Seattle Writing Prompts: The Pike Place Market Sign

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

When you're doing a series like this — all about places in Seattle you've loved — you try to not hit the obvious spots. No Space Needle, yet (although I did write about the Monorail), and no Pike Place Market. Why? That place is one of the richest story producers our city has ever seen, from the history, to the business owners, to the senior housing and pre-school. Avoiding the Space Needle is avoiding the obvious tropes, but avoiding the Market is more difficult: it's that I just don't know where to start.

Until today. I was looking at a photo I took of the main sign at the Market — the one at the intersection of Pike Street and Pike Place, with the tall neon letters and the clock — that I had taken from the amazing patio of the apartments in the heart of the market. A friend who lives there was having a barbecue, and I was struck by this unique view of such an iconic sign.

The sign, erected around 1930, was obviously built and designed by someone who understand typography. The condensed low-waisted letters, elegant and iconic, spelling out "Public Market Center," feel both modern and old, and elegant in a gorgeous, homey way. It's very familiar. The sign is a bit like a word that you repeat over and over until it becomes alien: imagine the sign not being there, and then imagine being the person looking up into that vacuum between buildings and knowing that the right way to fill that space is big letters and a clock.

It's a stage — and not in the "all the world's a" sense — or, at least, was turned into one on a gorgeous summer's day in 2015 when Mike McCready, Duff McKeagan, Barrett Martin, and Mark Arm performed a tribute to Iggy & the Stooges in front of the sign.

And think about all the family vacation pictures it appears in. Thousands. Home 8mm movies from the 50s, Polaroids, Instamatics — all of those photos sitting in albums in homes around the world. Then we enter the digital age, and pictures are everywhere.

But we already know it's an iconic location, important to our city, the authentic heart of Seattle life (and, during the summer, an exhilarating and annoying tourist trap, especially when you just want a bag of mini doughnuts made by punks from Daily Dozen, or a loaf of bread from Three Girls, or even to drop in and buy a pint of milk from Nancy Nipples at the Pike Place Creamery. What we don't know is — what kind of stories happened right there that we don't think about? What kind of stories can we imagine looking just looking at this sign?

Today's prompts

His mom would have killed him to know he snuck away at night to look at the neon sign reflecting on the wet cobblestones, but Stanley Mouse loved the sight too much to obey her. She was busy with the new litter, anyway. So he ran up the inside of the wall and exited through the drain opening, sticking his nose into the night air, sniffing, watching the men wash the sidewalk clean of the day. Then, Stanley was being lifted, and a massive face — pierced cheeks and a nose ring — was looking right into his eyes. "Oy, check it out! I found a cute little mousie. Think he wants to join our band?"

Dad left thousands of photos, unorganized in boxes. The other kids went for his books and the paintings, but Jo asked if she couldn't have the photos. He was not a great photographer, but he had a trusty Canon AE-1, and spent their childhood capturing odd moments. It was the Seattle pictures that captured her most, the last trip before Mom died, the last time they were together — must have been '77 or so. But something in the background of the family standing in front of that sign in the Pike Place Market struck her. What was that guy doubled over in the background doing? She grabbed her loupe, and looked closer. Another man facing him, holding what appeared to be a knife. And was that blood? Did Dad accidentally capture a murder on film all those years ago?

It was supposed to happen like this: they'd get dropped off by the black car out front of the Market, and he'd get on his knee and bring the ring out when the light was red and the whole intersection at 1st was open. He had friends on the corners all set with cameras, and a drone flying overhead to capture everything. She'd been hinting for months, so he was sure of what the answer would be, and with videos and pictures to share with her family in Viet Nam, it would allow them to share the moment with her, even if they couldn't celebrate in person. That is what was supposed to happen, but of course, that was before the protests broke out that morning ...

"So, the bad guy has one weakness, and that's bronze, so he ..." The marketing director, Pat, looked up from the mockups of the comic book. "Wait, his weakness is bronze?" The artist was unphased by the sarcasm in her voice. "Yeah, bronze, so Seattle Man picks him up and slams him down in front of the market." Pat rubbed her eyes. "I don't know if I can get past this name 'Seattle Man'." The artist didn't skip a beat "I need you to suspend your disbelief, because this story is perfect. Seattle Man throws the bad guy against Rachel the Pig, and he explodes in a huge sucking vortex of energy ..." Pat nodded. Looked at the clock. "And what was the name of this bad guy, again?" The artist looked her right in the eye. "I'm thinking of calling him: the Grunge."

They had to turn off the neon at night 'cause the Japanese might decide to fly over and bomb the city, so lighting a cigarette felt downright clandestine. But tonight the moon was large behind the sign in the Market, so she didn't think too much about it. Her connection was running late, whatever the case. She pulled her collar up, and stepped closer to the Sanitary Market entrance, to shake the chill. She saw him, or rather, saw his fedora, crossing the dark street. But then, she saw the other figure approaching from the side. Then a flash in the dark, and the report of a gunshot bouncing around the cobblestones.

Is the TSA going to start rifling through your books and magazines?

The (fabulously named) Robert A. Cronkleton at the Kansas City Star wrote at the beginning of May:

Passengers at Kansas City International Airport say they recently have been asked to remove all paper products from their carry-ons while going through security screening checkpoints.

That includes all books, loose-leaf paper, Post-It notes and files. They’ve been told by screeners that the new procedures are part of a pilot program that is being rolled out nationwide.

When Cronkleton pushed, the TSA said they were not going to start screening paper products nationwide. It's kind of a confusing situation, like everything related to the TSA. Especially since Tony Bizjak at the Sacramento Bee reported earlier this week that the TSA is checking books and food at other airports, including in Boston, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles:

Some everyday items, including books and magazines, can look similar to explosives when going through the X-ray machine, federal security officials said. Screeners may “fan” through books to see if anything is hidden, TSA official Carrie Harmon said, but Harmon said screeners are not checking to see what people are reading.

Uh-huh. And I'm sure if you happen to be carrying a Koran in your luggage the TSA agents would handle your case with the same fair-handed treatment that they offer everyone else.

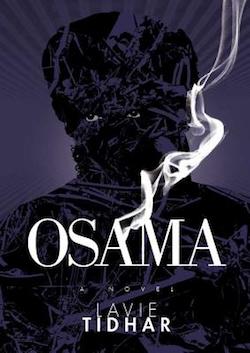

When I go on vacation, I tend to bring a lot of sci-fi with me. And there's a book that I've considered bringing with me on the last three or four vacations. It's by Lavie Tidhar and it's titled Osama. It's a Philip K. Dick-style thriller about an alternate earth in which a private detective is on the trail of a fictional character named Osama bin Laden.

Every year, I put Osama in my pile of books to bring with me. And every year, I pull it out of the pile, because it occurs to me that if the TSA comes across the book, I might have a rather large hassle on my hands. Reasonably, I know that nothing is likely to happen, but I already hate flying so much that I try to avoid any kind of friction.

