The Sunday Post for February 6, 2016

How Chris Jackson Is Building a Black Literary Movement

Vinson Cunningham profiles Chris Jackson, editor to Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jay-Z, and others, and looks into why it's important for black writers to have a black editor.

"The great tradition of black art, generally," he started again, "is the ability — unlike American art in general — to tell the truth. Because it was formed around the great American poison, the thing that poisoned American consciousness and behavior: racism. And black culture, such as it is, was formed around a necessary resistance to this fundamental lie. That’s the obligation. And this is the power that black art has."This power — the power of the unvarnished truth — is what is at stake when we talk about the problem of exclusion in the world of books. What believable version of American reality can be the product of an industry that, according to a recent survey, counts black people as just 4 percent of its employees? We can admit that race is not our only national reality without denying that it clarifies the workings of — and relations among — the others. A kind of American Rosetta Stone.

This is the unique claim on the truth that black art can make: It draws its energy from its embrace of hybridity, from a rejection of the illusion of American purity. The joy of expression and the sorrow of experience, properly commingled, might result in something new — and true.

What It Means To Be a Science Fiction Writer in the Early 21st Century

Charlie Jane Anders, with an optimistic look that the greatest years of science fiction lay ahead of us.

I believe that science fiction’s best days are ahead of it, because I have read a lot of science fiction. And if this genre has taught me anything, it’s optimism about human ingenuity—along with a belief that the unexpected is just around the corner. I’m not alone: Many people seem to feel like science fiction is healthier than ever.

Which is funny, when you consider that science fiction died in 2003, or maybe 2004.

The Problem with Female Superheroes

Don't let the headline fool you, this is no brottack on women and minorities ruining the great white superhero. Instead, this piece looks at how, although it's great to see so many superheroines getting the spotlight lately, not all is perfect between the panels. What does social research show about the influence of superheroines on girls?

But new research by Hillary Pennell and Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz at the University of Missouri suggests that, at least for women, the influence of superheroes is not always positive. Although women play a variety of roles in the superhero genre, including helpless maiden and powerful heroine, the female characters all tend to be hypersexualized, from their perfect, voluptuous figures to their sexy, revealing attire. Exposure to this, they show, can impact beliefs about gender roles, body esteem, and self-objectification.

Invisible Universe - Kickstarter Fund Project #5

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

The Invisible Universe Foundation a history of blackness in speculative fiction. We've put in $20.

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

The Invisible Universe Foundation is dedicated to researching and promoting the history of African Americans in speculative fiction (fantasy, horror and science fiction) literature, cinema and related multimedia through the activities of archiving and producing literary and media materials and presenting cultural events.

The first project is the Invisible Universe documentary which explores the relationship between the Black body and popular fantasy, horror and science fiction literature and film and the alternative perspectives produced by creators of color. This documentary features interviews with major writers, scholars, artists and filmmakers and explores comics, television, film and literature by deconstructing stereotyped images of Black people in the genres. The Invisible Universe documentary ultimately reveals how Black creators have been consciously creating their own universe.

What caught your eye?

Well, first we need to say that this is not a Kickstarter. This project was run as an IndieGoGo project that raised $6,616 (out of a $20,000 goal), and has now raised an additional $11,942 on the Fractured Atlas platform.

What caught our eye was the scope, ambition, and need of the project. While exploring how modern black writers like Octavia Butler and Samuel Delaney (just to name two) deal with the (relatively) current world of black America through their fiction, Dukan also found the Black Utopianists writers of the 19th century who did a similar thing in their time. Check out this beautiful graphic that shows this timeline.

From the clip (below), and the website (be sure to check it out), you'll get a sense of the style of the work, and what she's going for. I so want to see this film. It looks marvelous.

Why should I back it?

Did you look at that graphic? Down at the bottom, with all the writers ghosted on the poster, there is Octavia Butler, and a few people to her right, Nisi Shawl. Seattle is well represented. Wouldn't it be amazing to send some support back?

How's the project doing?

If the original $20,000 for the IndieGoGo is a measure, there's still $1,500 or so to go. But, my god, making films is expensive and complicated. I'm sure this crew could use every bit we could send there way.

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 5

- Funds pledged: $100

- Funds collected: $40

- Unsuccessful pledges: 0

- Fund balance: $940

"Welcome to our bookstore. We sell books that cannot be printed."

The headline of this post is the motto of Editions at Play, a new digital bookstore teamup between London publisher Visual Editions and Google. According to Emiko Jozuka at Motherboard, the digital books are crosses between books, movies, and video games.

“We wanted to think about what we could do online that we couldn’t do in print. How could we make books that still feel bookish—so they are books that you would read— but that you could experience as well given they are visual,” Anna Gerber, the co-creative director for Editions at Play, told me over the phone.

Maybe this sounds strange for the co-founder of a book review site to say, but I'm excited to read some of these titles, especially Entrances & Exits by Reif Larsen, the author of the wonderful (and, in its own way, multimedia) The Selected Works Of T.S. Spivet. I've always been disappointed that e-books are just a replica of physical books; if you have the capacity to use multiple techniques to tell a story, why wouldn't you?

I certainly don't think Editions at Play will ever replace physical books, but they could become a medium of their own, like comics. To do that, they need a name of their own; Vladimir Verano at Third Place Books calls them "hydras."

A Hydra will engage the reader/viewer in a multi-sensory manner; as one reads, sound effects may well up, then, at a vital moment in the story it might shift into a video clip, which might be overlaid with music or, audio narration of the text. The trend of creating 'book trailers' hints at the Hydra's possibilities. But let's make one thing clear: the Hydra is NOT a book. At least it shouldn't be. If publishers attempt to simply create what would amount to a book with Ads and some noise, then everyone loses out on new ways to tell stories.

