Tricking power into acts of love

—Jackson Fackler, eight years old

The world is very serious right now. And our mature responses to the child who's leading our country don't seem to be making a dent. Maybe it's time to tweak power's nose a bit?

This week's sponsor, Shepherd Siegel, is an award-winning educator and a student of play as a tool for revolution. His new book, Disruptive Play: The Trickster in Politics and Culture, tracks the long history of nose-tweakers and playful rebels who've led social progress in our country and elsewhere. Fittingly, it's a playful book with a weighty message: when you take someone else's power seriously, you give up your own. Read an excerpt on our sponsor feature page for a taste, and then add Siegel's January 8 reading at Third Place Ravenna to your calendar.

Sponsors like Shepherd Seigel make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? There's only ONE slot remaining in our fall/winter block, for the week of January 21. Grab it fast, and be one of the first books (or events) our readers see in 2019! Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from October 15th - October 21st

Monday, October 15: Not Heaven, Somewhere Else Reading

I've already told you why you should read Rebecca Brown’s new collection, Not Heaven, Somewhere Else: A Cycle of Stories. But if you're still not convinced, you should attend this reading, and hear the work in the author's own words. Find out why I am 100 percent positive that Brown is the smartest writer in Seattle — and also find out why she's often the most joyful reader in town on any given night. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, October 16: Ted Chiang and Karen Joy Fowler in Conversation

Everyone should know that Ted Chiang, author of the story that was the basis for the excellent film Arrival, is from the Seattle area. he's one of the best-loved writers within the sci-fi community, and for a great reason: he's smart, he's kind, and he loves to be generous with his knowledge. Tonight, Chiang will be in conversation with nationally loved sci-fi writer Karen Joy Fowler. This should be a sci-fi conversation for the ages. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7 pm, $10.

Wednesday, October 17: WordsWest 38

West Seattle's best reading series continues tonight with a reading along the theme "Girls & Daughters." The readers are a coupling that never occurred to me before, but which makes perfect sense: Stacey Levine and Anca Szilágyi. Levine has been writing and reading in Seattle since the 1990s — she had a single on Sub Pop back in the day — and Szilágyi's work has a fair amount of Levine's DNA in it. This is a fascinating duet. C&P Coffee Co., 5612 California Ave SW, http://wordswestliterary.weebly.com, 7 pm, free.

Thursday, October 18: Walter Mosley

Walter Mosley is an iconic author — one of the few writers left who draw a massive audience on the strength of his name alone. (And he always dresses like a star for his readings.) His latest book, John Woman, is about a man with a mysterious past. Northwest African American Museum, 2300 S Massachusetts St, 518-6000. http://naamnw.org, 7 pm, free.

Friday, October 19: What We Do with the Wreckage Reading

Local author Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum, who contributed to the excellent This Is the Place anthology, reads from her new award-winning short story collection, What We Do with the Wreckage. It's about rising above the horrors of the past. *Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 6 pm, free.

Saturday, October 20: New England Review Anniversary Reading

Okay, obviously the Seattle Review of Books isn't ordinarily the place to celebrate the 40th anniversary of a magazine titled the New England Review, but get a load of the authors who'll be coming to this event: Keetje Kuipers, Eric McMillan, Susan Rich, Rick Barot, Gabrielle Bates, Martha Silano, and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha. We can set aside our famous feud against New England for one afternoon for this lineup. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Sunday, October 21: Killing Marías Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details.

Rainier Arts Center, 3515 S Alaska St, 725-7517, http://www.rainierartscenter.org/, 2 pm, free.

Here are the 2018 Washington State Book Award winners

Over the weekend, The Washington Center for the Book announced this year's Washington State Book Award winners. In case you couldn't make the grand announcement ceremony, here are the winners:

Adult Fiction

This Is How It Always Is by Laurie Frankel, of Seattle

Adult Nonfiction

Mozart's Starling by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, of Seattle

Adult Biography/Memoir

The Spider and the Fly by Claudia Rowe, of Seattle

Poetry

Water & Salt by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, of Redmond

Picture Book

Shawn Loves Sharks by Curtis Manley, of Bellevue, illustrated by Tracy Subisak, of Portland

Books for Young Readers (ages 6 to 8)

Zoey and Sassafras: Dragons and Marshmallows by Asia Citro, of Issaquah

Books for Middle Readers

The Many Reflections of Miss Jane Deming by J. Anderson Coats, of Everett

Books for Young Adult Readers (ages 13 to 18)

The Arsonist by Stephanie Oakes, of Spokane

Congratulations to all the winners, and cheers to everyone who was nominated for the awards this year. And remember: if you published a book this year, submission deadlines for next year's Washington State Book Awards — the first to apply the new qualifications criteria that Susan Rich told you about last week — close on December 1st.

