Walking and writing about the land

The University of Washington Press is our sponsor this week, and they're here to show Kathleen Alcalá's new book the Deepest Roots. Our sponsor's page has more details, and the most beautiful book trailer we've ever seen.

Alcalá's exploration of food, land, and family, focusing on her home on Bainbridge Island, is an exploration of the things it takes to create a home and sustain it over generations.

It's thanks to sponsors like the University of Washington Press, and readers like you, that we're able to keep the pixels lit up here at the Seattle Review of Books. We've just released our next block of sponsorship opportunities. Check them out on the sponsorship page, and grab your date before they're gone.

Theft and art and chandeliers at Hugo House's Literary Series

On Friday night at Fred Wildlife Refuge, Hugo House events coordinator Peter Mountford thanked a big crowd of people for joining the House in what he called Hugotory — the purgatory period between Hugo House’s demolition and reconstruction, when the nonprofit writing center is hosting events in many different venues around town. Fred Wildlife is a terrific venue for the House’s Literary Series: the room feels at once large and intimate, and there’s something about a chandelier to make a reading feel extra-classy.

The last few Literary Series I’ve attended have been slightly unbalanced, in that the headline reader — the big-name writer, usually shipped in from another part of the country — has been less interesting than the local writers at the front of the show. That lack of evenness hasn’t been a deal-breaker; at every Hugo Literary Series event, at least two of the readers are guaranteed to give the kind of performance you’ll remember for a long time.

Friday had three memorable performances. Local singer ings performed soft-spoken, songs that kept with the evening’s theme of “theft” —one song’s lyrics was made up of book titles, another’s chord progression was lifted from a Fleet Foxes song. It would have been easy for ings to just perform a few covers and call it a thematic success, but she built new works from other ideas. As Mountford announced at the beginning of the night, all writers steal — the difference between plagiarism and art is that the writer does something new with it.

Poet Quenton Baker, fresh off his $15,000 award from Artist Trust, performed a suite of poems from his still-in-progress second book of poems, about the largest successful slave uprising in the United States. Before each poem, Baker named the poet he “jacked” a line or two from. The poems were about the violence committed to black bodies, and the theft on which this country was built, and Baker’s past as a rapper — which he admitted to, very bashfully, from the stage — showed through in his performance, which was relaxed and confident. His first collection will be published in the middle of next month, and it will likely establish him as a staple of the Seattle literary scene.

Headliner Téa Obreht’s short story was concerned primarily with the theft of language. Obreht said that as a Serbian refugee, she found it was fairly easy to adopt an American accent, which made her experience completely different than other refugees. Her story was about an academic encountering a young street hustler, and though nine times out of ten I’d advise writers to avoid dialogue-heavy pieces when reading, the way Obreht delivered the lines — accented, translated, always trying to find common ground and continually failing — was masterful. It’s a story that wouldn’t work as well in print, at least not without serious reworking.

The next Hugo House Literary Series event happens just before the election, on Friday, November 4th, with authors Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, Kirstin Valdez Quade, musical group The Royal Oui, and Alexander Chee. It’s worth the visit to Hugotory.

How Louis Collins made the leap from physical bookselling to digital

In the nearly five decades that Louis Collins has been selling books, he’s seen the book business completely transform itself. “I started off cataloguing books, sending out-of-print and hard-to-find books, mostly to institutions” out of his office in San Francisco he tells me. “In those days before the internet there was a magazine called the AB Bookman’s Weekly,” which served as a marketplace of rare and out-of-print books and a central meeting-place for the used bookselling community. Like many other booksellers, at the time, Collins listed all his books in catalogs, which libraries would then order from him.

“The reason I got into the book business was I have a memory,” Collins says. “Somebody would ask me ‘do you have such and such book’ and I’d either know I had it there or I’d say, ‘I saw that over in Berkeley or Oakland yesterday and I can get it for you.'” He served as a network for books, a kind of human Google with a good knowledge of books that were available around the country. People used him as a resource to track down books they’d spent their lives looking for.