I don't know if that particular name will stick, but it's certainly a good step forward. We need to be more intentional with how we name new technologies; otherwise, we wind up with terrible, ugly monster words like "vape."

Cecilia Woloch, whose most recent poetry collection was from Washington publisher Two Sylvias Press, has a wonderful poem in the New York Times today. "Wild Common Prayer" is a poem with long, luxurious lines about an encounter with a familiar friend in uncertain territory. It's definitely worth a lunchtime investigation.

The Help Desk: The high cost of oonce oonce oonce oonce

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Help! My boyfriend and I are both serious readers. We spend most of our nights in working through our piles of books. We even got rid of our TV.

But we didn't get rid of our stereo, and he insists on having it on while he reads. He listens to the most awful club music, all "oonce oonce oonce oonce”. It drives me crazy. I literally cannot concentrate while all that racket is on. He says if it’s too quiet, something feels wrong to him, and he can’t focus. It's like he has a second person in his brain, who he needs to distract so that he can read.

We've been alternating nights, one with music, one without, but the person who can't read that night just ends up on the goddamnned computer, cranky because they’d rather be reading their book. What can we do to address this?

Mark, on Harvard

Dear Mark,

You know who else hates "oonce oonce oonce" music? Spiders. Nothing saps the serenity of a bookish night at home more than seeing hundreds of spiders skittering about, angrily drumming thousands of tiny legs on your walls as if to spell in morse code T-U-R-N-T-H-A-T-F-O-U-L-S-H-I-T-O-F-F.

Fortunately, Valentines Day is upon us. Call me old fashioned but I can't think of a more romantic gift to get your bf than a pregnant wolf spider. If you were not aware, wolf spiders are agile hunters (with positively buxom abdomens, if you're into that sort of thing) who dislike music of any sort – even Buena Vista Social Club, a universal spider favorite! – and are known to release venom when provoked.

Alternately, you could buy your bf a quality pair of headphones. Or buy yourself a quality pair of noise-canceling headphones. What you cannot do is buy your spiders headphones. The technology simply is not there.

Kisses,

Cienna

Liam O'Brien at Melville House looks at Texas booksellers who are trying to come to terms with the state's new open carry law. Many bookstores are banning guns:

I have always believed that bookstores are forums for all ideas, but I also understand that the free exchange of those ideas can be hindered (if not entirely obstructed) when one party in the conversation holds a deadly weapon.

And one enterprising bookseller is actively encouraging guns:

Brave New Books is offering a 10 percent discount to all customers open-carrying in their store.

I know where I'd rather shop.

