What Sean Spicer, A Christmas Carol, and Star Wars can teach us about criticism

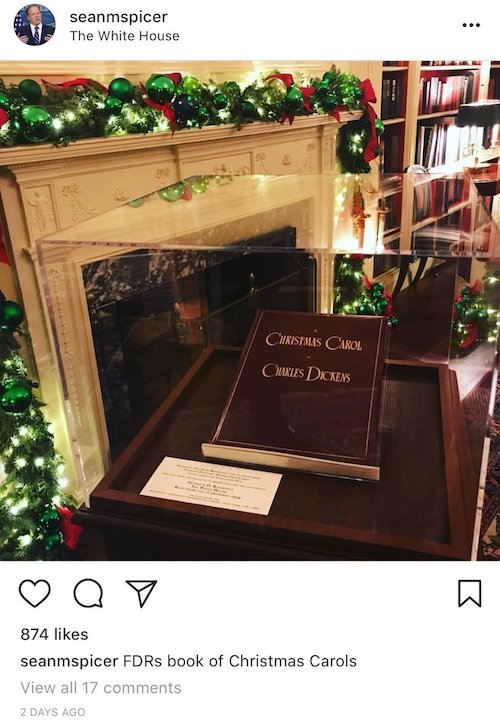

Last week, Sean Spicer posted this unbelievably stupid commentary on Instagram:

Yes, apparently the idiot former White House spokesperson believes that A Christmas Carol is a book of Christmas carols. (The fact that Spicer, after being roundly mocked by the internet for many hours, changed the caption of his Instagram post to read “FDRs [sic] book [sic] of Dicken’s [sic] Christmas Carol [sic]” didn’t much help matters.)

Spicer’s lack of awareness regarding A Christmas Carol reminded me of this blog post from a decade ago arguing that A Christmas Carol is intrinsically a conservative story. One of the main pieces of evidence in favor of A Christmas Carol as a conservative story is that at the end of the story, "The new Scrooge doesn’t run down the street demanding higher tax rates and that the goverment [sic] do more."

I already made fun of this post back in 2008 when it was first published, so I'm not interested in doing that again. In fact, I think about this post a lot. The truth is, A Christmas Carol is not explicitly a progressive text. To mirror the argument made on that conservative film blog, Scrooge doesn’t run down the street demanding stricter regulations of business or a tighter social safety net, either. He runs down the street trying to be a better person. I personally think that the historical record proves that Dickens was more of a progressive author than a conservative one, but A Christmas Carol doesn’t literally contain any political messages that I recall. “Be more charitable with your time, your spirit, and your wealth” is a universal message, not a partisan one.

But that misreading of A Christmas Carol as a conservative text reminds me of the thieves at my bookstore job who used to try to shoplift Batman comics. When I would chase them down and ask them why they were stealing from a small business — something everyone would agree that Batman would frown upon — they convinced themselves that they were freedom fighters, "liberating" the books from the Evil Empire that is an independent bookstore.

You can convince yourself of anything, is what I'm saying. Very few people see themselves as the villains of their own stories. And very few people love stories that they perceive as being outside their belief systems. So we try really hard to squeeze and contort the narratives that we love in order to fit them into our own worldview.

In a lot of ways, the post about the conservative leanings of A Christmas Carol from 2008 that blew my mind was a precursor to fake news, and evangelicals who voted for Roy Moore supposedly for moral reasons. This is not a new thing. But the support network for these political interpretations is much larger, and much more convincing in the age of Facebook. It’s possible to surround yourself with only people who agree with you, and it’s possible to only see the evidence that supports your thesis. And that’s dangerous.

I don’t want to spoil anything for anyone who hasn’t seen The Last Jedi, but the internet is right now full of pissed-off fans — mostly white, mostly male, mostly middle-aged — who argue that the latest Star Wars movie refutes the film franchise’s straight white male roots. Because they’re so used to seeing straight white males as the protagonist of every film they’ve ever seen, these fans don’t have the imagination to see themselves reflected in the latest Star Wars movie, and so they imagine that the movie is attacking their identity.

So while we’re in this cultural moment, I think it’s important to draw the line between criticism and political demagoguery. I’m not saying that criticism isn’t political. In fact, I think all criticism is in one way or another political. But criticism is about what’s on the page — or, in film criticism’s case, what’s on the screen. The angry white male response to Star Wars, like the misreading of A Christmas Carol I linked to above, isn’t based in the text. It’s about manipulating a text to fit into a worldview and to promote an agenda.

I think it’s useful, every so often, to recommit yourself to the text, to reconfirm that the facts we hold dear are in fact true, and to reaffirm that the ground on which you stand is, in fact, solid. If you read fiction to find heroes, and if the heroes in your fiction don’t challenge your worldview in any way, you’re probably reading wrong. If you open every book hoping to find a perfect mirror inside, you’re doing no more work than poor old Sean Spicer, misreading a book’s cover in a futile effort to seem worldly and wise.