Even today, “I have a really physical photographic sense of the books,” Collins says. When an order comes in on his site for a specific title, “I know exactly what it looks like and I go to the shelves and pick it up.” The books in his shop — our October Bookstore of the Month – are arranged by subject, but “not necessarily in alphabetic order.” Collins has adjusted well to the turnover to the internet — which he says hit a tipping point in the year 2000.

Bookselling has changed a lot over the last sixteen years. Some online retailers drive the cost of common used books down through automatic pricing until they’re at rock bottom — it’s not uncommon to see used booksellers drive prices down “from 59 dollars to like a penny,” in a week. How do they make money on books for a penny? “They just do volume and they get a break on the shipping because they send so much out that they get a discount from the post office,” Collins says. “I might have to pay 3 dollars for a book, and they probably pay 90 cents. Then they sell that book for a penny, charge $3.99 shipping and make $2” on the transaction. To cut costs even further, a lot of these booksellers get their stock from those book donation bins you’ll find in grocery store parking lots.

But the shift to computers was a transition he was not unprepared for — Collins believes he was the first bookseller in Seattle to have a website. “I liked the idea of computers,” Colins tells me. “In ‘93 or ‘94, I actually got a computer for the first time” to keep track of stock. As a result, Louis Collins Books is a profitable business, one which he’s training a young bookseller named Bill to take over when Collins decides he’s done with the business. But that moment doesn’t seem to be coming anytime soon. “I’m still excited to go out and make contacts and buy new collections,” Collins says.

The Sunday Post for October 16, 2016

America’s Therapists Are Worried About Trump’s Effect On Your Mental Health

The rhetoric of hate and divisiveness lead to hate and divisiveness. Trump is nothing less than the dismantling of American sanity.

Over the summer, some 3,000 therapists signed a self-described manifesto declaring Trump’s proclivity for scapegoating, intolerance and blatant sexism a “threat to the well-being of the people we care for” and urging others in the profession to speak out against him. Written and circulated online by University of Minnesota psychologist William J. Doherty, the manifesto enumerated a variety of effects therapists report seeing in their patients: that Trump’s combative and chaotic campaign has stoked feelings of anxiety, fear, shame and helplessness, especially in women, gay people, minority groups and nonwhite immigrants, who feel not just alienated but personally targeted by the candidate’s message.

The manifesto also made a subtler point: that all the attention heaped on Trump is actually making it harder for therapists to do their jobs. Trump’s campaign is legitimizing, even celebrating, a set of personal behaviors that psychotherapists work to reverse every day in their offices: “The tendency to blame ‘others’ in our lives for our personal fears and insecurities, and then battle these ‘others,’ instead of taking the healthier, more difficult path, of self-awareness and self-responsibility,” as Doherty wrote. Trump also “normalizes a kind of hyper-masculinity that is antithetical to the healthy relationships that psychotherapy helps people achieve.” Not to mention that his comments in the 2005 tape, Doherty says, are consistent with the behavior of a “sexual predator.”

The Virus With Spider DNA

A fascinating bit of biology, and how the natural world works on building blocks that influence and spread like blue dye in an ocean of water.

If you pick a random species of insect and look inside its cells, there’s a 40 percent chance that you’ll find bacteria called Wolbachia. And if you look at Wolbachia carefully, you’ll almost certainly find a virus called WO, lying in wait within its DNA. And if you look at WO carefully, as Seth and Sarah Bordenstein, from Vanderbilt University, have done, you’ll find parts of genes that look like they come from animals—including a toxin gene that makes the bite of the black widow spider so deadly.

How on earth did this nested set-up evolve? How did a spider gene end up in a virus that lives inside bacteria that live inside the cells of insects?