Literary Event of the Week: Staged Reading of Killing Marias at Rainier Arts Center

When it was published last year, I wrote that Washington State Poet Laureate Claudia Castro Luna's new book Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices...

...tries to give voice to the innocent victims of Juarez[, Mexico] — the young women who are killed as a result of the ongoing war of the cartels. Specifically, Castro Luna writes poems about women named María who were killed in Juarez — one poem per victim, with further cues taken from the Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

As I wrote, in Marías Castro Luna serves as "eulogist and a pastor and a biographer and a commentator" for those murdered women, imagining their stories and offering them the dignity of a life that their killers never provided. "She speaks for those who cannot speak," I wrote at the time. "She stands for those women who fell."

Happily, she's still standing. Marías is enjoying a second life. The book has been shortlisted for a Washington State Book Award, and it will be presented as a free staged reading at Rainier Arts Center this Sunday.

With music written and performed by Trio Guadalevín and a dance performance from Milvia Pacheco, this isn't going to be your traditional reading. (Though local writers Donna Miscolta and Catalina Cantú will be unhand to read some of the pieces as well.) This is a multidisciplinary event intended to honor women who lost their lives for no good reason.

This is the kind of event that makes Seattle worthy of the UNESCO title of International City of Literature. It's based on the truth that even a quarter of a world away, even in a world divided by language and culture and politics, we remember. We're witnesses to the lives of those who were lost.

Rainier Arts Center, 3515 S Alaska St, 725-7517, http://www.rainierartscenter.org/, 2 pm, free.

Westwood Village Barnes & Noble to close

West Seattle Blog reports that the Barnes & Noble store in West Seattle is set to close in January. This isn't much of a surprise to people who live in the area: Barnes & Noble is going through a serious downturn and is reassessing all its locations, and the Westwood Village outdoor mall has been plagued with empty spaces for quite some time now.

Still, it's sad that the largest bookstore in West Seattle is shutting down. West Seattleites can still visit the Pegasus Book Exchange, a great used bookstore in the Junction. But as Seattle's traffic woes continue to increase, and as the city prepares to tear the Alaskan Way Viaduct down, West Seattle needs to be more self-sustaining. And every self-sustaining neighborhood neeeds its own bookstore.

West Seattle could absolutely support its own neighborhood bookstore/restaurant combination — something like Ada's Technical Books, or the Third Place Books outposts in Ravenna and Seward Park. (It's worth noting that Third Place Books strongly considered West Seattle as a third location before choosing Seward Park for its latest store.) If you've ever dreamed of opening your own bookstore, I'd say West Seattle is primed and ready for a lively community hub with new books, restaurant, and a full slate of readings and book clubs.

The Sunday Post for October 14, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Going Hungry at the Most Prestigious MFA in America

Katie Prout neatly takes the romance out of “starving writer” with this account of her experience at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop — and Iowa’s food banks. This isn’t a story about sacrificing for your art; it’s a story about the social construct of “the real writer,” and how one university leverages it to its own advantage.

I wondered if I shouldn’t go to the food bank tonight. I thought about all the hours, the days, of not writing, and the shame of it built, but I need to eat, I don’t have a Hadley, which was the name of Hemingway’s second wife, and I don’t have her fortune either, which is how Hemingway was supported during his young years in Paris. In addition to my work with Brian, I’m an instructor at the university where I attend the best nonfiction writing program in the country, and I make approximately $18,000 a year before taxes. When I was denied a second teaching assistantship at the university this summer for the upcoming school year even though I already had signed a contract with the offering department, my director explained that it was in the school’s best interests to look after my best interests, and my best interest was to make sure that I had time write my thesis. Most graduate students are lucky if they get one, it was explained. After, a program-wide email was sent out explaining why the university generally doesn’t allow us to get other university jobs, and encouraging us not to look for any jobs outside of our instructing ones at all.