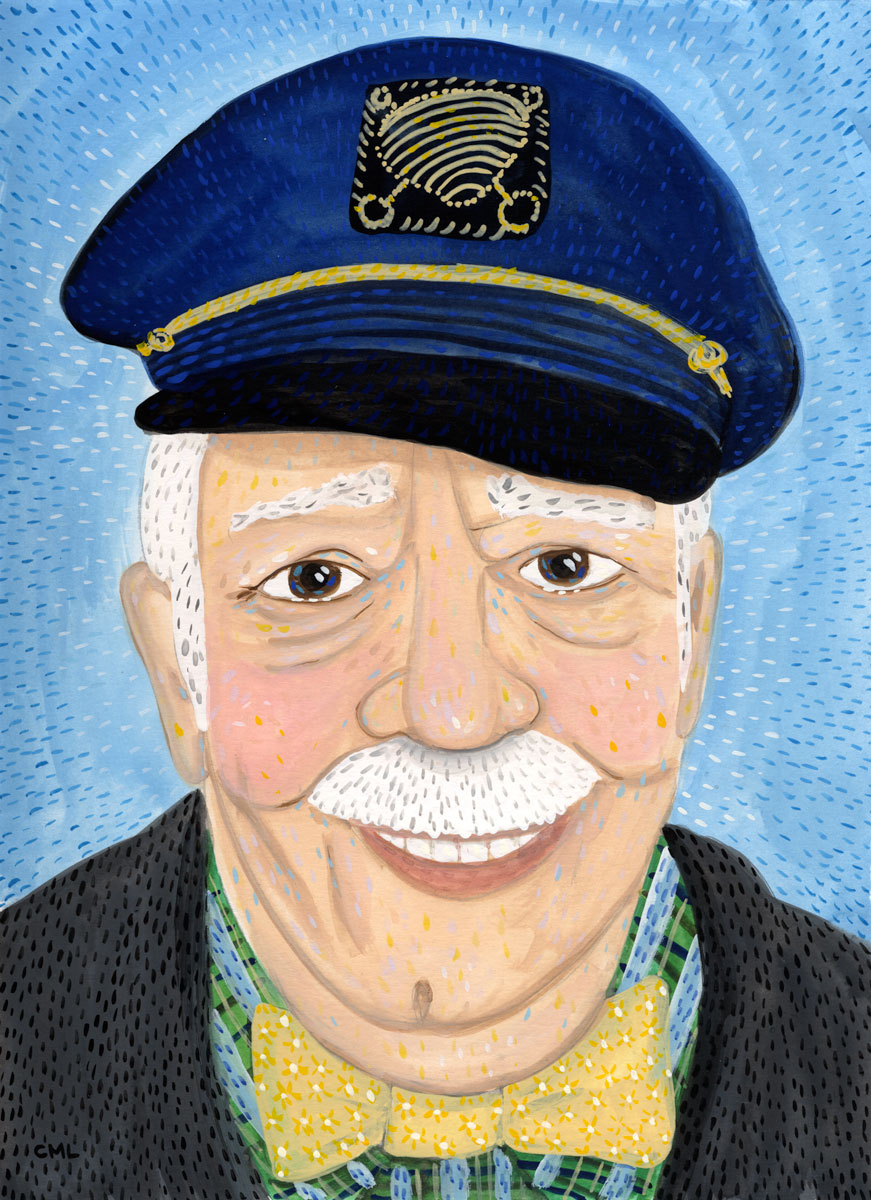

Portrait Gallery: Ivar Haglund

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Here's a painting of Seattle's own beloved son Ivar Haglund. Folk singer, restauranteur, accidental port commissioner, trouble-maker, inveterate punner (he's listed as the "flounder" of his seafood restaurant, Ivar's), and of mixed Scandehoovian lineage (his mother was Norwegian and his father was Swedish, nearly a Capulet/Montague situation). On Sunday, come to the West Seattle branch of the Seattle Public Library to hear historian Paul Dorpat discuss Haglund's life and legacy.

Unfortunately, McDonald's is distributing those books via Happy Meal.

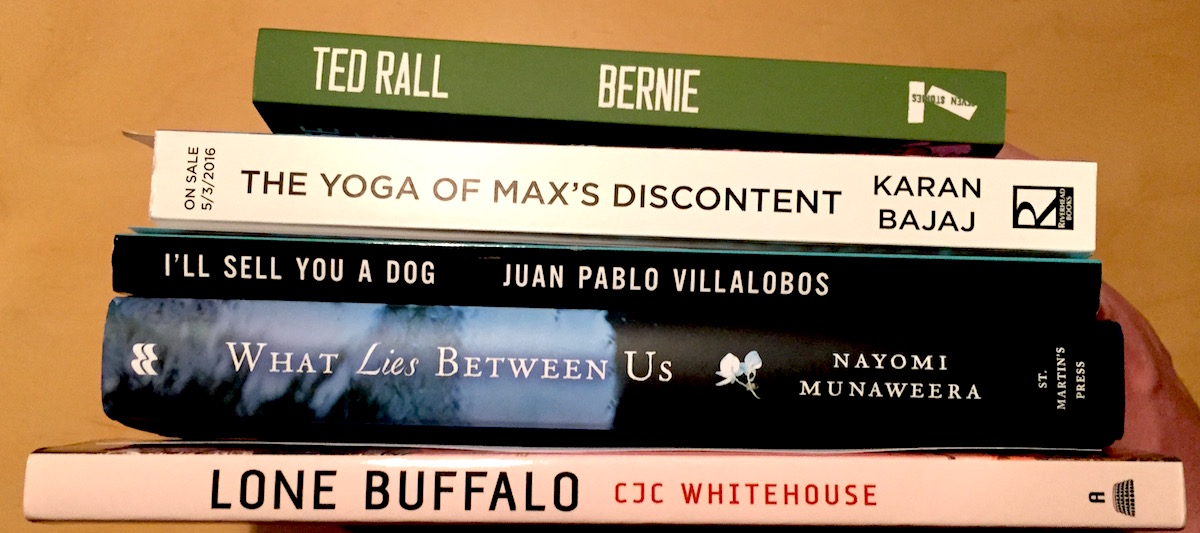

Thursday Comics Hangover: Bernie Sanders, comic book hero

Last year, cartoonist Ted Rall visited Seattle with Snowden, a comic book biography of Edward Snowden. (I reviewed Snowden and interviewed Rall onstage at Town Hall.) Only a half-year later, Rall’s back, and reading at Town Hall tonight from his brand-new Bernie Sanders biography, Bernie.

Bernie opens with a long, substantial explanation of how the Democratic party leaned to the right in response to George McGovern’s crushing defeat at the hands of Richard Nixon. Rall argues that the party has drifted steadily rightward ever since. (I would counter-argue that Barack Obama is a decidedly more liberal president than Bill Clinton, but I freely admit that this criticism might fall along partisan, rather than aesthetic, lines; in any event, Rall makes a convincing case and supports it with plenty of evidence.)

Ultimately, Bernie isn’t as good a book as Snowden was. It feels rushed, and the many pages depicting a cartoon Sanders speaking are less visually interesting than the explanatory illustrations of Snowden. Too much of the book is spent on a straight-up biography of Sanders, describing his first, failed marriage and his many runs for office. Perhaps it sounds odd to criticize a biography for being too focused on biographical details, but in a presidential year it seems as though it would be more useful to examine Sanders’s policies in more detail, to explain why they’re not too far removed from the global mainstream. Rall mentions many of the policies in passing — single-payer health care most particularly — but a thorough description of them would do wonders to normalize Sanders for a more skeptical audience.

Rall does try to provide a warts-and-all portrait of Sanders, mentioning his occasional support for NRA-approved pro-gun laws and his support for President Obama's drone assassination program. He also brings up, but doesn’t fully address, two very important criticisms of the Sanders campaign: the belief that Sanders couldn’t win the presidency and the corresponding belief that even if he were to become president, he would be unable to break Congressional gridlock to achieve his lofty goals.

But Bernie is worth your time and attention if you’re looking for an explanation of how a decent man decides to run for president. It documents a long, honorable life of civic service and the ideological battle that is right now at the heart of the Democratic Party. When sharing a bookshelf with Snowden, the two books make up a duology of honor and responsibility and citizenship. In a presidential election year, this might be exactly what the American people need to read.

