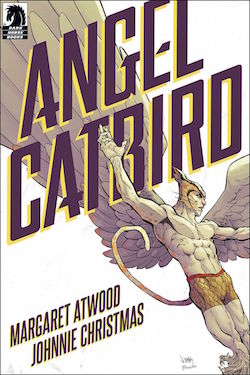

Thursday Comics Hangover: Margaret Atwood's first comic, Angel Catbird, is not very good

Margaret Atwood deserves the Nobel Prize for Literature. She’s written some of the best books written in English over the last fifty years and her range far surpasses most of her American contemporaries, stretching from science fiction to literary fiction and back again. She’s an underrated poet. And she’s terrific on Twitter. So when Portland comics publisher Dark Horse announced that they would be publishing Atwood’s first comic, Angel Catbird, in the fall of 2016, I was understandably excited. The news that Angel Catbird would be drawn by Johnnie Christmas, and up-and-coming comics artist of the Image Comics series Sheltered, made the book sound even more appealing.

Now Angel Catbird is finally on the stands and, uh, well. Even one of the world’s best writers can’t be great at everything. The plot is standard superhero boilerplate: a scientist named Strig Feleedus is working on a miraculous “super-splicer serum” that will cure diseases by “replacing damaged genes with healthy ones.” Feleedus winds up in an accident that splices his genes with that of a cat and an owl, turning him into a human-bird-cat hybrid. Soon, with the help of a secret society of pun-obsessed half-cats, he’s fighting a human-rat hybrid who wants to take over the world or something.

This is not to say that Angel Catbird doesn’t have its moments. A few of the best jokes in the book demonstrate Murakami-level blending of non sequiturs with a painfully dry delivery. (To transform from his catbird form back to human, Feleedus thinks of a washing machine, because “you ever met a cat who likes washing machines?”) But those amusing moments of self-awareness are rare, and buried under metric tons of awkwardness. The love interest is a half-cat named Cate Leone who is in a band called Pussies in Boots who sings songs with lyrics like this: “You are my dish of cream…you are my catnip dream…you are my midnight scream, it’s true.”

In fact, most of Angel Catbird’s troubles are inside the word balloons. The dialogue is wooden and borderline moronic. On the very first page, Feleedus offers a wall of exposition to his housecat:

Don’t want your buddy to be late for his new job! Seeing as I was head-hunted and all—for a top secret project! Very important! I know you don’t like it, but someone’s gotta pay for the cat food!

It’s so clunky and dumb and arrhythmic that it almost feels like an aesthetic attempt toward purposeful artificiality, like the on-the-nose dialogue in a Hal Hartley film. But there’s nothing under the surface to discover, no deeper meaning to the stilted dialogue. It’s just…really bad comics dialogue.

Here’s the villain after he causes the accident that will eventually lead to Angel Catbird’s creation: “Exit Feleedus! My digitally controlled rat slave was the perfect lure! I’ve destroyed the only sample! Tomorrow I’ll grab the formula off his computer! And enter the age of the rat!” So many exclamation points! It's hard to believe an editor allowed this to happen! If the book was even edited at all!

For a few pages, I tricked myself into thinking that perhaps Atwood was writing Angel Catbird for young audiences; the bad dialogue wouldn’t be excusable if that were the case—kids deserve good writing, too—but it would at least be understandable in the context of a clueless adult talking down to kids. But there are too many sex jokes in Angel Catbird for the book to be intended for very young audiences; in the end, I have no idea who this book is supposed to be for, aside from indiscriminate Atwood fans.

At times, and if you look at it from a certain angle, you can see a sort of cheeky old-school comics aura around Angel Catbird. Atwood occasionally sprinkles trivia about cat and songbird wellness throughout the book, which brings to mind the science trivia that used to appear in silver age Flash comics as “Flash Facts.” But if that is, in fact, Atwood’s goal then she’s embracing the wrong traits of old comics — the atrocious dialogue and thought balloons, the facile motivations — and ignoring the vitality that made those books so compelling. In a year that’s seen some excellent mainstream writers successfully make the leap to the world of comics (Ta-Nehisi Coates, William Gibson) Atwood’s first venture into comics is a fairly spectacular failure.