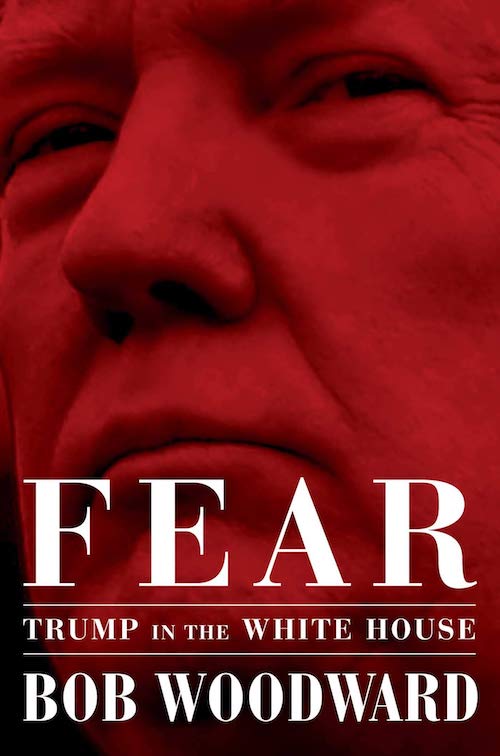

Fear itself

By now, you've read all the salacious excerpts from Bob Woodward's new book Fear: Trump in the White House. Maybe you've found a few of the quotes to be mildly alarming, but I suspect you're not really surprised by anything you've read. Woodward isn't telling us anything new in Fear — we've read about Trump's ineptitude and mediocrity and outright juvenile behavior in the New York Times and in Fire and Fury and in a dozen other places. But none of those other sources carry the same kind of authority as Woodward, who has become the contemporary presidential historian of our time.

What Woodward is providing in Fear, then, is a first draft of history, a record that historians will corroborate or criticize for decades to come. It's an important role, and one that Woodward seems to relish. But you can't really turn to Woodward for good writing — it's remarkable to me that after five decades on the job, he still can't seem to determine the difference between a good sentence and a bad one. And Woodward is primarily interested in the temperament of an administration and the way the primary players interact within the closed system of the White House, not in the results of an administration's policies and its effects on the world.

So Fear reads in some ways like a drawing-room drama, a compact little play with an unbelievable cast of characters, all committing unrealistic actions and saying unintelligent statements to each other. It's easy to forget, in the world as Woodward portrays it, that children are separated from their parents and suffering in camps right now. The book provides very little evidence of the regulatory disasters the Trump administration will cause. Woodward doesn't devote too much time to the enormous payout to the wealthiest Americans that Trump fought for in his first year, instead chronicling the ups and downs of the passage of the tax cuts.

Woodward's Washington is a place where politics is a game of points, with winners and losers, and those results are determined through conventional wisdom. Woodward is interested in which pundits appear on the Sunday morning shows and what they say about his book. He's less interested in the impact these people have on everyday Americans. It's political writing for the sake of politics, not for the sake of the nation.

At this point, I can't make a compelling case why anyone should read these firsthand accounts of day-to-day life in the White House. Does it matter if we know that Trump often doesn't shut off the TV and go to work until 11 am? Do we need another account of Trump lying directly to an aide's face when both men know what the truth is? Why do the specifics matter? Isn't it better to stay focused on the things we can affect in the world, rather than the details of people who don't know our names and don't especially care if we live or die? Why read Fear when it will do nothing to soothe the real fear we feel every day when we wake up and remember who's in charge of the country?