Book News Roundup: Wait, how many Amazon Books are opening?

After yesterday's gossip that Amazon is considering opening hundreds of Amazon Books locations nationwide in the next few years, Shelf Awareness, the industry news site which first broke the Amazon Books story, now says Amazon's plans are more modest, likely in the range of a dozen or so stores. We at the Seattle Review of Books have heard that, too, from people in the industry. Amazon, of course, could do away with these rumors immediately, but Amazon doesn't comment on stories like these. Amazon never has any comment.

We heard some gossip last night that a long-running and much-beloved local reading series might be ending for good this year. We hope the rumors aren't true, but we're on the story and will let you know as soon as we hear something solid.

If you are a woman who makes comics, you should apply for Trailer Blaze, the Short Run festival's Ladies Comics Residency. If you're selected, you'll take up residence at the Sou’Wester vintage RV park and lodge in Seaview, WA from April 10th through the 15th. Applications are due by February 19th.

Speaking of Short Run news, here's the announcement for this year's festival dates:

SAVE THE DATE: NOVEMBER 5, 2016 The 6th Annual Short Run Comix & Arts Festival at Fisher Pavilion, Seattle Center.

— Short Run (@shortrunseattle) February 3, 2016

If I may editorialize in this news roundup for a moment, I'm glad Short Run is returning to Fisher Pavillion; it gave the festival a convention-like feel. If you'd like to learn more about the show, my Short Run 2016 wrap-up is here, and Martin McClellan's is here.

Congratulations to the University of Washington Press, which just landed a grant that will do some good in the publishing industry:

A four-year, $682,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded to the University of Washington will help four university presses and the Association of American University Presses (AAUP) create a pipeline program to diversify academic publishing by offering apprenticeships in acquisitions departments.

- Believe me, if you had the access to publisher catalogs that I have, you'd be blinded by all the whiteness of the authors. University press catalogs are often the worst offenders. This is a big get for UW Press, and I can't wait to see the new titles that come out of it. It will also likely launch a few careers in the publishing industry, too, and the publishing industry desperately needs some diversity.

"The idea was to learn a lot more about the paths of all three of the people whose lives intersected that night."

While the City Slept will almost certainly be one of the best books I'll read this year. But I worked with its author, Eli Sanders, for almost ten years at The Stranger, and so there's too much of a conflict of interest for me to review it. (We published Martin McClellan's great review of the book yesterday; you should read it.) Instead, I met with Eli on Saturday, January 23rd for an interview about the process of writing While the City Slept, the structure of the book, the benefits of taking your time to tell a story, and what Seattleites can do to fix our broken mental health care system. The following is a lightly edited transcript of that conversation.

I really like the book.

Thank you.

Which you know, it's always a little tense when somebody you know writes a book. But I very much enjoyed it. One of the fears that I have with articles that are expanded into book form is that there's not enough material to fill a book, or that it's going to feel like a padded-up version of the article. I know that's something that you were consciously aware of when you were going in to write it. It's structured like a book. It's not a blown-up version of the article, or the articles. It's full of additional information and told in a different way. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your thoughts on the transition from the article to a finished, published product.

I didn't want at all to do some sort of book-length version of the one article that people had read. I actually worry that people will hear about the book and think it is just a book-length version of that article.

So that's not what this is and it wasn't my intent. I didn't know going in exactly what I would find and what I would create. The idea was to learn a lot more about the paths of all three of the people whose lives intersected that night. Even after having written the piece about Jennifer's testimony and even having written a short feature in 2009 about Isaiah Kalebu's path in the many months before the crime, there was a lot that I didn't know.

I saw this as an opportunity to find out what I didn't know and also to do something that I had never gotten to do with crime writing before — even with this crime, which I had written a fair amount about. And that was really get into it at a length and over a period of time. I thought maybe I could do something that was more worthwhile. I felt with other stories that I've done in the past, particularly some of the very first stories I ever wrote in Seattle, which were just, like, police blotter items for the Seattle Times when I was just an intern and learning how to do this. It never felt satisfying with respect to crime writing, and I always felt like I just barely scratched the surface of what was going on and wasn't really providing much useful intensive insight.

I was curious before it came out what the classification of the book would be. On the advance reader copy, the publisher suggested to shelve it under “social sciences.” I was wondering if this is something you talked about with the publisher? I think the book's going wind up in the true crime section of most bookstores, so I was wondering how you felt about that.

I left that to them; I actually didn't even know what category they would put it in. We had a very brief conversation once. I knew that my editor was thinking about where to put it. I kind of personally liked that it was not easy to slot into one of those categories and say, "This is that thing that I've seen over and over again." I know it's not completely new, but it’s different relative to what is out there — the bulk of what's out there — when it comes to true crime.

I know you interviewed Ann Rule when you were at the Seattle Times, and she’s kind of a central figure in true crime, both nationally and locally. Do you have any thoughts on true crime as a genre?

I enjoyed meeting Ann Rule. I respect her body of work and what she did. Also, having sat with just one crime for years now as a writer, I respect the hell out of her ability to sit with multiple crimes over many years. That's not easy.

When I think about typical true crime writing — so leave Ann Rule aside, because I actually think she did try to move the bounds of the genre a bit. She certainly moved it in terms of whether a woman could write about crime — I think that there is true crime writing that exists really just to scare people. It presents a one-dimensional villain who appears out of nowhere and does something and disappears and by the end of the book is caught. The book leaves you with this kind of abstract fear that you have nothing to do with: this is going to happen to you sometime. There's obviously something exciting about experiencing that fear because people buy true crime books.