And then I beat myself up for not bringing a book that I really want to read with me on a flight because someone might possibly bother me for exercising my right to read whatever the hell I want to read. And then I think about how I have the privilege to avoid conflict in most cases because I'm a clean-cut white guy, while most people don't get that choice. And then I get really depressed.

Anyway. My point is that I'm already censoring myself because I don't know how the TSA would act if they came across my reading material. I hate to think what kind of psychological effect it would have on people if the TSA were to start actively rifling through every single book they pack in their carry-on.

Is this really the image of our country that we want to project to visitors? Welcome to America — now let us probe every single page of your reading material?

The Help Desk: In a divorce, who gets custody of the bookshelves?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My husband and I are divorcing. It’s not a bad divorce, so far as these things go. Relatively amicable.

But how should we determine who gets custody of the books without having a lawyer itemize the entirety of our bookshelves? When my husband and I got married, we got rid of our duplicate copies. We almost always kept my husband’s copy and got rid of mine because he’s really good about keeping books spotless and not breaking the spines and things like that.

But just because we kept his copies, that doesn’t mean he’s entitled to keep all the books, is he? Is there a fair way to figure this out?

Delores, Maple Leaf

Dear Delores,

Congratulations on your amicable divorce! I hope to have several of those myself some day. To your question: no, your ex is not entitled to all of the books, even though they were at one point his. As every coupled person knows, you forfeit certain treasured possessions when you hitch your life to another's — books, leisurely bathroom private time, sexual mystique.

The fairest way to divide your collection is to go through, book by book, and take turns picking your favorites, like I imagine wealthier divorcees do with their pet au pairs. If your ex balks at this, follow the wisdom of King Solomon and offer to cleave each book into perfect halves. If he agrees to this plan, I decree your ex an idiot and all the books yours with the power bestowed on me by the internet. (Even more useless than half a baby is half a book; at least you can still claim half a baby on your tax returns.)

And if your ex really wants to die on this pile of books and you wish to let him for the sake of keeping things amicable, here is what I suggest: Take a few of his favorite books — books he's likely to lend out to friends or future love interests — and add some personal inscriptions that will make him deeply uncomfortable. Nothing mean, no comments on penis size or his stunted emotional capacity, just brutally honest revelations along the lines of "XXX grunts like a piglet at feeding time when he is going down on a woman," or "XXX uses the words 'irregardless' and 'travesty' wrongly and often when drunk," or "XXX got his balls waxed once and now thinks he understands the hardships of being a contemporary woman."

Kisses,

Cienna

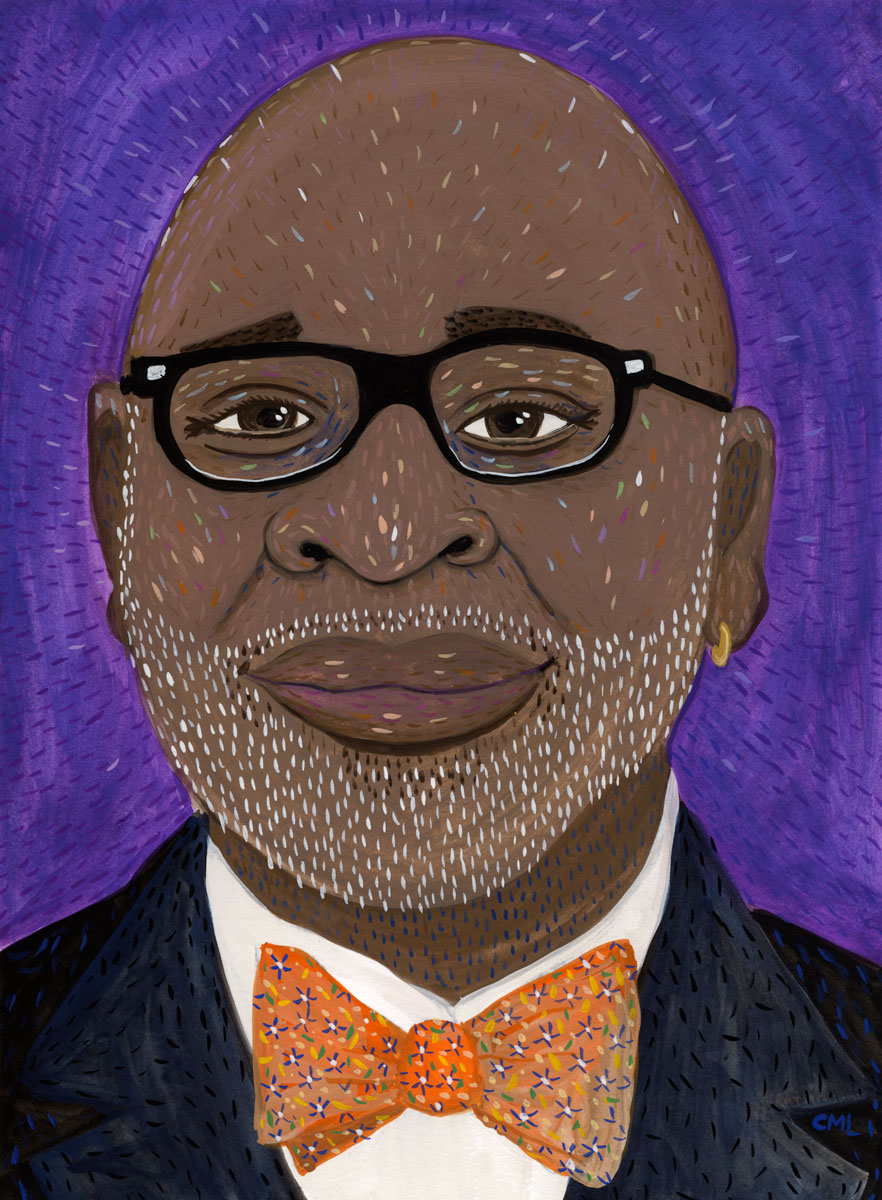

Portrait Gallery: Dr. Willie Parker

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Tuesday June 6th: Life’s Work Reading

Shout Your Abortion is presenting Dr. Willie Parker at a special Town Hall event this coming Tuesday, and attendance is required for anyone who thinks a woman’s right to choose is essential for the future of this country. At this special event to celebrate the publication of Life’s Work, Parker will be introduced by Seattle celebrity Lindy West, who helped Amelia Bonow get SYA off the ground, and Parker will be interviewed by staunch SYA ally Martha Plimpton, who appeared most recently as the mom in the sitcom The Real O’Neals. Don’t expect anyone, onstage or in attendance, to be ashamed about their passion for a woman’s right to safe and legal abortion.

Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $15. All ages. 7 p.m.

