Danielle Dutton’s Paper Bodies

I thought I might go nuts if I read another article about how a woman writer balances her art and family commitments, but Danielle Dutton’s ability to balance multiple projects verges on superhuman. So I had to ask.

Dutton is the founder and publisher of Dorothy, a Publishing Project; a tenure-track professor; author of two novels and a collection of short stories as well as a doting mother with the “best kid ever.” Any of those things taken individually would be enough to keep most people busy, but Dutton seems energized by all of it.

“I’m a Libra, so I think about balance a lot,” she said when she met me for breakfast last week. “But not everything can have my attention all the time. Balance is being able to shift.”

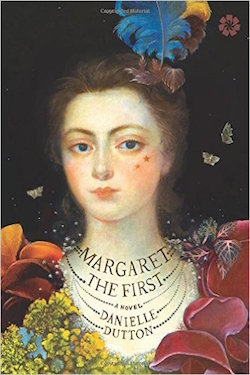

The novel is an exploration of the psyche of an incredibly creative but somewhat suppressed woman. Dutton inhabits Cavendish and gives her an authentic voice. “Hadn’t I thoughts, after all? A mind of my own? It cannot be infamy, I reasoned, to run or seek after glory, to love perfection, desire praise,” she writes in Cavendish’s voice.

Both Dutton and the subject of her novel are women of ambition with unprecedented successes for their time. Cavendish, the historical figure fictionalized in Dutton’s novel, was an aristocratic woman in the 17th century who never bore children, instead devoting herself to writing some of the earliest utopian science fiction. She became the first woman to be allowed entry into the Royal Society of London, an exclusive club of science and philosophers founded by King Charles.

Dutton has built Dorothy, a Publishing Project into a sustainable independent publishing house in an industry dominated by five publishing conglomerates based out of New York. She has also launched her own work — also on a small press — to wide critical acclaim, recently earning two positive reviews in The New York Times.

In the 1600s, it was rare for a woman to be taken seriously as a member of the intellectual elite. Now, it is incredibly unusual for small press books to gain the level of cultural awareness enjoyed by some of Dorothy’s titles and Dutton’s own work.

In 2014, Dorothy published The Wallcreeper by Nell Zink, which was named one of the 100 notable books of the year by The New York Times.

“We had this Jonathan Franzen blurb on the cover, which was kind of curious coming from a feminist micropress,” she said, “And of course we thought the book was amazing, bizarre and hilarious. It had the whole package.” The Wallcreeper had a larger print run than any other Dorothy title and went into two reprints in the first three months after its release. The book offered new financial resources to the press that was already doing well by micro-press standards. Dutton says Dorothy paid for itself within the first year.

“Dorothy sometimes takes over our house,” Dutton said. She and her husband, Marty, run the press out of their home, something that is not unusual for presses this size, but The Wallcreeper quickly outgrew their basement. The Duttons had to work with Small Press Distribution to keep a large quantity of the book on hand, something they do not usually do but was made necessary by the volume and speed of sales.

“We couldn’t have warehoused all the books at our house,” she said. “It was so strange. We’d had other books do well, but this one entered a cultural space that was way beyond Dorothy.”

Zink has since moved on to publish with the much larger Ecco, an imprint of Harper Collins, after being given a six figure advance. Dutton doesn’t have any qualms with that.

“It’s not like I sit down and think, ‘I want to launch someone’s career,’ I just want to publish books that I think are awesome and need to be published,” she said. It is starting to seem normal that her authors get agents after signing with Dorothy, which speaks volumes about Dutton’s taste as an editor.

Despite the success of Dorothy, Dutton and her husband do not plan to expand beyond publishing two titles a year. They want to still be able to give each title the attention it deserves to help shape the work. Now that her book tour is over, Dutton is looking for the next thing to obsess over and write about. Right now, she’s relishing in reading Angela Thurkell, a popular British author from the 1930s.

“I quite like messy writing,” she says. “I’m always looking for some kind of freedom; it’s something I can feel as a reader.” For Dutton, fascination is her freedom and it can be deeply felt in Margaret the First.

Late in Cavendish’s life, a crate containing the sole copies of most of her writings went missing while she was moving across Europe. She had no children and felt that these works — what she called her “paper bodies” — were the only piece of her that would be left when she died. Eventually, the crate made it back to her. Dutton, however, doesn’t have to worry about her work being erased from time.