A rainbow of grief

If you hold a copy of Tom Hart’s new graphic novel Rosalie Lightning away from you by the spine, here is what you’ll see:

The pages are stratified in asymmetrical bands of black and white — thick stretches of white broken up by occasional, quick bursts of black, with one dense stand of black pages. You see this kind of striation in black-and-white comics collections all the time, but in Rosalie Lightning, it looks more portentous.

Hart’s daughter with fellow cartoonist Leela Corman, Rosalie — a seemingly healthy child — died in her sleep for no apparent reason just shy of her second birthday. Rosalie Lightning tells the story of what happened next, the first few hours and days and weeks after Rosalie’s death. Taken in that context, the bands of white and black start to make a horrible sense: anyone who has felt grief knows that the time immediately following a death is like that — everything has the color sapped from it, and the days and nights melt together as time begins to come unmoored. Some nights feel like thirty years, some days pass before you can successfully draw a single breath.

As an object, Rosalie Lightning promises that kind of a visceral journey through loss just by looking at the closed book. No matter where you are in the narrative, you know you’re always only a few pages away from the next dark patch. You never know how long the light will last, or when the darkness will come, or how long it will stay. In that way, it’s a lot like life.

Hart immediately immerses the readers of Rosalie Lightning into his child’s language. “Dideo atune” is Rosalie’s shorthand for “Totoro acorn” — a reference to the movie My Neighbor Totoro. “Mo mo mop” means “more more milk.” “Bath chicken” is “Buster Keaton,” “bumbites” are “bug bites,” “spidoo wam” means “spider web.” The words at first are introduced carefully and clearly, but after a while, Hart begins sprinkling them in the story and they become familiar as the reader acclimates to the toddler’s vocabulary.

This is not an attempt to pierce the hearts of readers with sentimentality. It’s a reminder that at one point in our lives, all of us are fumbling with the precision of words, that we are born in a place where words are meaningless — and if we live long enough most of us return there, too. We’re immersed in language in every moment of every day, but Rosalie is about the failure of words. While driving past a wintry field, Corman remarks on a cantering horse, which Hart mishears as “cantoring,” or singing. Even inches apart, and while observing the exact same scene, two adults can’t hear each other correctly. How can they possibly be expected to communicate and discuss the grief that they’re carrying? Can any language bear that kind of weight?

Probably not, but Hart is not just dealing with language; he’s a cartoonist, and that gives him an entirely separate vocabulary with which to communicate. Rosalie Lightning is illustrated in a scratchy style; you can practically hear the nib digging into the drawing board, leaving a rich black smear in its wake. Sometimes Hart draws his characters as rounded cartoons, like something out of a kids’ comic. At other times, he renders faces with an spray of jagged lines, to better portray the hurt hiding behind them. Other pages, the dark bands you can spot from the outside of the book, are drenched entirely in black ink. Those are the hardest days, the times when words fail him the most.

Until now, Hart was likely best known for one of his earliest comics, Hutch Owen’s Working Hard. The title character, an idealistic man who refused to sell out in an increasingly corporatized world, perhaps best exemplified the mid-1990s. With Hart’s messy-but-approachable artwork, the comic felt like a Nirvana song, photocopied and stapled down the middle. You could stare into Hart’s furious scribbles for hours and find new meaning in them every few minutes. Was he making fun of Hutch Owen or advocating for him? Did Hart want to flee society the way Owen did? What would Owen think of the world of 2016, where bands openly celebrate their songs being placed in commercials and people describe writing as “content” and urge individuals to advocate for their own brands? (And yes, I am aware that Hart published an ill-advised sequel a few years after Working Hard’s publication; the less said of it, the better.)

Working Hard achieved the kind of popularity that nowadays would be referred to as “viral.” Alternative comics fans loved it because the book was a throbbing love letter to uncompromised passion, and Hart’s scratchy style looked like literally nobody else’s. Cartoonists loved it because Hutch Owen’s refusal to sell out inspired them, reminded them that they were in cartooning for the art of it, not the commerce of it. (Not that this ever amounted to much of a dilemma; in those days, before graphic novel sections became the highest-profit shelves in bookstores, there weren’t many opportunities for cartoonists to sell out, in any case.) From 1994 to 1996, Hart was perched atop the cartooning zeitgeist, the one everyone was watching to see what he’d do next.