Book News Roundup: Community is something you make

- Fantagraphics Books is publishing a new comics anthology, titled Now. And Fantagraphics associate publisher Eric Reynolds explained to the Comics Reporter's Tom Spurgeon that the idea for Now came straight out of Seattle:

The idea really coalesced after last year's Short Run festival. I went to that show with a plan to really canvas the show and see what was there. I don't get to actually shop extensively at shows very often, and I ended up dropping close to a couple of hundred bucks, buying anything that looked even remotely interesting. There was a lot of good work that I felt was probably being overlooked because of either the signal to noise ratio or even just the harsh realities of distribution. If you don't live in a region that has a show like Short Run, you're likely to never be exposed to a lot the work that's there. And I came away from that show realizing that Fantagraphics can provide a platform to get the work out there.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's talk at Town Hall last night was canceled, Sara Bernard reported at the Seattle Weekly. Taylor had received death threats since publicly criticizing Donald Trump at a commencement address. Funny, isn't it, how one canceled Ann Coulter appearance can inspire the mainstream media to talk endlessly about the snowflakes of the left, but Taylor's experience barely makes a dent in the popular consciousness? Anyway, maybe you should read Taylor's new book, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation.

Megan Burbank at the Mercury reports that Portland's literary community is coming together to support Micah David-Cole Fletcher, a poet who survived last Friday's white supremacist stabbing attack. Portland poets are hosting a number of benefit readings for Fletcher, including one with an appearance by Seattle-area poet Robert Lashley.

HBO has picked up the Julia Roberts-starring adaptation of Seattle writer Maria Semple's novel Today Will Be Different.

Only eight percent of all literary magazines actually pay their contributors.

Speaking of depressing financial realities: want to make comics for a living? Better marry someone who's got a steady, good-paying job!

Thursday Comics Hangover: True colors

The future of comic books is not superheroes; it’s young adult fiction. If you look back on the last fifteen years or so of popular comics bestsellers, it’s pretty easy to track the direction of reader and creator interest, from Mark Millar to Bryan Lee O’Malley to Faith Erin Hicks. It’s not as big a shift as, say, the death of the western novel, but it’s definitely there: whereas comics used to be serialized monthly to large and eager audiences, we’re seeing more and more trilogies starring young characters (mostly girls) released in large chunks once a year or so.

The latest example of the YA push in comics is Spill Zone, a sci-fi adventure comic written by Scott Westerfeld and illustrated by Alex Puvilland. Westerfeld, a bestselling YA novelist, has clearly done a lot of thinking about how to tell a story with comics: the world-building in Spill Zone is elegant without being overly expository.

Recently, an accident tore a hole in reality in the middle of a town in upstate New York. The authorities did all the usual things they do in case of a disaster: call in the military, cordon off the affected area, and keep the looky-loos away. But while the disaster isn’t spreading, it’s not going away, either. An aura of normalcy has crept back in to the situation.

Meanwhile, a young woman named Addie has been going on excursions into what’s now called the Spill Zone. As imaginative as Westerfeld’s descriptions of the Spill Zone might have been, credit must go to Puvilland for bringing those descriptions to the page: this is not your standard “weird” comics land, where all the monsters are brown and lasers fly around in the background. The Spill Zone feels like a land where anything is possible: step in the wrong place and you become 2D. Turn the wrong corner and an abstract expressionist wolf might eat you. Get too close to the mandala constructed out of floating bowling pins and ... well, who knows what’ll happen?

But a great deal of the credit for Spill Zone’s eeriness must go to colorist Hilary Sycamore, who renders the otherworldly neighborhood in flat, ugly colors that would not seem out of place in a 1970s kitchen. These olives and burnt umbers and swirling urine-yellow tendrils make it so a reader can flip through the book and tell with just a glance which parts of the story take place in the real world and which happen in the Spill Zone. It’s not a flashy coloring choice — one blanches to think what an early-2000s colorist drunk on computer effects might have done — but it’s brilliant. The comics business is full of great colorists right now, but Sycamore has to be one of the best.

Of course, since the next volume in Addie’s story won’t be published until next year, it’s impossible to determine whether Spill Zone is the great start of a great story or the promising opening chapter of a dud. But in terms of sheer world-building bravado and technical prowess, this book is worth your attention, as full of energy and imagination and enthusiasm for the comics form as any superhero comic I’ve read in the last few years.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from May 31st - June 6th

Wednesday May 31st: One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter Reading

Scaachi Koul writes about culture for BuzzFeed. Her new, much-chatted-about collection of comic essays is about growing up in an Indian-Canadian family. Tonight, she’ll be in conversation with Seattle’s own Lindy West, who, as you may have heard, knows a thing or two about comedic essays. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Thursday June 1st: Interrupting Whiteness

The whole idea of PechaKucha is that speakers simultaneously talk and show twenty slides for twenty seconds each. It’s a fun high-wire act of a public speaking spectacle. Tonight’s event is all about investigating the question of being white as it pertains to privilege, injustice, outreach, and responsibility. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday June 2nd: Volcano Reading

Neil Matheson will discuss how geography affects the way we puny humans live our lives. We celebrate when we can see Mount Rainier on sunny days, for example, but beneath that celebration, there’s also an understanding that the mountain could, in theory, kill us all at any moment. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave., 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Saturday June 3rd: The Inheritance of Shame Reading

As a child, Peter Gajdics lived through six long years of a psychiatrist’s attempts to “convert” him from gay to straight. His memoir is about coming through so-called conversion therapy and learning how to love yourself after being exposed to so much rigorous, institutionalized hatred. (Reminder: Mike Pence still thinks conversion therapy is a good idea.) Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave., 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Sunday June 4th: Memoir Class Dismissed

Memoirist Theo Pauline Nestor regularly teaches a yearlong memoir manuscript-writing class at Hugo House. This afternoon, her 2016–17 class will discuss what they’ve learned and share some writing they composed over the course of the class. If you’ve ever considered writing a memoir, you should check this out. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Monday June 5th: Upstream Reading

Northwest author Langdon Cook has written at length about mushrooms. Now he’s turning his eye to another regional staple: salmon. (Press materials call salmon “perhaps the last great wild food.”) His new book is about the history of humanity’s relationship to salmon and the environmental impact that the salmon industry has had on the land. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Tuesday June 6th: Life’s Work Reading

See our Literary Event of the Week column for more details. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $15. All ages. 7 p.m.The storyteller-in-chief

Love him or hate him, Ronald Reagan was always a storyteller. As an actor, he wasn't especially gifted, but he devoted himself to the schmaltzy stories as best he could. Reagan really found his storytelling gift when he became a politician — when he headed the Screen Actor's Guild and then went on a speaking tour to promote political values. And then, in 1980, he took on the role of a lifetime.