Is our world a simulation? Why some scientists say it's more likely than not

Lots of discussion about this lately, from all sides — liberals complaining that the Silicon Valley billionaires are playing with the fabric of our reality. But, I see this more akin to a tradition of philosophical inquiry: let's look at what is possible, and this new theory holds their attention not because it's true, per se, but because it fits. We only know what we know until we don't know it. Observing the world, and our place in it, is part of the great human tradition.

When Elon Musk isn’t outlining plans to use his massive rocket to leave a decaying Planet Earth and colonize Mars, he sometimes talks about his belief that Earth isn’t even real and we probably live in a computer simulation.

“There’s a billion to one chance we’re living in base reality,” he said at a conference in June.

The Fantastic Ursula K. Le Guin

There is no world, as far as I'm concerned, in which all the love given to Ursula K Le Guin, as of late, is misplaced.

The history of America is one of conflicting fantasies: clashes over what stories are told and who gets to tell them. If the Bundy brothers were in love with one side of the American dream—stories of wars fought and won, land taken and tamed—Le Guin has spent a career exploring another, distinctly less triumphalist side. She sees herself as a Western writer, though her work has had a wide range of settings, from the Oregon coast to an anarchist utopia and a California that exists in the future but resembles the past. Keeping an ambivalent distance from the centers of literary power, she makes room in her work for other voices. She has always defended the fantastic, by which she means not formulaic fantasy or “McMagic” but the imagination as a subversive force. “Imagination, working at full strength, can shake us out of our fatal, adoring self-absorption,” she has written, “and make us look up and see—with terror or with relief—that the world does not in fact belong to us at all.”

Dangerous Women: Tales of Queer Villainy! - Kickstarter Fund Project #41

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Dangerous Women: Tales of Queer Villainy! We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

Northwest Press is bringing you an awesome collection of 13 tales of queer female super-villainy from a roster of visionary writers.

What caught your eye?

The innocuously named Northwest Press has been cranking out LGBT focused comic books since 2010, under the inclusive banner "Comics are for everyone". If you can imagine a genre of comic, you will find it in their catalog, written with queer characters: from smutty erotica, to kids comics dealing with how to cope with bullying.

And now they're putting out their first prose collection together, and it looks great: thirteen short stories about queer villainy, written by women. Sounds great!

Why should I back it?

Northwest Press knows what they're doing — they've been around for six years, and have many books in print, and the books they print are of great quality. Kickstarter is a perfect medium for presses this size: it gives them capital to produce the books to a known audience, and gives them a chance to prove their ideas in the marketplace before major outlays for production.

So, great concept, great execution, and a Seattle press to boot. Sounds like a sure thing to me.

How's the project doing?

63% there and 23 days to go. I'm sure they'll make it, so grab your copy while you can!

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 41

- Funds pledged: $820

- Funds collected: $680

- Unsuccessful pledges: 2

- Fund balance: $220

Everybody in Seattle is freaking out about the promised weekend wind storm that has whipped Cliff Mass into one of his rare meteorological lathers. Seattle Review of Books readers should know that two scheduled readings with local authors this weekend have been postponed due to weather:

Priscilla Long’s scheduled Elliott Bay Book Company event celebrating the launch of her two new books, Fire and Stone: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? and Minding the Muse: a Handbook for Painters, Composers, Writers and Other Creators, has been moved to Thursday, November 10th at 7 pm.

Jeannine Hall Gailey’s Open Books signing for her new poetry collection Field Guide to the End of the World — read my review here — is now scheduled for Sunday October 29th from 4 to 6 pm.

Tomorrow’s storm looks like it’s going to be a big one, folks. Stay inside, stay warm, stay safe, buy some candles and junk food, and settle in under a comforter with a big stack of books, okay? We’re giving you permission.

The Help Desk: Steampunked

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Can you explain steampunk to me? I have no idea what the hell is going on there.

