Thursday Comics Hangover: Nameless finally gets off to a strong start

It’s a pity that Nameless didn’t start off very well. The story opened in media res, with a nameless dabbler in the supernatural — well, to be specific, his name is Nameless — being recruited to fend off the asteroid Xibalba. The quick start perhaps wouldn’t have been as big of a problem if Morrison weren’t in his hyper-frustrating opaque mode, refusing to offer much by way of explanation for anything on the page. (Everyone knows too much exposition is a bad thing, especially in comics, but sometimes Morrison’s scripts practically throb for more explanation.)

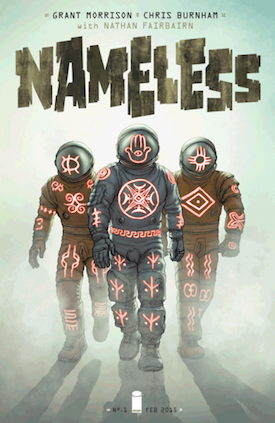

But over the next four issues, as Morrison’s intent became more and more clear, Nameless became more and more interesting. The threat evolved into something imposing, the blending of astronauts and mysticism was explored in a little more depth, and the reader was granted enough understanding to care why everyone was doing what they were doing. This is a monthly comic that will improve drastically when it is all bound between two covers in trade paperback form.

One aspect of Nameless that is beyond complaint is Chris Burnham’s art. Burnham is one of those hyper-detailed cartoonists like Geoff Darrow or Frank Quitely, the sort of artist who can draw a complex facial expression in just a few feathery lines but then spends seemingly weeks fastidiously rendering every single water spot on the chrome of the kitchen sink in the background of the panel. That blend of cartoonishness and realism works especially well for a horror series; the familiarity of a simplistic cartoon face lulls the reader into complacency, even as a monstrous betentacled demon blossoms open behind the face, with every single vein in the creature’s eye fastidiously rendered. On a visceral level, this screams something-is-wrong into the reader’s face. It’s intrinsically unsettling.

Nathan Fairbairn’s coloring, too, is exceptional. He aspires to realism in some of the scenes — a few pages in issue 5, when a group of people wander into a spooky mansion, are glowing with gentle candlelight and the warmth of burnished wood — but then a few pages later he unleashes a full-page gaudy psychedelic tableau on the reader, an explosion of turquoise and lavender and vivid, toxic red.

Nameless issue 5 is where the whole series comes together. It tells more of Nameless’s story, explaining why he was in such dire straits at the start of issue number 1. On reading this issue, with its gore and melodrama and Lovecraftian pastiche, I was left wondering why Morrison didn’t start the series off here. With a concept like this, Morrison could’ve afforded to take his time and develop the threat a little more cautiously, starting as a “normal” paranormal comic and then building to the mystic astronaut angle. Perhaps when the miniseries is done and we can see the full canvas of Morrison’s story, this decision will make sense, but for now it reeks of a squandered opportunity.