I may not know what the hell I'm talking about in terms of the motivation of true crime readers. I may be way over-simplifying what's drawing people to the genre, or to those types of books within the genre. Anyway, that is what I had in mind as what I didn't want to to do.

One of the things that sort of did put Ann Rule apart was that she did a lot more research than I think a lot of true crime writers do. You did a ton of research when you were writing the articles and you did even more research for the book. How much reading did you do? How much of the time writing the book was spent in research?

A huge amount of it was reading transcripts because it's a very long court transcript since the trial stretched over — well, the court proceeding stretched over two years because [Kalebu] was arrested in the fall of 2009 and the trial was not until the summer of 2011. There was a lot to read on that score, although I was present for a lot of the trial as well and had my personal memory of that.

Then there were a lot of court records that I had the time, once I was working on the book, to go back and dig through. There was a lot of reading court records as well. Then there was a lot of talking to people and a bit of traveling to St. Louis to meet Teresa's family and to see where she grew up. Then traveling around the Puget Sound area.

Did you encounter anything in the research that made you rethink your approach when you were writing about it in your article's perspective?

I certainly feel like the article that I wrote about Isaiah Kalebu's trajectory in August, September of 2009, I look back at that now and I wouldn't have taken that approach if I had known everything that I know now.

What specifically about the approach?

I think I didn't see a big enough picture. I do think that article identified some problems. It identified a theme that continues in this book, which is that there were cracks that he slipped through, but I don't think I saw the cracks very clearly in that article.

Also, I think I can explain it best this way: when I called Isaiah's half-sister, Deborah, to begin trying to talk to her for this story, our first conversation was her bringing up that article, which had a headline that was, "The Mind of Kalebu." She wasn't happy with me, and that was years after that article had run. She said, "How do you know the mind of Kalebu? You don't know anything."

She was right. Compared to what she knew, I didn't know anything. Compared to what I know now, I didn't know anything. I did not know the mind of Kalebu. I don't think I do now. This whole experience has made me even more aware that no one can really know, fully, another person's mind. I was aware of that before, but not quite as deeply. Her upset is also another indicator of what that article just couldn't do at the time and what I hope to do more with this book, which is provide a fuller portrait of his path and his life. Deborah, when she was willing to talk to me, has helped me paint the portrait.

In “The Bravest Woman in Seattle”, you don't name Teresa Butz's partner, which is pretty standard operating procedure. In the book you do. You've developed at this point a pretty long relationship with Jennifer Hopper. I was wondering if you could share what you're willing to share about the facets of privacy and dignity at play here? You handled them really masterfully and I think that's something that doesn't get a lot of attention because it's such a touchy issue. It’s something that a lot of journalists get wrong. Is there anything you think journalists can learn from this approach?

One of the key elements, really both for Deborah, since we were just talking about Deborah, and for Jennifer and for everyone who I talked to in this story — and for me — was time. I had so much more time than I've ever had to work on anything.

When you have the luxury of time, you can have an encounter like I had with Deborah where one day, the conversation isn't good. She's telling me something I need to hear about her anger. We can sit with that and then I can try to talk to her again in a week, or a month. Similarly with Jennifer, the ability for us to have an unhurried series of conversations about this over many years has really contributed to what you're saying is a very productive relationship and for me, unique. It doesn’t necessarily apply to other journalists. It's a hard thing to [tell other journalists to] take more time, because this business doesn't generally allow us to have it, but that has been one of the great helps to me.

With Jennifer and what you were calling that combination of privacy and dignity, she has really led the way on that. It's, again, been good to be able to just sit back and let her do that and not feel — when you're talking about advice to other people, I don't know, I don't love giving out advice, but I think errors in this realm get made when people are rushing or feeling such pressure to produce something that they do things that aren't respecting privacy.

Jennifer, you might remember, wrote a piece after the piece that I wrote about her testimony where she decided to come forward and reveal her name. She led the way on that and basically signaled when she was ready to have her name out there, very clearly. Then, in our conversations, I feel very fortunate and also quite in awe of her willingness to just be open, continually, over many years with me as I was trying to learn more about her life. We didn't have to sit there and talk about the crime because she had already talked about it and I had already written about it, so there wasn't a lot that we needed to discuss in terms of the particular details of that night. I was grateful for that, personally.

We spent a lot of time talking about Teresa and about Jennifer and about their relationship. It was a huge help to me in building the portraits of Jennifer and Teresa that I try to present in the book.

One of the more surprising aspect of the book to me was when you recount Teresa's experience with a DUI. I was wondering if you struggled with including that in the book or if it was something that you didn't have a problem with?

Do you mind if I ask why it was surprising?

No. I think maybe, there's this whole tendency not to speak ill of the dead. I think that within the context of a true crime book, there are very few authors — like Norman Mailer’s Executioner’s Song and a few others like that — who go so in-depth into people's backgrounds. I think that in a more traditional book like this there would have been, if it were the mass market paperback you’d find in a supermarket, the writer probably would have left the DUI out because it would have interfered with the narrative of…

Of a purely perfect...

Yeah. People like their victims to be innocent. The two words go together.

The reason I paused is because I was going to use the word “innocent” and I switched it to “perfect” because Teresa was innocent in terms of she didn't deserve this in the slightest. Her DUI has no connection to that.

Oh, no! You certainly don't make it seem like that.