Danielle, Capitol Hill

Dear Danielle,

Admittedly, I've never read a steampunk book. I do know the genre incorporates the more playful totems of the 19-century industrial revolution, such as goggles and gears and steam-powered gadgets, while ignoring the less romantic aspects of the era, like child slavery and cholera outbreaks.

I like speculative fiction – American Gods is fantastic and Neuromancer is an all-time favorite – but I have a hard time getting enthused about books that play off nostalgia for bygone eras, and here's why: the 19th century sucked for most people – especially immigrants, women and children. Did you know, Danielle, that U.S. women weren't legally allowed to have bank accounts or take out lines of credit on their own, without a male co-signer, until the 1960s? Did you know that it was "recommended" that children work no more than 12 hours a day during the Industrial Revolution? Those are the kinds of enraging facts I think about when somebody mentions how cool Victorian bustles and top hats and pocket watches are. (This is also why I'm terrible at chit chat and a turd to bring to parties.)

But, again, I've never read steampunk because of my own personal bitchy biases. Like you, I don't get the appeal. But I'm willing to learn. Steampunk lovers, please send me recommendations for your favorite books. I promise to read them and report back.

Kisses,

Cienna

Is music literature?

When news broke that Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature, we published a post questioning the wisdom of giving the prize to a world-famous musician. Later that day, Seattle Review of Books co-founders Martin McClellan and Paul Constant had a conversation on Slack about whether music should be included in the same context as literature. That conversation turned into an exploration of what literature can (and possibly can’t) do. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of that conversation.

MARTIN: A baseline for poetry or literature should be pieces of textual work that stand as textual work. Performative art is something else (not lesser, but different).

PAUL: I disagree. I believe that imagining literature solely as a printed text erases the majority of the history of literature. It was spoken and sung for thousands of years before print.

MARTIN: I agree on principle that storytelling is bigger and larger, but that literature is using text to capture storytelling. Not on principle — I literally agree. Our disagreement, I think, goes to the word “literature” itself and what it entails. The OED has the first use of it in 1450(!)

PAUL: I think the distinction between a hip-hop song’s lyrics is not very different from blues lyrics, which is not very different from slave songs, which is not very different from oral storytelling. I have Jay-Z’s book of lyrics and it looks like poetry to me. If you presented it to me as a book and I had no awareness of him as an artist somehow, I would obviously interpret it as poetry. Is it good poetry? That’s a different argument entirely. But it reads as poetry.

MARTIN: I think both are valid, in that it’s fine to publish lyrics as poetry, and some would stand on their own as wonderful poetry, and if you were to give a literature award to them, it should be based on its literary, or printed, merit. But, if the transformation of the piece from good or great or whatever to sublime happens in the performance — if the text itself misses something on its own, then it’s not really literature that we’re gauging, I think. And mind you, I’m not arguing one is more or less valid, just that I see a distinction.

PAUL: Does paper have to be involved to make it literature? Static letters? Is it literature if it’s pixels? What if the text has to be moving or manipulated on a screen for its impact to be truly felt? I tend to like broad definitions, and so I define literature as the words, not the medium.

MARTIN: I think pixels are fine. I think letters could move.

PAUL: But if letters manipulated with animation are fine, what makes that any different than the letters being manipulated by voices?

MARTIN: Because the voice adds a performative element, and takes the weight of conveying emotion away from the words and puts it onto another instrument. Human voice will always be more powerful than static words, in terms of empathy-seeking.

PAUL: Wouldn’t an animated e-book do the same thing? There have been e-books that disappear after you read them, and the disappearance is relevant to the story being told. Doesn’t that add a performative element?

MARTIN: Potentially, but I’ve never seen anybody nominated an animated book for any prize. Or, no, it’s not performative, because the performance is automated. It’s a trick, like concrete poetry. The same effect could be had by handing someone a manuscript and a match and making them burn it after reading.