SIFF documentary The Reagan Show is an expertly edited film about President Reagan's storytelling gifts. With no narrator, The Reagan Show is constructed entirely from news clips of the time, footage from Reagan's public appearances, and candid outtakes from the president's recorded messages (the best of which is probably when Reagan frets over the proper pronunciation of "Sununu" for what feels like a too-long time). Using only the evidence in the footage, directors Pacho Velez and Sierra Pettengill craft a portrait of the man that feels surprisingly intimate.

In a little over an hour, Pettengill and Velez track the Reagan presidency in more-or-less chronological order. They pay perhaps too much attention to Reagan's relationship to Gorbachev — some more attention to his domestic failings might have rounded out Reagan's foreign policy triumphalism — but the movie is never anything less than entirely compelling.

Speaking as someone who was too young to pay attention at the time, the thing that surprised me most about The Reagan Show was how in control Reagan seemed. He staged all his events — from the goofy turkey pardons to appearances with foreign leaders — down to the finest detail. JFK may have been our first TV-friendly president, but Reagan was at once the star, the director, and the producer of his own film. The media was outclassed at every opportunity.

Though I'm loath to bring him up, of course The Reagan Show has to take on a different interpretation under President Trump. For as much credit as Trump gets for his ability to manipulate the media, Reagan makes Trump look like an amateur. While Trump whines about unfair coverage and fails to present his physicality as anything but painfully awkward, Reagan understood how he would look at all times. Only toward the end of Reagan's presidency, when Alzheimer's seems to be taking its hold on him and you see some of the luster fade from his eyes and the surety dim from his step, do the comparisons with Trump make sense.

This is the story of how Reagan constructed a persona that was at once fatherly and martial. He made himself out to be both the adorable dad-in-chief and the steel-chested American warrior defending freedom from all the world's many horrors. Even if you detest the man, you'll come away from the documentary with a new respect for his skills.

And there's plenty to detest about Ronald Reagan. The Reagan Show addresses the Iran-Contra scandal head on, but unfortunately it leaves most of Reagan's other controversial policies out of the story entirely. By its nature, carved as it is out of contemporaneous sources, The Reagan Show can't offer too much by way of criticism. The media at the time loved Ronald Reagan even when it hated Ronald Reagan, and it's easy to see why: there's nothing the media loves more than a good story, and Reagan's storytelling was beyond compare.

Literary Event of the Week: Life's Work reading at Town Hall

Seattle nonprofit Shout Your Abortion really hit a nerve with its name. Founder Amelia Bonow took a lot of flack from self-described progressives when she started the organization: they supported the organization's calling, they would say, but then they would hem and haw for a second before getting to the point: isn’t it in bad taste, they’d stammer, to “shout” abortions?

They have it entirely wrong, of course. They think the name Shout Your Abortion is aimed at right-wing religious conservatives, when in fact the name has more to do with them. There’s a sanctimonious brand of liberal who likes to smugly proclaim that abortion should be “legal, safe ... and rare.” Bonow and her cohort argue that this type of thinking helps no one.

Here’s the thing: Abortion should be legal, period. It’s not your business why someone gets an abortion, and as soon as progressives allow themselves to cloak abortion in a stigma, they’re ceding ground to opponents. Hence: shouting your abortion, and offending the polite progressives who don’t realize they’re hurting the cause with their reticence.

Until now, the best book about abortion that I’ve ever read is Katha Pollit’s Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights, which made the case for abortion as a moral good and unveiled the secret anti-woman agenda behind anti-abortion organizations. Finally, we have another book worthy of a spot next to Pro: Dr. Willie Parker’s Life’s Work: A Moral Argument for Choice.

Parker is a devout Christian and an unapologetic abortionist. He tells his own story in his book, but he makes sure to tell the stories of the women he’s helped first and foremost. The book has plenty of quotable, headline-making moments — Parker equates anti-abortion laws to slavery, for example — and it also builds a complex and compelling argument for safe and legal abortion.

Parker recently told Newsweek that he believed he was “doing God’s work ... [by] protecting women’s rights, their human right to decide their futures for themselves, and to live their lives as they see fit.” There, in conjunction with his description of the abortion clinic as “a woman’s world,” is the core of his belief. He is a man who trusts women enough to believe they know what’s best for their own lives, and he knows that when women have the agency to exist without fear of government intrusion into their most personal decisions, everyone is better off.

SYA is presenting Parker at a special Town Hall event this coming Tuesday, and attendance is required for anyone who thinks a woman’s right to choose is essential for the future of this country. At this special event to celebrate the publication of Life’s Work, Parker will be introduced by Seattle celebrity Lindy West, who helped Bonow get SYA off the ground, and Parker will be interviewed by staunch SYA ally Martha Plimpton, who appeared most recently as the mom in the sitcom The Real O’Neals. Don’t expect anyone, onstage or in attendance, to be ashamed about their passion for a woman’s right to safe and legal abortion.

A white-gloved Apocalypse

Sponsor Anne Mendel delivered us a full chapter from her comically twisted dark novel Etiquette for an Apocalypse. Set in Portland in 2020, Mendel gives us a future when humanity is falling apart, people are fending for themselves, but the protagonist's mother still insists on dressing for dinner. What standards should we hold as society collapses around us?

Read the first full chapter on our sponsor's page — we think you'll really enjoy it. Visit Portland in the near future, and learn all about survival in a high-rise condo during the apocalypse.

Sponsors like Anne Mendel make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? We only have four slots left in our current set, which ends in July. Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

If you'd like to be notified when we release the next block, sign up for our low-volume sponsors' mailing list.

Good Bones

Published May 30, 2017, at 12:20pm

Great Northwest poet Joan Swift never published a book that was worthy of her talent. Until now.

Sour grapes

This past Saturday, I walked around Lake Washington. It was 52 miles — the longest I’ve ever walked, or, likely, will ever walk, in a single day — and it took from 4 in the morning until 9:30 at night.

If you ever wanted to understand the great economic disparities in King County, I’d urge you to circle Lake Washington. The Loop Trail, which at times doesn’t hew very closely to the contours of the lake, will take you near some of the poorest neighborhoods in the region and through some of the wealthiest. The closer you get to the lake, the wealthier the homeowners become, until finally they fence everyone else out and you can only see the lake as a flash of blue through chain link fences.

For the first half of the walk, I listened to an audio version of A Tale of Two Cities that I bought from Libro.fm, which made the disparities in wealth I was witnessing feel all the more acute. Eventually, I had to stop listening to the audiobook because my attention became too scattered in the heat and the mindlessness of my body on the march.

But before I turned to music, I fixated on the opening paragraphs of chapter 5, “The Wine-shop,” in which “A large cask of wine had been dropped and broken, in the street.” Of course, people run to the spot and drink the wine, scooping it up with their hands and soaking it up in fabric and catching it “with little mugs of mutilated earthenware.”