Right, but she is not perfect. No one in this book is perfect and it's part of what I love about Teresa, and in talking to people, [it’s] what they loved about Teresa. She was a wonderfully, heart-on-her-sleeve, flaws-out-in-the-open human. It would have been wrong to sketch a portrait of her as an image of perfection. No one thought that, least of all Teresa.

But her great qualities were so great. There's a way in which you can also, I hope, see them more clearly when they're combined with the less perfect qualities that we all have. The imperfections provide a kind of relief, or a contrast, say, that allows you to see more clearly the wonderful warmth and energy and enthusiasm and perseverance and willingness to self-reflect and change as much as she could that Teresa had, that she carried with her.

No one in Teresa's life who I talked to tried to hide that she struggled at times with her drinking. No one saw that as an eternal condemnation or something like that. It was just Teresa. It was just a part of her. Her willingness to struggle with it and talk to people about it — when she met Jen, it was one of the first things that she brought up, the DUI. She brought it up to say, "That was a me that I didn't like as much and I'm working on being a better me."

I don't know. I felt like it was a part of who she was — and also in the DUI you see Teresa. She's wearing these two inch high-heeled boots that the officer remarks on. She's just been at R Place with some friends. She's driving from the center of Capitol Hill where she can have her really exciting gay life to where she was living at the time, which was Renton, which connects to the economic realities that she struggled with.

So, I included it because I thought it was a part of her and not to me an all-damning part of her. It was just illuminating in multiple ways, and a part of her stories that she didn't hide from other people and that other people didn't hide from me. I didn't go around and find this and then present it to other people. I had heard about it, so I went and looked to confirm it.

Also, people can't always place things chronologically in their memory. "It happened sometime. It was kind of before this. In this year maybe." I needed to get the record to figure out exactly when it happened. Then the record itself had details that were just so Teresa. She's sitting at a Denny's waiting for her friend to pick her up afterward.

I don't know. Maybe you can tell as I'm talking about this: I'm fond of her.

Yeah. You said, "What I love about Teresa,” which was telling, I think.

I see reasons to be fond of her in that interaction. I like her. She's not perfect. So what?

There’s a device you use throughout the book, a macro to micro effect that you use. In the opening of the book you start out with a wide-angle view of all of Seattle and then you slowly close in on the subject. In the opening of the book it's the aftermath of the crime, which almost feels to me as a reader like it's being viewed from the sky or like a tilt-shift photograph.

This happens through the book. You talk about the fault under Seattle at the opening of another chapter, and things like that. I got a sense of acclimation from it, as though you were preparing the reader for what you were about to talk about. It also opens the scope of the story and I think it exposes some randomness to the equation. I was wondering if you could talk about the decision to include this effect in the book and to return to it again and again.

As I was traveling around to see various places that were important in the chronology of this book, I was driving around the Puget Sound basin. I took in the landscape. I took in the geography and then I got more curious about some of the geological history. I guess I ended up in a conversation with it and tried to bring some of that into the work.

Yeah. It's a very Seattle-y book, and I mean that as a compliment, in that you get to talk about parts of the city that you don't see as often. Especially I think the gay and lesbian lifestyle – you know, going to R Place and other things like that. It was just before gay marriage was made legal, and all the changes that brought on. The whole book feels very much a portrait of a very particular place at very particular time.

If it's not too indulgent, just to even broaden that portrait, my hope is that it's also a portrait of a particular time in the sense of the wake of the financial crisis. The beginning of the Great Recession. The impacts of decisions that were made in that moment and also many years before that moment, and the areas where Isaiah and his family lived, grew as a family. I personally have not seen a lot of writing about those places and those aspects of the city.

Is Isaiah the only natural-born Seattleite in the book?

Yes.

He is?

Of Jennifer, Teresa, and Isaiah?

Yeah.

He's the only one who was born here in Seattle. Jennifer was born outside of Santa Fe. Actually, in Santa Fe, or spent early years right outside of Santa Fe in a small town with a really wonderful name that I can't remember right now. Teresa was born and raised in St. Louis.

Right. Yeah. Which I think also helps to make the story even more of a Seattle story, when the native Seattleites are outnumbered.

Moving on, do you think in general that it's ever possible for a non-fiction writer to be too compassionate for the subject?

I'm sure it is.

Did you worry about that? You're not in the book — you’re not a character in the book, which is admirable. I very much appreciate it. You've been intertwined within these people’s lives for so long. You're a very thoughtful person so you must have at some point started considering your connection to the story.

I'm sure it's possible to be too compassionate. I hope that I've remained clear-eyed in this book while at the same time extending deserved compassion. There are other pitfalls that a writer can fall into. A writer can be too much of a hard-ass. You know what I mean? A writer can lack compassion. A writer can just be mean. A writer could not be open to hearing things that they should hear. I try to avoid as much as I can — and I'm human — pitfalls like that. I think this is a situation that deserves a compassionate view. It's a tragedy. Everyone in it is touched by some source of pain. I tried to hear that.

There’s been a recurring theme in your work. It's sort of culminating in this book where you talk about the way our public health system has failed the mentally ill. You wrote a very good story for The Stranger years ago about a man who was randomly killed by another man with a hatchet, which — what? You made a face.

Yeah. Earlier when I was saying that I've written about a lot of crimes in Seattle — it's just how my career has ended up unfolding. — beginning with very short police blotter stuff, then more recently the crime story that you're talking about. The face was because I include that piece in the number of pieces that I feel like I got to write something but I didn't get to write this. I dipped in, then I dipped out.