A Woman, Tree or Not

Terese Marie Mailhot writes eloquently (of course) about the complexities of ceremony, assimilation, and appropriation. “The rhetoric of lost culture is a white imposition” is an incredibly important idea: appropriation isn’t just about naming (ahem) a city’s hockey team “the Totems” — it is as subtle and malignant as declaring, from a position of power, what has been lost, what should be mourned, and even what culture is.

And now, at 35, I am unceremoniously here on staff at Purdue University, an Indian in Indiana without my people. I teach and travel, migrating with semesters. I link myself with other Indigenous communities and speak to people about intergenerational trauma. I explain that what’s been lost is hard to communicate without damaging our psyches or being exploited. It’s hard to not engage in performative measures for white people who might want to grieve us or tour genocide — or save us, or liberate us by bearing witness. I am not a relic, I say over and over at every event as if it were a conjuring, and it is an affirmation.

Daniel Radcliffe and the Art of the Fact-Check

This has been everywhere but is still irresistible fun: Daniel Radcliffe spent a day working in The New Yorker’s fact-checking department to prepare for an upcoming role in The Lifespan of a Fact, a play based on the real-life story of an epic seven-year battle between fact-checker Jim Fingal and author John D’Agata.) Radcliffe takes the job with charming seriousness and a very appropriate humility.

"Hi, Justin. I’m Dan, at The New Yorker," Radcliffe began, twiddling a red pencil. "Some of these questions are going to feel very boring and prosaic to you," he warned. "So bear with me. First off, your surname: is that spelled B-A-Z-D-A-R-I-C-H?" (It is.) "Does the restaurant serve guacamole?" (Yes.) "In the dip itself, would it be right to say there are chilies in adobo and cilantro?" (No adobo, but yes to the cilantro.) "Is there a drink you serve there, a Paloma?" (Yes.) "And that’s pale, pink, and frothy, I believe?" (Correct.) "Is brunch at your place—which, by the way, sounds fantastic—served seven days a week?" (Yes.) "That’s great news," Radcliffe said, "for the accuracy of this, and for me."

Relax, Ladies. Don’t Be So Uptight. You Know You Want It

I’d completely forgotten about that crazy-awful scene from It, the one where “An 11-year-old girl has sex with six boys, one after another!”, which is the point of this essay by Anastasia Basil: when everything is water, you don’t notice that you’re drowning. A revealing tour of the cultural and historic touchpoints in the 80s and 90s that shaped today’s voters, and a critical reminder to keep swimming hard for the surface, even when the waves get big.

Look, I get it. I was 20 years old in 1990. After my boyfriend punched me in the eye, he cried too. I held him until he felt better. I told friends I’d stupidly walked into the corner of an open cabinet. Because, like the Washington Post in 1990, I understood it was my job to help men feel better about themselves. It was my job to understand that their gross, abusive language was just locker room talk. Most men don’t mean to hit us or rape us or verbally abuse us. They don’t really want gay people strung up and hung. It’s just a macho act, you know? Like the Diceman. Besides, if women don’t like that sort of thing, why do they go for guys like that? Or vote them into office? Or make them Supreme Court justices?

Whatcha Reading, Ruth Dickey?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Ruth Dickey is the Executive Director of Seattle Arts & Lectures, an avid reader, an ardent fan of independent bookstores, and an often-procrastinating writer. Fact: this column was largely inspired by receiving emails from Ruth, which include a signature that lists what she's reading, and it is always something compelling.

What are you reading now?

So allow me to begin with a confession: I usually have at least two books I'm reading at once, and sometimes an embarrassingly large stack. I think it's because the amount of things I want to read vastly outpaces what I can actually read. My current two I got in a bookstore at JFK (because a cross country flight without a book is tragic!): Alexandra Fuller's Quiet Until the Thaw, and Ingrid Fetell Less's Joyful: The Surprising Power of Ordinary Things to Create Extraordinary Happiness. I lost my mom five years ago this fall, and she loved Alexandra Fuller's work, so finding this pair of books felt like a special gift at a time when I was particularly thinking of my mom and loss and the funny ways that grief moves through us.