“A shrill sound of laughter and of amused voices — voices of men, women, and children — resounded in the street while this wine game lasted,” Dickens writes ...

There was little roughness in the sport, and much playfulness. There was a special companionship in it, an observable inclination on the part of every one to join some other one, which led, especially among the luckier or lighter-hearted, to frolicsome embraces, drinking of healths, shaking of hands, and even joining of hands and dancing, a dozen together.

It sounds like a street carnival, an impromptu celebration. But of course, because it’s the beginning of A Tale of Two Cities, there’s a hint of the horror to come:

The wine was red wine, and had stained the ground of the narrow street in the suburb of Saint Antoine, in Paris, where it was spilled. It had stained many hands, too, and many faces, and many naked feet, and many wooden shoes. The hands of the man who sawed the wood, left red marks on the billets; and the forehead of the woman who nursed her baby, was stained with the stain of the old rag she wound about her head again. Those who had been greedy with the staves of the cask, had acquired a tigerish smear about the mouth; and one tall joker so besmirched, his head more out of a long squalid bag of a nightcap than in it, scrawled upon a wall with his finger dipped in muddy wine-lees — blood.

And of course, because this is Dickens, as big a literary drama queen as there ever was, that blood-image is underscored multiple times and with great energy: “The time was to come, when that wine too would be spilled on the street-stones, and when the stain of it would be red upon many there.”

It's no mistake that I'm gravitating toward Dickens these days. The headlines lately always arrive with that same startling lack of subtlety. Our country is led by a buffoonish tycoon with a ridiculous name. That man just finished fomenting fear and anger in Europe either by ignorance or design, and the gap between the haves and have-nots is wider than at any point in nearly a century. Walking around Lake Washington, amidst the ugly mansions of the newly rich, it’s very hard to not notice how flimsy those fences really are.

The day after my walk, with my feet rubbed raw and my legs aching as much as they ever have, my mind wasn’t good for anything at all. It was as though walking those dozens of miles had reset my brain and I had to take 24 hours to learn how to be a human again.

But sometime that Sunday, when I was hobbling around on blistered feet and doing my best impersonation of a person, I opened Twitter and saw this tweet:

Make champagne popsicles this #MemorialDay: https://t.co/1m6ceESqnS

— Ivanka Trump HQ (@IvankaTrumpHQ) May 28, 2017

And it made me picture Ivanka Trump's popsicle cart toppled over, with dozens of ordinary Americans swarming around it, scooping up champagne popsicles with their sweaty hands and reveling in their momentary luck, their faces sticky from the melting sugar-water.

These are good times, and they’re also bad times. Perhaps most of all, they are Dickensian times.

Diaspora Sonnet 18

The workers hum to wile away

the afternoon and tenants chide

their sons to sweep from room to room

last night's dust motes — stirred dreams

entangled in wide streaks of lightthat, in the daytime, bloom,

unsparing, bright — like operatic

high notes. Pierced and round,

the clouds of sleep fill us with

sound. A loss. A tune so deep withinthe brain we cannot help but weep

as sons push brushes past door after door

locked tight like eyes and tombs.

Our quiet. Our heavy score.

Oliver de la Paz still "profoundly" misses the Northwest

Our May poet-in-residence, Oliver de la Paz, is the first Seattle Review of Books-published poet who does not currently live in the Pacific Northwest. We wanted to spotlight him because for well over a decade, he was one of the best-respected writers in town — one of those rare selfless authors who would show up as a sign of support at book launch parties even when he wasn’t scheduled to read. You always get the sense from his work and his enthusiasm that de la Paz is honored to be a part of a community that is greater than he is.

De la Paz’s work is inquisitive and bold and formally strong, which is likely a reason why he is such a wonderful teacher of poetry: the thoughtfulness and intent he brings to his work is inspirational to young writers who have yet to formulate their own discipline. We talked on the phone last week about his origins, his technique, and what he misses about the Seattle area.

When did you leave Seattle?

I left in July 2016.

And how long were you a writer in Seattle?

Well, I actually lived in Bellingham, Washington, and the surrounding area from 2005 to 2016.

Whoops, yeah, sorry. Sometimes I use “Seattle” as a catch-all for the state and then Bellinghamsters and Spokaniacs get very mad at me ...

Spokaniacs? Is that really what they're called?

I don't believe so, no. I just made it up, but I'm going to stick with it. So for eleven years you were a really devoted member of the writing community. You were one of the most-liked poets in town, based on my conversations with other poets. And you left the area for a teaching job, correct?

Yeah, now I'm teaching at the College of the Holy Cross, which is in central Massachusetts.

I was wondering if you could maybe talk a little bit about what it’s been like moving across country, because you were so well-known in the region and well-loved in the community.

I'm a Northwesterner. I was raised in eastern Oregon, and I have a lot of family members who live in the Portland area. So Seattle was relatively close by, and we would sometimes meet up in Seattle. So I actually had a lot of family members living in or around the greater Northwest metropolitan hub.

And all of my children were born in Bellingham. As far as the poetry community is concerned, there were a number of close friendships that I made and that I still hold that were fostered by being in that I-5 corridor, and driving up and down the I-5 corridor to attend readings, or to be a participant in some of the readings. I miss that greatly. I miss the folks over there a tremendous amount. I had a community that was readily on hand in the Northwest.

And I'm in the process of building a community here. Really, it's just my family and I here, and most of my friends are in New York, so it's still a bit of a trek. I've been trying to reach out to folks and learn about the literary community here.

When I was in the Northwest, each moment, each reading, was a big event, and they were always quite well attended. It may be that I just don't know my way around the community [here] yet, but it feels like, because there's a very large concentration of writers and poets, it's a big pond and I'm a little fish. And in many ways, that's okay. I like that. I kind of like some of the anonymity that's going on here.

But I also miss — you know, it circles back to the community. I have a pretty strong poetry and writing community in the Northwest who I just profoundly miss.

Since we’re on the subject, can you talk about the importance of community, as a poet? Because a lot of people on the outside, I think, view writing as this sort of solitary at best — or misanthropic at worst — sort of lifestyle. And do you teach community to your writing students?

I believe art and the making of art is actually a collaborative exercise. I think that, you know, so much of the belief in writing is that it is indeed a solitary exercise. And part of that is true. Part of the endeavor of writing is being alone and delving deep within one’s own self.

But then there's that other part that, once the writing is done, in order to elevate it to the level of art, you have to celebrate it in the public sphere. And that is something that I'm trying to, you know, build back up for my own self here. But it was definitely something that was fully abundant in the Northwest, with that community of writers.

Communities are really, really essential, because there are ways that art can get lost if it's not performed or it's not shared in that public sphere, in that communal air.

