, and I'm not going to link to it here.

Rule demonstrated exactly how reporters should cover crime: with facts, with hundreds of pages of research backing you up, and with a ton of compassion for the victims and survivors of the crime. She never sold a victim out in exchange for a great story. She always listened to survivors, and gave them time and space to tell their stories. There aren't enough reporters like her left anymore. It's so sad that Rule's last days were so difficult. She deserved better from the world after such a singular career and such an impressive body of work.

Talking with Nicola Griffith about the importance of counting women's stories

(Nicola Griffith, best-known as the local author of Hild, published an astonishing blog post in late May of this year. Titled “Books about women don’t win big awards: some data,” Griffith presented a number of striking charts demonstrating the gender split between winners of awards like the Pulitzer Prize, the Man Booker, the National Book Award, and the Newbery Medal over the last 15 years. Unsurprisingly, more men than women have won almost all of those awards. But then Griffith noted an especially interesting statistic: the women who do win awards tend to win for books about male main characters. The post went viral. One week later, Griffith asked other people to take up her charge, to help count women’s voices in literature:

So, we need data. This is where you come in. We need many people counting many things. The more who count, the less each of us has to do.

Last week, Griffith spoke with the Seattle Review of Books about her findings, the status of the project, and what all this damning data means for the state of the publishing industry.)

Thanks so much for making the time for us. First, I wanted to talk about how you came to decide to quantify this gender divide in a way that, to my knowledge, had never been done before.

It’s a whole bunch of coming-together of circumstances. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for years — I definitely was talking about it in the early 2000s. I remember doing a blog post called “Girl Cooties,” which was basically about this issue. I’d done a rough [gender] count, but I hadn’t done the graphs. People listened, but it didn’t really go anywhere; everybody kind of knows it’s true, but they don’t want to see it.

My book Hild was out here in paperback and it came out in the UK in hardcover, so I had to do publicity — write “five-best” lists and, you know, that kind of thing. So I was thinking about my five favorite historical novels and I wrote them down and I was pleased because at least three of them, or actually four of them, were by women. I thought, “yay women!” And then I realized that those books by women were all about men. And then I thought, “goddamn.” These were my influences.

And at that point, my wife was working — still is working — downtown at an SEO-based tech company. She was having to rejigger how she presented her material to them, and so she started doing a lot of charts. And so I looked at the charts one day, and I thought to myself, “you know what? I could do this in charts.” So it was just a whole bunch of circumstances coming together.

So I just had to pick some awards and figure out how to do this on free software and make it pretty and brightly colored; and more to the point, I needed colors that would make sense instantly. So I just figured it out and did it and thought, I’m not going to editorialize. I’m just going to put the data up there and let the data speak for themselves. And — boom — the world went mad. I was quite astonished, actually.

Did you get pushback at the time?

I got zero pushback. The only pushback I kept getting from people was, “Olive Kitteridge won the Pulitzer and that’s about a woman.” Ah, well, no. It’s a bunch of stories connected and the first one is actually from the point of view of a boy, so I counted it as both — you’ll see in the data, I put a footnote in for it. But that’s the only serious pushback I got. I’ve seen other people’s blogs who reblogged my stuff and people haven’t been so kind to them. But I’ve been very lucky, I think.

Have people volunteered to help you with the project?

I had a lot of volunteers, and I find myself reluctant to actually take charge of them. Not because I dislike taking charge. I do, and that’s my problem. I’ve taken charge of many projects in my life and I don’t want to carry the torch on this one. This is something I want to be a distributed effort. I want many people all over the world to do their own thing, to put their results on their platforms, and to talk about it to their people.

And at the same time, I recognize there has to be a point where people can go to. Like VIDA — they are now the recognized counters of this stuff. In a perfect world, I would find a university department or an organization that would be willing to take this on. But you know, I have many jobs already.