PAUL: The Henry Art Gallery ran a terrific exhibit a few years back of the history of e-books, and many of them were medium-specific. I’m sure that at some point in the future, when e-books shake free from Amazon’s clutches, e-book artists will create prize-worthy books. Just the same way that comics eventually became accepted as prize-worthy books.

MARTIN: Totally. And, by the way, I think comics are literature, even though they have the added aspect of illustrations.

PAUL: I disagree about the automation, by the way. I think a poet writing an abstract poem that makes a reader cast her eyes all over the page to follow a poem is doing the same thing as a singer stretching out a vowel. Or a cartoonist adding a bunch of static panels to extend a moment in a comic. Or an e-book author making words appear at a pace that’s deliberately slower than a reader’s comfortable reading speed, say. Of course, you’re a Gutenberg fanboy and I’m the ADHD-addled novelty-obsessed gadfly, so these divisions make a lot of sense.

MARTIN: They totally do. But the singer is doing more than just voicing words — they are imbuing them with emotion in a way that is very different than the words would say.

PAUL: You can imbue words with different meanings in print in lots of different ways: fonts, spacing. A thousand different writers can make the words “she stepped outside” land in a thousand different ways.

MARTIN: Of course you can, which is what makes awarding writers who convey their meaning clearly so important. Writing is hard, good writing is really hard, and great writing is nearly impossible for most writers, even. Conveying something well is hard. So, here’s an example:

Rockabye baby on the tree tops

When the wind blows the cradle will rock

When the bow breaks the cradle will fall

and down will come baby, cradle and all

It’s a good rhyme, and I can read it aloud, and analyze it. But, that doesn’t explain why it made me cry to sing it to my son the first time. And it wouldn’t have, if I was speaking it. Singing can make pedestrian words meaningful — how else can we understand U2s popularity?

PAUL: Well, but that’s the difference between good poetry and bad poetry. And sure, a good performance can make a bad poem good, but some songwriters are better lyricists than others. And besides, it’s more than the music that makes that poem meaningful for you. It’s history and nostalgia and tradition. The music, I’d argue, is the least important part of that example.

MARTIN: But one of the reason Bob Dylan’s music is powerful (if you like it) is because the forms he uses are old Americana made new by his expression. HIs music is history, nostalgia and tradition. The meaning of African-American music from slave songs, to spirituals, to blues, to rock, to funk, to hip-hop is history, nostalgia, and tradition. None of it exists in a vacuum. And, a singer can evoke that — the toolset is different than the toolset of a writer.

PAUL: That sounds like exactly what I’d expect a good writer to do: to evoke tradition, and to critique it, and to build on it in interesting ways. The only difference is in the ways you can use the toolset: music invokes the passage of time in a different way than the written word. You can’t scan ahead in a song without destroying it. You can’t listen to a song at its own pace. But you still write a song. Songs are still written. And to me that’s the most important part of literature. Sounds to me like we disagree on the output, not the input.

MARTIN: Maybe, yeah. Let me put it this way: if I were to say to a talented singer “Make me feel something without using words” she could. The writer probably couldn’t. They’d end up sounding like Jack Kerouac trying to capture the sounds of the Pacific Surf in Big Sur. Not that it CAN’T be done, but the singer has an easier job of it, because music affects our emotional centers in much different ways than words alone do.

PAUL: This is a very good argument, but a comics artist could make you feel something without words, and you said you consider comics to be literature.

MARTIN: Yes, but “words” in this case would be the baseline of meaning one could convey, so I would say the challenge to a comic artist would be to convey it without resolvable images. Easier to do than the lone writer. Abstract images can be very moving.

PAUL: I think we’ve found the atomic baseline of the argument that we might not be able to split without causing an explosion. Because if you consider an image to be a word, then should paintings be considered literature?

MARTIN: Well, no. And therein lies the rub. I consider comics literature because of the marriage of words and text. But I'd consider Lynd Ward literature and he never uses words. There are some fault points in my argument

PAUL: We’ve both got some faults in our arguments. I think the important thing is that I can see where you’re coming from.