I do want to add, Seattle is really, really fortunate to have a center like the Hugo House and the Jack Straw programs and Artist Trust and, of course, the Seattle Review of Books. There's some really great communities and networks for writers to get a handle on in the Northwest that I'm glad that I was able to take advantage of when I was there.

That first poem [published on the Seattle Review of Books in the first week of May], “Diaspora Sonnet,” that was a part of piece that was written in collaboration with Kundiman Fellows. Kundiman is an Asian-American literary arts organization that I have been a part of for quite some time now. And we were actually writing a number of these postcards and sending them out to each other; “Diaspora Sonnet” was one of the poems originally on a postcard.

The idea of community has been foundational to my pedagogy, my teaching. Part of the writing of art is also the celebration and elevation of art in the communal state, so that you are not just an artist, you are an artist-citizen. I find that family essential to the making of art.

And we're kind of moving backwards here, but I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your journey into poetry. Did you always know you were a poet, or is that something that came to you later in life?

When I started out in writing and letters, it was really by accident. My parents were immigrants — they immigrated from the Philippines in 1972. One of the first things that they did as new immigrants was they subscribed to Reader's Digest. And one of the benefits or perks of being a subscriber to Reader's Digest was you would get access to their book catalog.

And my father, who is pretty literate, and literary, and a reader, selected a whole bunch of books. And one of the books that he selected was The Selected Poems of Robert Penn Warren. Which is really bizarre.

I think that he picked Robert Penn Warren’s selected poems because All the King’s Men was sort of making a splash in the 70s and, you know, my father wanted to buy into that. That was my first poetry book, and it was bizarre. It was a very curious thing.

Flashing forward a little bit, I decided not to be a poet but to be a doctor. I was a pre-med student, and I was taking all these science classes at Loyola Marymount University. And you had to take classes in the humanities.

One of my classes was a poetry class, and I dug back into my memories of going through the Robert Penn Warren book and trying to experiment with poems on a typewriter. I wrote some poems for that class, and the teacher liked them and really encouraged me to keep writing. And eventually I got a minor in English, which ended up becoming a second major. And then I just decided, hey, this is what I wanted to do. This is what I wanted to pursue.

But honestly, I didn't really take it seriously until I was admitted into grad school for it — for the writing, for poetry. I just thought, “this is something to tide me over while I try to get into medical school, or while I pursue my degree in microbiology.”

Quite honestly, I was a scientist. I was deeply entrenched in the scientific field.

There’s obviously precedent with William Carlos Williams, as a doctor who's also a poet. Was that something you considered?

At the time, I had no idea. The weird thing is I was an EMT while I was writing, in Los Angeles County. And while I was an EMT, the LA riots happened. And so storefronts were getting burned out, and I had a horrible time, and it kind of turned me off to the whole endeavor.

I felt that I didn't have the temperament for the medical profession. And I think it was an extreme case, but it was just something that turned me off from it.

I just found I didn't have the temperament. I couldn't stomach it.

Wow. Sorry to do this, but circling back a minute, I don't think I realized that Robert Penn Warren wrote poetry. Can you tell me a little bit about what it was like? Did you like it? Do you like it now?

No. No, not at all.

It was really odd and folksy, and he did a lot of experimentation with lineation and line break. There's a lot of white space.

I honestly don't remember much of it. It left that strong of an impression on me. All I remember is the physical space of the poems on the page, and that was what I was trying to duplicate.

I was really interested in the dynamic quality of what a line break looks like, and what a typewriter can do, and what pushing back that carriage return does to my wellbeing. So it was more of a physical response than an actual aesthetic understanding or an intellectual understanding, if that makes sense.

Do you still write on a typewriter?

No, I don't. I’m one of those terrible people. I write everything on a word processor, and I don't even save old drafts. I used to. I used to be pretty compulsive about that, but I just stopped because I was creating so much clutter.

I was the last generation in my high school to learn how to type on a typewriter, and I kept one around for a while. And my writing is very different on a typewriter — more aggressive and clipped, I think in part because of the mechanical nature of the carriage return.

Yeah, it was something that hummed in the body. You type, then you reach that end of the line, and then you would take your right arm and just shove that thing over to the left, pushing it all the way back, and it would make that great sound. That was writing to me when I was growing up: physical, kinesthetic.

I don't have anything to duplicate the physical interaction with the typewriter now, other than I actually listen to a lot of music and I kind of zone out when I'm writing. That's kind of the closest thing that I can think of at this moment.

So do you listen to music with lyrics when you're writing?

No, no I can't. That would drive me crazy. I listen to the band Explosions in the Sky, and some others. I like a lot of lot of fuzzed-out stuff, and even classical jazz that has no lyrics and no speaking.

If there was speaking or the human voice [in the music], I think it would mess with what I was doing on the page — or I should say the screen, since I'm not using a typewriter.

I wanted to thank you for sharing your poems with our readers. I think that it's an interesting mix of poems. You've got the Prince elegy and the story problems — there's a lot of humor in there. Do you think that this sampling, these five weeks, are representative of your work? Or what would you want someone who doesn’t know your work to know about these pieces?

That's an interesting question. I honestly don't ever think of myself as a humorous writer, or that what I'm doing is humorous. Except for the Prince poem. I thought that I was being intentionally cheeky with that poem, even though I wanted to elegize him. That was a poem that I had written immediately after finding out that he had died.

The story problems were never intentionally humorous, although I do think that they can be smartly funny or taken ironically in some regard.

And as far as a representation of my work, I'm constantly shifting what I'm doing. Out of boredom, or out of an understanding that sometimes a project needs a different set of principles or guidelines to push forward.

The story problems are actually a way for me to solve a problem I found in a current manuscript that needed some type of interruption — to keep it from being so much of a one-note thing. So I tried to shift direction, there. And the Diaspora poems are closer to the type of lyrics that I like to write when I'm writing shorter pieces.

But honestly, I still can't pin down what it is that I do, because often what I'm doing is in response to stuff that I'm reading. I read a lot — constantly.

We talked about how writing takes place in the community. I believe in a community of writers. Every time I write, I'm constantly responding to work that I'm reading, and sometimes that changes the shape of what I'm writing.

Okay. That's very interesting to me, obviously, since I co-founded a book review site. And also because a lot of poets seem to find their groove and then stick to it, but I don't know if I can pin a distinctive style on you. So I feel like that's some interesting insight in that your writing is in a relationship with your reading life. Do you read broadly, or do you read along certain avenues, or do you just happen across books?

I will look at who's winning the NBCC and the Pulitzer and the National Book Awards. I'll look into all of those books and I'll read all of them.

But I'll also dig into Small Press Distribution, stuff that's maybe a little more edgy and more experimental. And a lot of times when I do that, when I dig into some of the more obscure or experimental works, I'm hunting to find a way to solve a problem that I'm encountering in my own work that is not solvable by conventional means. Just to see how other writers are approaching analogous issues of writing.