It’s something that you clearly spent a lot of time thinking about. I think one of the great parts of this book is that you do the full portrait of America’s failing mental health system that I feel like you've been nosing around for a long time and haven't had the time and resources to go into. I think readers are going to want to come away wanting to do something to fix the broken system.

You talk a little bit about this in the book, but are there any signs of change or of hope with this subject? Are there any politicians making a difference? If a reader reads your book and wants to do something, where should they direct their resources?

First of all, the challenges here in Washington state are just a microcosm of the challenges that exist all over the country. We're probably talking mostly to people who live here in Washington or here in Seattle, so I'll talk about what's going on in Washington. As I try to show in the book, this state — particularly in the wake of the Great Recession, but over many many years — has slashed and slashed our social safety net. That includes our court system and our public mental health system. Both of these systems remain underfunded. Though you were asking about reasons for optimism; some of that funding has begun to come back.

People in need of help are subject to the cyclical winds of our budget crises in the state: why should that be? It shouldn't be. If people want one larger-picture thing to do, it is to not stand back and accept cuts to essential programs at a time of financial crisis or panic.

More broadly, [we need] to reform our state's revenue structure so that it doesn't gyrate as wildly and give people excuses or false senses of urgency about cutting back on mental health funding, for example.

In terms of even more specific things, a lot of these decisions go back to the state, so elect state leaders who care about public services. Let your state leaders know when you feel that public services are in danger. Even saying that, I know that it sounds boring to a lot of ears. I worry that that's the case. Fight that sense of, "this is too complex or too big to get involved in."

People need to stand up for basic services for their neighbors and for themselves. That means basic health care and robust mental health care for people who don't have money to get that care independently, without state help. There are specific policies that can be changed — aws that could be tightened or enacted — but I really think that if people can be more focused on the tremendous harm that's done by cutting back on essential services, essential social goods, and the value of investing in prevention, that would do more good over the long term than any specific thing I could point to right now.

I try to show in the book how much we have spent as taxpayers to pay for the consequences of this one crime. Of course, the impacts of this crime are not calculable on a money ledger, but voters are constantly bombarded with messages that they should make decisions based on the money ledger, on their feelings about taxes and so on. Who's going to save them money?

So, all right. Here's a way to save taxpayers money. Invest in the front end on promoting healthier lives for everyone in our community and reduce on the back end the tremendous cost and harms associated with our failure to invest in prevention.

We just did that, by the way, in King County. We just approved Dow Constantine's Best Starts for Kids measure. All of the arguments that he made in that push we could be making at the state level and we should be making more at the state level. I wish that voters around the state would respond the way voters in King County responded to Best Starts for Kids.

The choice to put the description of the crime towards the end of the story I think was kind of interesting in that it could have resulted in a lurid tone, or the sense that the crime was the climax of the book. You avoided both those pitfalls. The original article was structured like that too, so was the book always structured that way? I was wondering if you could talk maybe about the original decision, and whether it automatically translated to the book?

The way the crime is described in the original story that you're mentioning and now in the book, is through Jennifer's voice. She told this story before I ever told it. Really she is still the one telling it. I think that there's something that feels right to me about that structure. I wanted to preserve that in this book-length narrative. In terms of where to place her description of what happened that night, my instinct would be that it would seem lurid to have that happen at the beginning.

To me, that was not what I was doing. This book is — I’m not focused on telling you more details of the crime than I've already shared. I'm not focused on telling more details than a reader needs to know to have a sense of the horror of the crime. What I'm focused on is trying to show what was lost and show people, as best I can, with all my limitations, who it was, who the people are that collided in that moment and what the precipitating factors may have been and what the enduring consequences have been. Hopefully there are things to learn in that — just from Jennifer's grace and ability to get to a place of forgiveness afterward. I think personally there's been a lot to learn in that for me.

While you working on the book, you were the interim news editor at The Stranger. Right? You were working as the news editor, even though that wasn’t your title.

Right. I was an associate editor doing the news editor's job and some other jobs.

Yesterday was your last day doing the news editor job. Starting next month you're going back to feature writing in a part-time position. You haven't published very much under your byline while you were working on this book. Are you excited to get back to writing? You've talked about the short-term writing and the long-term writing— are you a little nervous about getting back into short-term writing?

Not at the moment. I'm excited to do some shorter projects, very honestly. I'll also be continuing to do Blabbermouth, the week-in-review podcast that I've been doing for The Stranger, which is also fun. It's not writing, but talking.

I'm excited about writing again, period. It's a weird thing to say, “writing again,” because I have been working on this big piece of writing — but writing other things again. If it's shorter, that's okay with me.

I do think I will want to do longer work in the future. Maybe the near future. I'm drawn to it, but I miss the quick fix of the short story that gets out there and you get something from it. I was going to say, "We are such junkies for that," but I don't know. I realized in stepping away from it how addicting, in a way, that immediacy of the feedback in blogging or in weekly writing is. I really went through a kind of withdrawal when I wasn't doing that. So yeah, I'm ready for it.

Are you under pressure from your publisher to produce another book? You can blink three times if you're not allowed to talk about it.

I hope that people would be interested in me doing another book, but the bigger thing is whether I am.

I don't know what it will be yet, but I would like to. Yeah. I would like to work on another book.

Join us in celebrating our February Bookstore of the Month, University Book Store

Quick: what’s the oldest bookstore in Seattle? Generally when you ask a Seattleite that question, they break into a blank stare for a moment and then respond, “uh, Elliott Bay?” But no. Elliott Bay Book Company turns an impressive 43 years old this year. But our February bookstore of the month, University Book Store, celebrated its 116th birthday last month. 116 years! You’d be hard-pressed to find anything in Seattle that old. University Book Store has seen the World’s Fair come and go; it was here before the Alaskan Way Viaduct, and it will be here after the Alaskan Way Viaduct. It’s survived booms and busts and earthquakes and chain bookstores and online bookselling.