MARTIN: My other fault: I'm trying to hang the argument on visuals because audio books are valid.

PAUL: If audio books are valid, if an audio-only book is valid as literature, then I definitely think music should count as poetry.

MARTIN: Maybe it’s the source, the creation, that is the pivot point for me. Can you use the voice as an emotive tool in the creation of the work? A writer doesn't.

PAUL: But lots of writers read their work aloud as they write. Lots of poets formulate poems by reading them in public.

MARTIN: Yes, but they write them down, as the fixative. The text is the thing, the voice is the process to get there. Whereas with music, the voice is the thing.

PAUL: Not all poets. Spoken-word poets don’t necessarily write them down. And I call back my point that if you were to encounter song lyrics in print for the first time without any previous knowledge that they were songs, you’d naturally read them as poetry.

MARTIN: We’re back to the front of our argument — I’d argue that spoken word poets who are not writing their work down are not making literature, they’re making something else. And why not make something else? I mean, I’m not complaining about the right of the Nobel committee to hand the award to who they feel is correct. My question only comes up with the classification of what is or isn’t literature.

PAUL: It’s been a lovely walk around the garden.

MARTIN: Hah, it has been a good stroll.

PAUL: As for me, I’m happy to let Lesley Hazleton have the last word:

#Dylan over #LeonardCohen? Really?

— Lesley Hazleton (@accidentaltheo) October 13, 2016

Well, it's been another banner week in the history of our great republic. The democratic process has never seemed so...well, uh. Yeah.

Maybe the appropriate way to close out your workweek, then, is to listen to KUOW's Elizabeth Austen and Marcie Sillman introduce Karen Finneyfrock's poem "The Newer Colossus," which is written from the perspective of the Statue of Liberty. Finneyfrock's version of Liberty is weary. She's seen too many anti-immigration hypocrites, from her island. "Quit your silly shit," she's basically telling us.

Hopefully, we'll listen.

Portrait Gallery: Casandra Lopez

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Tuesday October 18th: Jack Straw Writers

Poet Casandra Lopez will be reading on Tuesday with other Jack Straw Writers. She is a founding editor of As/Us: A Space for Women of the World.

Every year, the Jack Straw Writers Program selects the brightest local writers and teaches them how to better read their work. Tonight, some of the most fascinating writers in Seattle right now — Ramon Isso, Casandra Lopez, Shin Yu Pai, and E.J. Koh — will share new work and show off what they’ve learned.

University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Get painted by Christine!

Christine is taking on a limited amount of commissioned portraits, in her Seattle Review of Books style, in advance of the holidays. If you want a portrait of a friend, loved one, pet, or even yourself (immortalize your bossest selfie!) for your own wall, or as the most thoughtful gift you can possibly imagine, then please do reach out. There's more information on her website.

Book News Roundup: Is Amazon getting into the convenience store business?

- Jean Riley wrote a great roundup of the state of independent bookselling in Seattle for Seattle Magazine.

The past few decades have been challenging for independent bookstores, with each decade seeming to bring on a new threat: First, there were the huge chains that dominated the retail landscape. Then, there was the shift to online shopping, followed by the invention of electronic–reading devices. And now, the entry of Amazon into brick-and-mortar territory with its first store in Seattle. Yet despite some trepidation expressed by area booksellers leading up to Amazon’s store opening last year, the indie scene here is undergoing a quiet renaissance, as evidenced by the spring opening of Third Place Books in Seward Park, bookstore buyouts and one of the most successful Independent Bookstore Days the city has experienced.

Speaking of Amazon and brick-and-mortar stores: is Amazon really getting into the convenience store business? Apparently, the online retailer is planning on shops that would function like the"bodegas and convenience stores found in larger cities, offering customer the ability to quickly purchase both perishable and non-perishable products, like milk, meats, peanut butter, and other items." It's unclear if they'd carry books, too.

