Thursday Comics Hangover: The possibility of an Island

(Every comics fan knows that Wednesday is new comics day, the glorious time of the week when brand-new comics arrive at shops around the country. Thursday Comics Hangover is a weekly column reviewing some of the new books that I pick up at Phoenix Comics, my friendly neighborhood comic book store.)

Serialized anthology comics are tough. They’re a pain to coordinate, for starters, and it’s hard to find an audience for a series of short, ongoing stories by a wide array of artists. I want to support anthology comics — Monkeysuit, a lively anthology back at the turn of the century was a particular favorite — but I have to admit that I often can’t be bothered when a new anthology starts up. Too much of an investment, too little return. For the most part, they disappear before they even really get started.

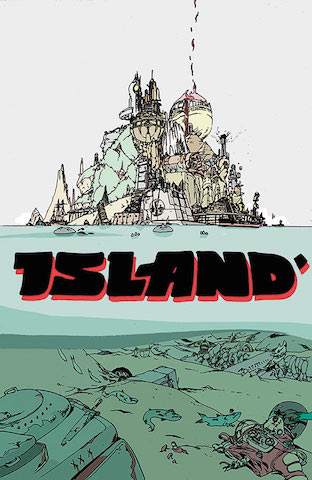

So I wasn’t planning to pick up the first issue of Island, the new anthology edited by Brandon Graham, but, hell, you try to ignore it. It’s a massive book for a monthly comic — over a hundred pages, squarebound, drawing in your eye the way light gets sucked into a black hole. The cover kneecapped me, with its intricate drawing of an island made up of many parts (a forest, a sci-fi spaceport tower, a temple, a sailing vessel straight out of Moby Dick moored to one side) and its moody blue-gray color palette. Nothing else on the stands looks like this. I had to have a copy because it was a beautiful object and sometimes it feels good to own a beautiful object. And even at $7.99, a dense, full-color comics anthology feels positively European, the kind of artistic endeavor you should want to support.

Like all anthologies, some of the stories in Island hit me harder than others. My favorite story was the one that opens the collection, “I.D.” by Emma Rios. A support group meets in a coffee shop. Rios tells her story in tightly cropped panels, claustrophic and tinted only in shades of red. Gradually, we see that the story is set in the future — people start discussing an interplanetary mining colony operation — and we learn that the support group is for people seeking body transplants. “My metabolism doesn’t allow me to be the man I want to be,” one character says, adding “I can’t stand being this weak anymore.” Just as the story starts picking up, something happens and then it’s To Be Continued time. It’s an excellent first chapter to a longer story, ending not on a shameless cliffhanger but at a point of change for the characters.

Comics author Kelly Sue DeConnick contributes a four-page prose essay about a friend who helped her become an author. “I was newly sober, which is a lot like walking around with no skin on,” DeConnick writes. The account is honest and raw and as earnest as DeConnick undoubtedly was, back in the days when she walked around everywhere carrying “a notebook and How to Write a Novel in 90 Days, the cover purposefully displayed."

Graham’s contribution is beautiful — just in terms of pure density, nobody draws a more rewarding comics page than Graham, with characters slouching around cityscapes packed with details and wordplay and corny jokes (on one street, a home is marked “Tori’s House,” with a tower down the street labeled as an “Observe a Tori.”) I’m not sure what, exactly, is going on in the story beyond a couple going to a restaurant that only serves whale, but I want to examine these pages, with their diagrams of cups of pudding and digressions about pornographic currency (“barely legal tender,” of course,) until a story makes itself obvious. With Graham’s work, the digging is the treasure.

The final story, a skateboarding (kinda) superhero adventure by an artist named Ludroe, is rougher than all the others — you get the sense that Ludroe is a graffiti artist who hasn’t quite adapted from Sharpies to a more nuanced tool — but it feels like an attempt to create an urban mythology. Maybe if someone tried to invent Marvel Comics in the New York City of today, it would look something like this.

So, yes. There’s no real connective tissue between these stories besides the fact that they appear between the same covers, and Brandon Graham decided to show them to you. Sure, the stories share some artistic flourishes — a European sensibility, a progressive vibrance — but they’re distinct works by distinct artists. Maybe that’s why Island works so well. It doesn’t try too hard to sell an aesthetic beyond pure cartooning ambition. In this case, that’s more than enough of a unifying theme to win my allegiance.