The tools are really cheap these days. You can do Google documents, you can do all kinds of chart-making, you can make a website for essentially no money. It just takes time to organize it, and I don’t have that. So really, my call to people now is: please, somebody else, take this burden from me. I will of course keep talking about it, I’ll keep posting the occasional thing, but I’m a novelist. I write, I don’t organize massive groups of people. I have done that before, and it’s not my favorite thing.

Do you think, for instance, that Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch would have earned as many accolades had it been about a female protagonist? Are authors pressured to write about men?

That’s difficult to say, because I actually couldn’t read The Goldfinch. I read the first few pages and I really hated the way she handled it, and I just couldn’t read the book. I had a lot of people who read it tell me it’s a great book. It’s not my kind of book.

But I was reading — not the most recent Paris Review, but the one before — and there was an interview with Hilary Mantel. I don’t have the exact quote handy, but she said something like the first book or two she wrote, there were no women in them because she didn’t think women were interesting. They didn’t matter. And then she went back to rewrite [her historical novel about the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety] and thought, “I have to fix that.”

I don’t think it’s industry pressure, I think it’s the way we’re brought up. Would Donna Tartt have won if she had written about a girl instead of a boy who becomes a man? I suspect not, but that’s just a speculative thing. I really couldn’t say.

I still remember this screenwriting course I took in high school. A friend of mine wrote her screenplay about a male protagonist and our teacher, who was a man, kind of pressured her in front of the class, asking her why she wouldn’t write about a woman. His heart, I think, was in the right place. He wanted women to have the agency to write about women, but the way he presented it was kind of a shaming moment. Do you have any advice for people who want to talk to women about their protagonists?

I think it really depends on the tone of the comment. If it’s “you should write about girls because you’re a girl, so stick to what you know, sweetie,” if it’s a belittling comment, then that demands one kind of response. But if it’s worded, “the world needs more stories about women. Do you have any ideas about women?” That’s a really different comment.

I would say, if someone says, “stick to your own little box, sweetie,” then you get up in their face and say “fuck you and the horse you rode in on. No.” And if someone says kindly, “wow, so why are you writing about a boy here? Have you considered gender-swapping and see what happens?” That’s a really different kind of comment, I think.

Do you ever find you have to edit the institutional sexism from your work?

I never had to up until I wrote my most recent novel, Hild, which is set 1400 years ago. Then all this stuff clicked into my head — how I thought I knew women were back in the day, and what women’s roles were back then. And I believe that I took the received wisdom as gospel. I had to think my way out of that particular paper bag, I had to think hard. I didn’t want to write a whole book about a woman being badly treated and being forced to have babies and doing a lot of weaving. I just didn’t want to do that. I had to figure out how I could make a woman be a person with agency back in the day.

And it turns out that women have always had agency. We’ve always been real human beings. It took a lot of work, it took a lot of fighting through my own layers of — hmm — indoctrination, I suppose.

Once I had figured that out, I realized how many dykes — especially English ones — are now writing historical fiction. Jeanette Winterson, Stella Duffy, obviously Sarah Waters. All these people are just writing about the past and I don’t know how aware of it they are, but I have become super-aware of basically rewriting the past and reclaiming it and just saying, “okay, it was possible for women then, it’s possible for women now. It will be even more possible for women in the future.”

It’s my way of changing the world, I suppose, one reader at a time.

You've said that one of your goals as a writer is to run your software on other people's hardware. I've called books the greatest engines of empathy humanity has ever created. But if this is true, why aren't books more progressive about gender inclusivity than other media?

Because of the books that have gone before. Because this is how we are brought up. Because of the books we have read — all those wonderful writers. When I was coming up with my list of five historical novels, the books that actually influenced me as a writer, it was Mary Renault, it was Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave. They were all about men, famous men.

My favorite books are always widescreen epical things, sagas where people whack other people’s heads off with swords. Very nicely written, with lots of sensory detail. People grow and change, et cetera et cetera. People don’t seem to write books like that about women. And that pissed me off.