But Hart has not been very high-profile since his first major work became an alternative comics manifesto. He published an excellent graphic novel titled Banks/Eubanks, about an embittered old failed Owen-type who, distraught over the death of his dog, takes a trip to a paradisiacal beach that is just hunkering down in preparation for a huge and potentially cataclysmic hurricane. Banks/Eubanks was at once ambitious and restrained, a more literary cousin to Working Hard. That was 1999. I saw very little from Hart in the intervening years, but I never forgot what those early works felt like to his young readers: a shock to the system, a vibrant voice as energetic and potent as those first few chords you hear on a radio station somewhere, the kind of clear-eyed moment when you think to yourself, before the chorus even kicks in, “well, I guess I’ve got a new favorite band now.”

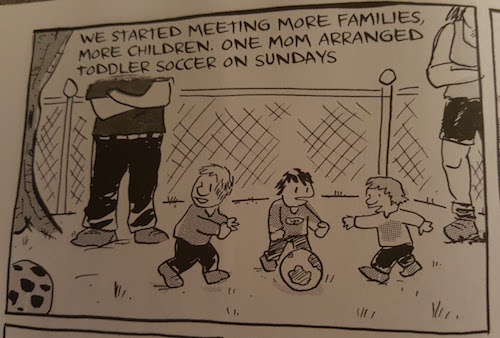

While Hart has shied away from major releases, Rosalie Lightning makes it clear that he never stopped cartooning in the decades since Working Hard. His style still looks primitive to the untrained eye — Hart’s faces are almost never composed of more than six lines — but anything more than a cursory glance reveals that he knows exactly what he’s doing. In one panel, three children play soccer while adults look on, and the amount of craftsmanship in that panel is almost too much for the eye to take in.

First, you have the body language, the headless parents hovering, bored, over the kids, arms crossed, shifting their weight from leg to leg. Then you have the kids: one boy distracted by a soccer ball downfield as a child with the ball prepares for another toddler lumbering forward to take it away from him. You have the chain link fence, the grass, the tree. Between the landscaped yard with its fencing and the adults standing sentinel over them, Hart is suggesting, these three kids are safe to live out their game. Nothing can possibly harm them, except for each other. And even then, if, say, the toddler with the ball gets kicked in the shin during a wobbly attempt to steal the ball from him, you know he’ll be scooped up in the arms of a nearby parent in a matter of seconds. No injury will befall them. They are surrounded and safe.

Except.

Except safety is an illusion and heartbreak can descend at any moment. Rosalie Lightning jumps forward and backward in time, around Rosalie’s death. At one point near the middle of the book, Hart tries to center on his loss and he can’t quite do it. He remembers the funeral, which he envisions as a bunch of adult’s legs standing around a tiny shrine made of Rosalie’s favorite books and objects. Then, in a completely black panel, he tries to recall “the hospital,” but then he interrupts himself, “No — I don’t like that part.” Then, in a blurry panel, he recalls “the paramedics,” which is a swirl of ink and some lines through which the reader can barely make out two figures standing over a figure that could — barely — be recognized as Rosalie. Having failed to step back into those uncomfortable memories, the next panel is Hart holding a bleary-eyed Rosalie with the caption “waking up in the morning.” It’s easier for him to remember her alive, and so he does.

Rosalie Lightning is many stories at once. It’s about Hart’s decision to leave New York City, which he depicts as a gigantic, bloodshot-eyed rat, with cars driving up its ropy tail and billboards for The Gap piercing its mangy fur. He and Corman are sick of barely getting by; they’re desperate to find some other place where they can live and draw and be a family. It’s about Hart’s quest for the authentic in an increasingly inauthentic world. It’s about his restless movements in an attempt to find community, even though all he sees in other people is the memory of his lost child.

It’s preposterous to talk about healing in the face of a loss like this. This book is cracked open by Rosalie’s face and name and words through every single page. Hart tries to meditate as he walks — saying “yes” on the inhale and “thank you” with the exhale — and he can get the “yes” part right, but instead of “thank you,” he says “Rosalie": Yes, Rosalie, yes, Rosalie, yes, Rosalie. Her name stands in for thank you in the mediation, in the same way her name stands in for a thousand different words in Hart’s vocabulary: love, pain, happiness, sadness. You could strip all the words out of this comic and insert the word “Rosalie” for all of them and the point of the book would still be clear as sunlight.

You know the saying “there are no words?” It’s true. Some experiences are so universal and so raw that words can’t exist to name them. Instead, to fill those gaps in our lives we have books — beautiful, sad, funny, astonishing books, smeared thick with black ink in bands around the edges to match the achromatic rainbows that spring from the very core of our beings at the exact moment when the very core of our beings disappear forever. This book, Rosalie Lightning, is an attempt to name the unnameable. In its own way, it succeeds.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound