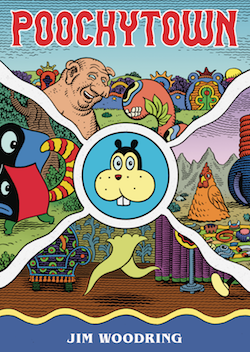

Thursday Comics Hangover: Won't you take me to Poochytown?

Jim Woodring isn't just creating a new world in his wordless Frank series of comics — he's designing an entirely new vocabulary. The Frank comics take place in the Unifactor, a densely illustrated cartoon world with its own laws and distinctive life forms. The main character is Frank, a generic cartoon character (Is he a cat? A mouse? Why is his face so...scrotal?) who comes across as a Chaplinesque innocent — albeit one with a vicious mean streak.

Every new Frank book changes the Unifactor in some way or another, adding a new element to the formula and playing out the scenario to see what happens. In the last book, Fran, Frank met up with a feminine version of himself, and the resulting interactions nearly destroyed the Unifactor.

In Woodring's latest volume, Poochytown, Frank's sort-of pets Pushpaw and Pupshaw climb into a higher plane created by a deranged musical instrument. Without his companions, Frank becomes lonely and eventually befriends his longtime enemy, the unsophisticated and hideous Manhog. The adventure involves a horse that chews off Frank's limbs, a visit to a location that resembles Woodring's studio, an out-of-body experience inspired by someone battering their head against a locked door, and one of the most heartbreaking emotional turns in the series thus far.

It's possible to read the Frank books as the comics version of silent movies — Woodring decorates all the stories with slapstick and visual gags and amusing side-quests — but they are seething just underneath that cartoony surface. Woodring is exploring primal concepts like religion and consciousness and community.

And while the surface elements of the Frank comics are just as beautiful as ever (Poochytown features some of the most breathtakingly intricate pages of Woodring's career, which is really saying something,) that deeper existential level feels as though it's growing more frenetic with every new volume. Poochytown enjoys the same moseying pace as the rest of Woodring's stories, but the inquiries he's making here on a philosophical level feel as dark and cutting as anything he's ever written.

No prior familiarity with Woodring's work is necessary to enjoy Poochytown, but after reading the book you might feel a certain anxiety roiling deep inside. That's not a mistake. More than any literary novel I've ever read, Woodring's Frank comics accurately portray the stresses and disappointments and horrifying wonder of what it is to be alive. And as being alive becomes more and more terrifying in the early part of the 21st century, Woodring's art reflects that terror right back at the reader.