So I think we don’t because we haven’t. Books don’t because books haven’t. It’s a chicken-and-the-egg thing. And I do think we’re breaking that particular egg, and what’s going to come out isn’t a chicken. It’s a swan. It’s emerging kind of tentatively.

I can speak to me as a prime example because I’m the example I know best. I don’t think there is another book like Hild right now. It’s about a woman who was strong 1400 years ago as a woman, but it has lots of epical stuff. It’s not about using the power of sex to get your own way. It’s not about using her womanhood to achieve things. She is achieving things as a person, with her mind, with her actions. She does have some sex, obviously, and it’s great sex. But that’s not how she achieves her power.

You mentioned gender-swapping before, but that’s not the answer, either, is it? There almost needs to be a whole different vocabulary, a bottom-up reimagining of what a novel can be to accommodate strong female main characters. It’s not just a matter of doing a find-and-replace, “he” for “she,” is it? It seems like this requires a systematic rebuilding of fiction, and not just gender-swapping.

I think of that as “worm turns” fiction, where the people who have been oppressed suddenly have the upper hand. It’s like colorblind casting, in the 60s. I think that helped people understand that people of color are real people. Obviously, people of color knew that, but it’s still great to see yourself on stage that way.

It’s like that for women. We need to see ourselves as people, and if it takes just simple gender-swapping to start with to get yourself into that headspace, then great — use that as a tool. I think it’s a beginner tool, I think it’s a simplistic tool, but it might be an important one. It might be a big first step for some people.

A friend who works in publishing and I were talking the other day about how the publishing industry, anecdotally, seems to be made up primarily of women. She said that at most one out of every ten intern applications is a man, for instance. Her office is entirely women, except for the publisher, who is a man. But though women make up such a huge portion of the jobs in the industry, the seasonal catalogs I see are still vastly (and quantifiably) full of books written by and about men. Why hasn't this changed over the years? Why is it that women run the publishing industry, but they’re still not in charge of the publishing industry?

I think you’ve put your finger on it. It’s made up of women but it’s not run by women. It’s like nursing. If you look at hospitals, most of the nurses are women and most of the top administrators are men. It’s just kind of how power works. It’s an institutional thing. I don’t believe individuals are prejudiced, but the system is. Which is why I want data at every level.

Right at the beginning, as writers, what do we choose to write about? As I say, I think a lot of our influences are male writers and male protagonists. It’s easier to fall into that. So there’s that level.

Then you submit to an agent, you submit to a publisher, you’re accepted for publication. Are you going to be supported leading up to publication? At what level are you going to be supported after publication? Then there’s the buyers at the bookstores. And at every level, everyone falls back on what they know, or what they believe to be true. The way we’re brought up is that stories about men are important and stories about women are fluffy and domestic and kind of boring.

I don’t think it has anything to do with any of the individuals. That’s one of the reasons I wanted data. It’s about the system. It’s not about each individual making choices, it’s about what the system has done to their choices. It’s a very difficult thing to combat. I think the only way to combat it is to get every single person to pay attention, to literally count, to show themselves how they’re thinking.

Look at your own bookshelves. Count how many books are A) by women and B) about women. Look at your library. See how many books in prominent places are about women and how many are about men. Look at the new fiction table, how many are about or by women or men. And go on through every level.

If you’re in publishing, look at what’s submitted to you, and look at what you accept. If you’re a reader, look at what your friends are reading and talking about. And then count it, actually make a count over — I don’t know, however long works for you, whether we’re talking three weeks, three months, or a year. Whatever your focal length is. And actually look at your own data and then talk to others about it. I actually think people would be quite surprised at what they read.

I always forget the name of the experiment, but there is a lot of data that shows if you get 10 people in a room — especially in a traditionally male occupation like surgeons or police officers — and three of them are women, people will say it’s 50 percent women. Our perceptions are geared that way. It’s important to actually count. It’s one of the reasons I actually did this counting and the graphical representation of it. You can’t dodge the picture. It just lays it all out. There’s no way to argue with the data.