Of course, a bookstore can’t just survive through inertia: University Book Store’s selection is something special. They have among the best poetry and children’s book sections in town, and their science fiction section, managed and curated by Duane Wilkins, is quite possibly Seattle’s very best. Their reading calendar is stuffed full of everything from sci-fi authors to journalists to modern masters (I saw Alison Bechdel there a few years ago; it was one of my favorite graphic novel readings of all time) to some of the most popular people in the world (they brought Elizabeth Warren to town for her memoir in the heat of the “Draft Warren” movement).

And in a city full of knowledgeable booksellers, University Book Store claims an especially friendly staff. When you visit, you’ll most likely find yourself engaged in conversation with someone — used book buyer Brad, who hosts the Breakfast at the Bookstore podcast series, say, or Caitlin in the children’s department — who’ll most likely make you excited for a book you never knew existed.

It’s difficult to imagine a Seattle of 116 years ago. It’s even harder to imagine a Seattle without a University Book Store. Almost every notable event that’s happened in Seattle history — from our first and only female mayor to the “Will the last person leaving Seattle turn out the lights” billboard to the rise and fall of cozmo.com — has happened under its watch. It’s as essential a part of our history as the Pike Place Market — and it’s older than the Market, too.

In the weeks ahead, we’ll look at some of the people that make University Book Store special. If you have any U Books memories that you’d like to share, please drop me a line on Twitter or via email.

The Wall Street Journal's Greg Bensinger quotes Sandeep Mathrani, a chief executive of a company that owns malls nationwide, as saying that Amazon could be opening as many as 400 brick-and-mortar stores in the US. It's just a rumor at this point, but it makes sense.

This, of course, is bad news for booksellers everywhere. University Book Store's manager Pam Cady recently admitted that the new Amazon Books in University Village has eaten into her store's profits, and other booksellers have expressed concern about Amazon Books opening near them. Independent booksellers and Barnes & Noble have peacefully coexisted for a decade now, but Amazon has a proven strategy of picking off brick-and-mortar bookstores. They would absolutely target pre-existing bookstores with their new outlets.

It would be an interesting time to be a writer in residence at the Hugo House; you'd be there during the transition period between the old House and the new. Why not apply? You can find details at the very bottom of this page.

Uncommitted

Published February 02, 2016, at 12:00pm

Eli Sanders won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of a horrific South Park home invasion that ended in murder. His new book expands the story, and asks a fundamental question: are we doing enough to help mentally ill offenders before a crime happens?

In Response to C.D. Wright’s “Questionnaire in January”

Suppose it is February and there are writers writing at picnic tables in the park. Suppose writing leads us to this park.

Suppose the rhythm of the afternoon sky courses through you, igniting relief and terror. Suppose you are hungry and light-headed while hoping to retrieve the faintest mark.

Suppose a writer has planted a score inside her mouth. Suppose the wind morphs that score into something fizzy and warm. Suppose everyone puts pens down at the same time. Suppose each utterance is fatal.

Suppose the wind upends food in boxes sitting on tables. Suppose the grooves inside picnic tables become embedded with crumbs. Suppose you study everyone’s furrowed brow.

Suppose the writers are all writing about descent. Perhaps to bring Rene Char’s “ship closer to its longing,” you pin your sunken hearts to the ship’s mast in unison. Suppose the collective ache is relieving.

Suppose everyone lifted their palms from the page and pages inside their notebooks shuddered. Perhaps the times you’ve shuddered before, you felt an ancestor push through violently. Perhaps you tried to smooth it out and became very tired.

Suppose you can’t fix anything at all.

Suppose a bedazzled ax appears. Suppose the ax is offered to you first, since you’ve become impatient and you’ve been given permission to get to the light any way you can.

Suppose you strike down as if you have really strong arms.

Suppose you deliciously strike a piñata, block of ice or vial of liquid. Suppose diffuse light. Suppose you stopped going over your old movies. Suppose everyone leaves their spot and takes turns with the ax.

Suppose too much strength is not a good thing.

Suppose that even when autumn is long gone glamorous winds appear like time-release golden capsules. Suppose the barren trees have long oozed your secrets. Suppose your favorite body of water is a shade of bruisy blue.

Suppose all poems are evacuation routes. Suppose the most jubilant landings are the most dangerous ones. Suppose the park has become littered with foreign liquids, depleted wind-up toys and ticket stubs. Suppose the poem has an obligation to graph each scent wafting through.

Suppose teenagers strut through park in the dark. And that dancer you remember who wore a dress made of milk jugs. Suppose your phrases get caught in the jugs.

Suppose the park’s activation points are invisible and you’ve limited yourself by staying in one place. Suppose you give up and become giddy from reciting infinitives. Suppose you look up to find everyone’s eyes glowing in the dark.

Suppose brief-lived fevers are tossed back and forth. Suppose heads bow down and collapse into the spines of notebooks. Perhaps deceit is cooled inside this heat. Suppose your fever writes you back.

Suppose someone held your head, and their hand became a rhapsody. Suppose the dark is now the color of eggplant. Suppose eyes inside eggplant. Suppose the day’s pages shuffle before you like a child’s flipbook.

This gorgeous Bloomberg tour of New York's rare book shops is to be savored. My favorite part is the painting that became the cover of A Separate Peace.