Here's a time-lapse video of the New York Public Library's Reading Room as staff prepare it for its grand re-opening after renovations:

- And speaking of the New York Public Library, did you know that the NYPL has secret apartments? Atlas Obscura takes you on a tour.

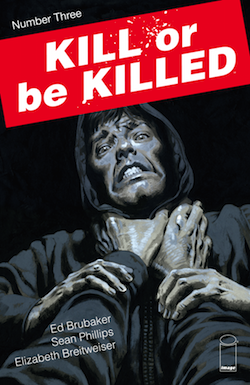

Thursday Comics Hangover: Vigilante justice

Unlike a lot of male superhero comics readers of my generation, I’ve never been a fan of the Punisher. I always preferred my superheroes to be aspirational. Murdering criminals in the street is something that only criminals do. The Punisher, to me, has always demonstrated the ugly, conservative side of superheroes, where the bad guys are an other—monstrous, irredeemable, worthy of nothing but scorn.

In the third issue of Kill or Be Killed, the protagonist, a young man named Dylan who is haunted by visions of demons, has killed his first criminal. Dylan believes that he’s made a deal with the devil — that if he doesn’t take a life, he will die — and so he chooses a criminal whose crimes have gone unpunished as his victim.

Dylan is about as unreliable a narrator as you can find in modern comics, and his narration pulls the reader in uncomfortably close. It’s like being pinned in on the bus by someone who insists on sharing their unpleasant worldview with you. Here, Dylan revels in his first kill:

It was almost like I’d peeled away a layer from the world, and I was more now… More than other people…. Last night, before I fired that gun, it felt too powerful in my hand. Like it was going to fly out of my grip or explode when I pulled the trigger. But now I don’t feel that way. I’m not so weak and full of doubt anymore.

Dylan spends much of the third issue with a young woman named Kira, trying to seduce her away from her boyfriend even as he revels in his newfound power. The reader can’t help but want to tell Kira to run; unlike series like The Punisher with muddled morals, there’s never a second of doubt in a reader’s mind that Dylan is anything but a danger to everyone around him.

Brubaker and Phillips have been making comics together for a long time now, and Kill or Be Killed is a work of supreme confidence. The comic feels dense, like a chapter of a novel, but Phillips still has plenty of opportunities to show off his hyper-detailed artwork. It’s rare to find a writer and artist who have achieved this kind of a tight symbiosis, who bring out the best in each others’ work on every single page.

And colorist Elizabeth Breitweiser’s palette for the book is another subtle nudge into Dylan’s decaying mind: every person looks a little bit grey, like they’re sick, or rotting from the inside. Only a few flourishes like the red of Kyra’s hair breaks the monotony of Dylan’s universe, and the few threats of violence in this issue pop out with bright colors. Forget the opportunities for love, or the distraction of sex — the violence, the promise of murder, is the only thing that brings Dylan, however momentarily, to life. He’s a sick, violent man who looks at the world and sees something as sick and violent as he is. Worse, he believes he’s the only one who can do something about it. This story cannot have a happy ending.

Look, I don't wanna get into a fight over Bob Dylan. But Bob Dylan is inarguably world-famous. Books and countless articles have been written about Bob Dylan's genius. Bob Dylan has won an obscene number of awards. He's made a lot of money.

And I'm just saying: Joan Didion still does not have a Nobel Prize in Literature. Or Claudia Rankine. Or Marilynne Robinson. If this was the year for an American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, seeing one of those names in all the news reports would have made my morning a much happier one.

Artist Trust gives Quenton Baker fifteen thousand dollars

Yesterday, Artist Trust announced that Seattle poet Quenton Baker received the $15,000 James W. Ray Venture Project Award, which "support[s] artistic excellence and the development of new ideas through individual and collaborative projects." Baker is going to devote the prize money to a full-length project about the only successful large-scale slave rebellion in United States history. We are so excited to see this book.