Do you read a lot of poetry or prose, or both?

I read a lot of poetry. I basically read at least a collection a week, if not more. I just read Lily Hoang’s A Bestiary, which was a collection of lyric essays. She makes use of a lot of white space, which is attractive to me. That was something that was exciting to me as a poet, seeing how a nonfiction writer tackles long forms.

I've read a lot of Maggie Nelson; Bluets in particular was something that I loved. I look for nonfiction folks who write lyric essays and that's the other thing that I've been reading.

But I do read quite a few novels, and I listen to a lot of books on tape. I just read The Underground Railroad by Whitehead. If I could show you my library — it's so crammed with stuff right now, and I'm reluctant to give any of it away.

How much of it came across the country with you?

Almost all of it, which is insane. I tried to have a thing at my house where I was giving away books, and nobody took anything of great note. They took maybe like 200 books, but that didn't put that much of a dent into my collection.

I have a lot of books. And so I basically hauled them all across country, and that was the bulk of my freight cost.

What are you working on now? Do you have a break from school from teaching?

I do, yeah. It's now summer.

Congratulations!

Thank you. I'm so happy to have summer.

The story problems are part of a book project. It's a sequence of prose poems based on my son, who's on the autistic spectrum.

Part of what I'm attempting in that collection — the problem is, I'm trying to find a way to write about him, while allowing him the dignity of his selfhood. And that was one of the more difficult things to consider when I was writing these. For a long time, I was really reluctant to even start writing about it, but he gave me permission.

There's an allegory that's running through the book, but then I needed some type of interruption from the allegory to make it biographical. That's where some of these mathematical problems are coming in, and that's where the story problems come in.

Can I ask how old is your son is?

He's nine years old. And he is quite a dude. He's interested in science. He's a hell of a mathematician.

You know, he's a total iPad junkie and video game nerd, which is kind of my type of people. And he's genuinely interested in the world, which couldn't make me happier.

It's interesting to me that you say you're a video game person, because I would think that would get in the way of the reading. I had to make a conscious decision to not get into video games because I wanted more time for reading. So, I'm impressed that you can do both.

I can barely sustain it, Paul. I mean, I can really barely sustain it. But in the summer I'm good — really well behaved.

Is there anything that you wanted to express to the readers of this site?

No, except that I just miss the Northwest terribly, and I miss my colleagues and my friends. And I will be back in late July/early August for the Pacific Lutheran University low residency.

Okay. And are you doing any readings in that time?

Yeah, I think I'm going to be reading for PLU's faculty reading — I believe it's the first Tuesday of the residency.

Okay, please let me know when you confirm it, because I would like to let people know about it. I know that you are terribly missed here as well.

Thank you, Paul.

The Sunday Post for May 28, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Beleaguered Tenants of ‘Kushnerville’

Withholding maintenance as a power play, hardcore debt collection, and public shaming for late rent — sounds like a classic slumlord. Or, maybe, Jared Kushner. Here’s Alex MacGillis on what it’s like to live in a property owned by the president’s son-in-law.

The worst troubles may have been those described in a 2013 court case involving Jasmine Cox’s unit at Cove Village. They began with the bedroom ceiling, which started leaking one day. Then maggots started coming out of the living room carpet. Then raw sewage started flowing out of the kitchen sink. “It sounded like someone turned a pool upside down,” Cox told me. “I heard the water hitting the floor and I panicked. I got out of bed and the sink is black and gray, it’s pooling out of the sink and the house smells terrible.”

Cox stopped cooking for herself and her son, not wanting food near the sink. A judge allowed her reduced rent for one month. When she moved out soon afterward, Westminster Management sent her a $600 invoice for a new carpet and other repairs. Cox, who is now working as a battery-test engineer and about to buy her first home, was unaware who was behind the company that had put her through such an ordeal. When I told her of Kushner’s involvement, there was a silence as she took it in.

“Get that [expletive] out of here,” she said.

What If We Cultivated Our Ugliness? or: The Monstrous Beauty of Medusa

On the same day that The Washington Post praised Melanie and Ivanka Trump for being pretty, stylish, and silent, Jess Zimmerman posted a call for women to embrace ugliness. It’s hard to pull off without sounding like sour grapes, but she threads the needle brilliantly — not anti-beauty, just pointing out that there’s more than one game in town. Naming Medusa the patron saint of not-lovely women doesn’t hurt.

There is no male-controlled culture that by default sees women, that allows women to be seen. In my country the government doesn’t (yet) require us to cover our faces, but don’t confuse that for visibility: We’re obscured not by cloth but by disregard, by the way men are taught to devalue us and we are taught to devalue ourselves. It’s beauty — and specifically femininity, and even more specifically, sexual attractiveness to men — that burns through the veil.

People look through your face, or past it, when beauty doesn’t focus them, when there’s nothing there they want. They’re not afraid to meet your eyes—they just don’t see the point.

Better for them to be afraid. Better for them to think they’ll turn to stone.

See also Mary Beard, more scholarly but no less righteously pissed off, on monsters, myths, and women in power.

Never Write a Novel With an En-dash in the Title

If you missed the reading by Seattle’s Nicole Dieker last Tuesday (or even if you didn’t), you can catch up with her at The Awl, where she’s chronicled the journey toward self-publishing her first novel with great wit and self-effacing charm.

Whether your novel will be a success is still to be determined — though you can guess already that it might not, five-star reviews and Ferrante comparisons aside. It is successful because you did it. It is financially successful because you have not yet spent more, to publish and promote the novel, than you earned from the Patreon project. You can say all of these things but you know there is another marker of success out there — well, multiple markers, because you know that the trad publishing world counts a “successful” literary fiction novel as one that sells 3,000–5,000 copies, and you also know that there’s the type of success that derives from momentum; from being good and having everyone talk about you at the same time.

You do not think you will have that kind of momentum, for the same reasons you weren’t ever popular in high school.

The Exquisitely English (and Amazingly Lucrative) World of London Clerks

There’s a numbing volume of subculture reportage on the internet, rapidly catching up with the ubiquitous personal essay. Simon Akam’s piece on the British legal system — specifically, the political, financial, and class-haunted relationship between the barrister and the clerk — stands out. Informative, bemusing, and vital background reading for fans of Sarah Caudwell and many others.

At a chambers that had expanded and was bringing in more money, three silks decided their chief clerk’s compensation, at 10 percent, had gotten out of hand. They summoned him for a meeting and told him so. In a tactical response that highlights all the class baggage of the clerk-barrister relationship, as well as the acute British phobia of discussing money, the clerk surprised the barristers by agreeing with them. “I’m not going to take a penny more from you,” he concluded. The barristers, gobsmacked and paralyzed by manners, never raised the pay issue again, and the clerk remained on at 10 percent until retirement.

