Journey to the heart of the ultimate mean girl

Joan Rivers was one of the most fascinating entertainers of the 20th century. Anyone over the age of 30 can probably tell you something about her life — the way Johnny Carson blacklisted her from his show, for instance, or her QVC shopping empire, or her vicious insults of celebrities, or her catchphrase, "can we talk?" — and every adult under 30 has undoubtedly seen a comedian who was profoundly influenced by Rivers's work.

But there are so many acts to Rivers' life that it's hard to keep track of them all. She climbed to the top of showbiz and fell to the bottom of the heap so often that her life reads like a gaudy amusement park ride. Nobody else danced so eagerly with fame, or was let down by fame's fickle moods so often. You can get whiplash just reading about one of her falls from grace.

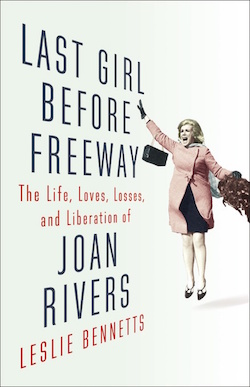

Leslie Bennetts's biography of Rivers, Last Girl Before Freeway: The Life, Loves, Losses, and Liberation of Joan Rivers, provides an eagle-eyed view of Rivers's entire life, and the vistas are breathtaking. Rivers interacted with every major entertainment figure of her time, and she even made an impact outside of the Hollywood bubble: she practically made a career out of mocking first ladies and daughters of presidents. It's a lot to keep track of, and Bennetts does it beautifully.

Thankfully, Bennetts doesn't lose track of Rivers's many contradictions. Rivers built her career like a feminist — she forced her way into a male-dominated field, and she never let those men forget that a woman got more laughs than they did. But she behaved in ways that seemed downright misogynistic: Rivers gloated about the fact that her fortune was built on cruel fat jokes made at Elizabeth Taylor's expense. She continued to mock women throughout her life, including Kristen Stewart, Angelina Jolie, and others.

Bennetts indicates that Rivers was operating from a place of insecurity, a sense that Rivers always wished she was beautiful: "Rivers believed that women were meant to get love through the one irreplaceable asset she lacked, and she never got over the unfairness of being sentenced to a life deprived of the power of physical beauty." It's not a cop-out meant to absolve her of blame: Bennetts doesn't justify Rivers's behavior, she merely observes it.

In the end, Rivers doesn't reconcile her cruelty. Life doesn't work like that. And those contradictions and heartbreaks and triumphs and tragedies make for one of the most entertaining biographies I've read this year.