Baker, who is also a teacher, will publish his first full-length collection, This Glittering Republic, next year with Willow Books. If you're looking for some of his work right now, you should know that we published a wonderful poem by Baker titled "Love Letter" about six months ago. And if you'd like to see Baker read his work aloud, you should know that he's taking part in the Hugo House Literary Series this Friday at Fred Wildlife Refuge.

And if you'd like Artist Trust to keep giving out money to our artists, I'd encourage you to fill out their 2016 Artist Survey, which helps Artist Trust figure out what local artists need to survive in this business, and how best to allocate their resources. Your survey could help the next Quenton Baker win a grant in years to come.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from October 12th - October 18th

Wednesday October 12th: Booktoberfest

As part of Seattle Public Library’s Booktoberfest program, librarians are taking to the bars of Seattle to encourage bookish discussion with boozy Seattleites. Tonight’s happy hour is at the Hideout, which is one of the best bars in town for total strangers to sit down and strike up a conversation with each other. The Hideout, 1005 Boren Ave., http://hideoutseattle.com . Free. 21+. 5 p.m.Thursday October 13th: Noir at the Bar

Why not enjoy a night at the swankest bar in the city with some of the city’s hottest up-and-coming mystery writers? Seattle writers Scotti Andrews, Curt Colbert, Pearce Hansen, Skye Moody, Renee Patrick, Brian Thornton, Sam Wiebe and James Ziskin all present new noir, thriller, and mystery fiction with series host Will Vaharo. Hotel Sorrento, 900 Madison St., http://hotelsorrento.com. Free. 21+. 7 p.m.Friday October 14th: Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal

The Hugo House’s literary series — in which writers and musicians present new work on a theme — returns in a temporary home. Tonight’s readers include national authors (poet Eduardo C. Corral and acclaimed novelist Téa Obreht), local poet Quenton Baker, and musical guest ings presenting work on art and theft. Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030. http://www.hugohouse.org. $10-25. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Saturday October 15th: Field Guide to the End of the World Reading

See our review of Field Guide to the End of the World for more details. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St., 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com. Free. All ages. 4 p.m.

Sunday October 16th: Bryan Cranston with Sherman Alexie

Bryan Cranston — yes, the Bryan Cranston—discusses his new memoir A Life in Parts with Sherman Alexie — yes, the Sherman Alexie. This is part of Seattle Arts and Lectures’ new reading series, Sherman Alexie Loves, which features authors Alexie loves so much he apparently wants to marry them. This oughta be fun. Benaroya Hall, 200 University St., 621-2230, http://lectures.org. $45-70. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Monday October 17th: An Evening with Moss

In just a few years, the literary magazine Moss has become a central hub of all things literary and Northwest. Tonight, Moss joins forces with downtown’s newest venue, Folio, to present a reading from Eric Wagner, a conversation about the Northwest with Moss cofounder Alex Davis-Lawrence, and a musical performance. Folio: The Seattle Athenaem, 324 Marion St., 402-4612, http://folioseattle.org. $10. 7 p.m.Tuesday October 18th: Jack Straw Writers

Every year, the Jack Straw Writers Program selects the brightest local writers and teaches them how to better read their work. Tonight, some of the most fascinating writers in Seattle right now — Ramon Isso, Casandra Lopez, Shin Yu Pai, and E.J. Koh — will share new work and show off what they’ve learned. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

...and I feel fine

Published October 12, 2016, at 10:03am

You'll find a thousand ends of the world in Jeannine Hall Gailey's new poetry collection, which she'll sign this Saturday afternoon at Open Books.

The poet says what the politician cannot

Published October 11, 2016, at 1:01pm

It would be easy for Claudia Castro Luna to write fluffy poems that make us feel good about Seattle. Thankfully, she doesn't do that.