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Seattle Tower

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

There it stands, on the corner of 3rd and University. Twenty-seven stories tall, completed in 1928, this deco-style brick tower was a shining example of Seattle's upward momentum in the early part of the 20th century. It's a lovely building, and it's on the US National Register of Historic Places.

The problem is, talking to people from New York or Chicago, they have dozens — hundreds? — of buildings that raise to the mark of a modest deco tower such as this one. They won't think twice, like when the great museums who hold iconic works by painters don't think twice about smaller museums with lesser pieces, and they'll tell you how that building is nothing compared to what their city holds.

But a city holds what a city holds, and this beautiful tower is unique, and all ours. Did you know they graded the brick in 33 shades to make a facade that started dark and lightened as the tower grew? Did you know that 300 lights were used to illuminate the facade, to emulate the northern lights, and that's the name the locals gave the building?

I've been lucky enough to visit businesses in the building a number of times. A lovely marble lobby leads to classy elevators. The floors feel ... well, old. They don't seem modern, but they shouldn't, right? In one conference room, a window opens onto 3rd Avenue, and one could just hop on out onto the ledge where the spotlights used to sit.

I wonder if the owners have considered lighting it up again? I think it would be marvelous if this building — one of my very favorites in the city — called a bit more attention to itself.

But for now, let's see what stories we can find inside of it.

Today's prompts

It was a black cat, on the ledge, and there was no way that she was going to let it get stuck. By the cat was shy and wouldn't come in the twenty-third story window. Well, no doing, she'd have to go after it. She climbed out onto the ledge, and the cat ran around the corner. Then she looked down, and realized, it would be an awfully long way to fall. She grabbed hold of some brick for dear life, and was paralyzed on the spot.

Leaving your job is hard enough — you fill your box with all your stuff, and make that embarrassing walk in front of all of your now-ex co-workers to the elevators. It's even worse knowing the Depression will make them all have the same fate soon enough. But it's triple worse when your boss is introducing a new hire as you're leaving, and you know two things: that person is going to lose their job any day, and that when you were making the walk of shame, you caught each others eyes, and ... wow. Fireworks.

He called himself Spider-Man. He was going to make the news that day by scaling the Seattle Tower. It was going to be a brilliant stunt. All the talk shows would want to talk to him. Sure, it wasn't the tallest building in Seattle in 1977, but it was one of the most iconic, and frankly, the easiest due to the facade construction. He set out, around 6 a.m., and approached the building from the 3rd Avenue side, looking up, feeling ready and excited. But something caught his attention from the nearby newsstand. A radio broadcast — a man, calling himself the Human Fly, was climbing the World Trade Center, and he had been at it for hours. Today, of all the days.

There were 300 lights on the outside of the building, and it was his job to change them when they burned out. For fifteen years those lights shone up, making a gradient from the ground to the top, emulating the northern lights. In fact, that's what the locals called it — the Northern Lights building. But now, in 1942, the West Coast was going on blackouts to avoid giving Japanese bombers targets. So now it was his job to go dismantle every single fixture so that they couldn't be turned on, even if by a traitor.

First day in the brickyard his boss said, "Look, kid, I don't care how you do it or what you do, but the crazy architect wants us to sort these by color. Just break them into three or four groups by the way they look, got it?" He got it. He got that his new boss didn't know how to use his eyes. The problem wasn't sorting a mountain of bricks into three groups; the problem was going to be sorting them into less than three hundred.

Book News Roundup: Neil Gaiman at the Cheesecake Factory

Seattle's Office of Arts & Culture is accepting applications for its CityArtist Projects grant, which provides funds for artists seeking to complete a project. The grant changes disciplines every year, and literary artists are up for consideration this year. You have 55 days left to apply, so get to it.

Ted Closson's cartoon at The Nib titled "A GoFundMe Campaign Is Not Health Insurance" is required reading. It seems that every day I see another writer or musician or artist in medical distress whose lives depend on the outcome of a GoFundMe campaign. This, of course, is total bullshit.

Speaking of crowdfunding, here's something: "Neil Gaiman Will Do a Live Reading of the Cheesecake Factory Menu If We Raise $500,000 for Refugees."

At The Atlantic, Asher Elbein writes about the turbulence that Marvel Comics is experiencing at the moment. It turns out that Marvel isn't flailing due to an increased drive toward diversity (as some dipshit white men on the internet claim). In fact, Elbein argues, the company has fallen deep into a negative feedback loop of insularity and ego.

At The Beat, Heidi MacDonald backs up Elbein's column with her own observation:

...I came upon yet another problem for Marvel: working with libraries – another source of easy money for most publishers – isn’t much of a priority for them...As one prominent librarian put it to me, “People [in the library space] ask me is there a way to contact Marvel and I say, ‘nope it’s just impossible.’ Often, they’re people who want to buy 200 copies of something. I say ‘Good luck!'”

I just want to confirm MacDonald's experience and add that Marvel never supplies the media with review copies, a weird policy held by virtually no other publisher in the business. Additionally, I've talked to multiple writers over the years who argue that, for a company that likes to brag about the high value of its intellectual property, Marvel pays its contributors very little. Maybe if they actually invested in their people, Marvel wouldn't be suffering from low sales?

Yesterday, Amazon opened its first Amazon Books brick-and-mortar store in New York City. Thu-Huong Ha from Quartz didn't enjoy the experience:

The store doesn’t let you escape the noise of shopping online: One section is for books with more than 10,000 reviews; another display is for “page-turners,” based on ebooks that customers have read in three or fewer days; with a few exceptions, books need a 4-star review to be in the store; to enter, you have to walk around a table showing books 4.8 star-rated or higher.

Of course, the Seattle Review of Books visited the very first Amazon Books store in University Village when it opened two years ago. We were horrified.

We've visited Amazon Books a few more times in the intervening years, too.

We're still horrified.

The Help Desk is taking Memorial Day weekend off

Our advice columnist, Cienna Madrid, is taking the weekend off to celebrate Memorial Day and do a little traveling. Hopefully, you're doing the same.

If you have any questions of literary etiquette — from the proper treatment of rude library patrons to what to do about loved ones whose lips move when they read — please drop Cienna a line at advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com. And of course you can always read the archives of the column right here on the site.

Denis Johnson, 1949 - 2017

Writer Chris Offutt reports on Twitter:

Yes, it's true. Denis Johnson died yesterday morning. He was at home, peaceful.

— Chris Offutt (@Chris_Offutt) May 26, 2017

Based on the high number of mourning authors on my Twitter feed right now, it's fair to characterize Johnson as a writer's writer — one of the greats, a talent so advanced that it mystifies peers.

Jesus' Son has to be one of the best short story collections of the 20th century, and The Name of the World is a magnificent short novel about grief and loss and people-shaped holes in lives. As news of Johnson's passing spreads, I expect many people to be pulling The Name of the World off their bookshelves tonight.