What did you read last?

This summer I had the great gift of walking a chunk of the Northern Route of the Camino de Santiago in Spain, and the last two books I read were both ones I found at the end of my journey: Joanne Harris' Chocolat (in a pizza place in Arzua) and Haruki Murakami's Men Without Women (in a bookstore in Madrid). I love how often books show up in our lives at times we need them, and Harris' story of the triumph of love and compassion over rule and dogma combined with Murakami's haunting stories of people finding their way and the image of a moon made of ice somehow felt like the perfect combination to carry me home.

What are you reading next?

Barbara Kingsolver's new novel, Unsheltered. I absolutely adore Barbara Kingsolver's work, and am looking forward to her new novel and her visit to SAL on October 25th (it's sold out, but we'll be selling standby at the door!). And next in line is another upcoming SAL author I really admire, Valeria Luiselli. I'm looking forward to reading Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions, and to having her at SAL April 17, 2019. Both of these authors tackle issues of justice and compassion and our complicated world in such thoughtful and insightful ways — a perfect balm for these times.

Memorial for Debbie Sarow, October 25

We reported in August that Debbie Sarow, proprietress of Mercer Street Books, had passed away from ovarian cancer. (Martin also wrote a personal reflection on Debbie).

There is to be a memorial service for Debbie at 2pm on October 25th, at St. Paul's Episcopal Church. You can sign up with your email address to be reminded on the Mercer Street Books website. Hope to see you there.

The Help Desk: How do you say "lost in translation" in literally any other language?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Do you speak any other languages? If so, do you read books in other languages?

Either way, do you think that good translations exist? I’m monolingual, but the idea of translating fiction or poetry from one language into another always seemed like doing eye surgery with an old hatchet. I don’t spend much time reading translated stuff because of that, but I always have the nagging sense that I might be missing out on something good.

Pauline, Crown Hill

Dear Pauline,

I've been told my forked tongue is perfect for a particularly dead Latin dialect and I speak French like a child who has no concept of the passage of time. But yes, I do attempt to read books in other languages, mostly crone hexes from the motherland (in my case, Idaho) and the occasional Spanish children's book (I'm trying to use my bad French to teach myself bad Spanish). It took me six months to get through Lucha Libre: The Man in the Silver Mask but I would highly recommend it to anyone who enjoys mask-themed fiction.

I do believe good translations exist – there are multilingual authors who translate their own texts, for example. And as a monolingual reader (or a stumpy trilingual reader, in my case), worrying about what you're missing out on is a bit silly, like refusing to fly Southwest because you'll never grow feathers. Sure the experience is different but it's still a journey. Isn't that the point of a good book and/or economy travel?

If you want to try reading a good translation, the National Book Awards announced just this year a category for translated literature. In fact, Seattle's own Karen Maeda Allman is a judge for that category. Small fuckin' world, right? I'd start there.

Kisses,

Cienna

Lit Crawl proves that Seattle's literary community shows up big in hard times

There's always so much to cover at Lit Crawl. Like last year, we split up. Paul Constant, Martin McClellan, and Dawn McCarra Bass all attended different readings in so we could cover as much as possible. Even with that, we had to make hard choices, and missed things we wish we hadn't. It's not so much about picking your favorite thing as picking the one you'd regret missing the most. But that's just Lit Crawl, isn't it? We wouldn't have it any other way.

Phase 1: 6:00pm

Northwest Literary Survival Kit at Barca

Starting the night with Seattle Public Library's finest felt right — like launching a journey into barely charted lands (okay, from one side of Capitol Hill to the other) with a trusted guide to get you through the first leg.

Northwest Literary Survival Kit, hosted by Andrea Gough and David Wright, promised an orientation to Northwest culture and reading. Note: their real life job is to orient people to books, and Gough serves on the selection committee for Seattle Reads. So, yes, it was a blast.

In a sort of literary fast-pitch. Wright and Gough took turns offering titles from a range of Seattleish themes: local fiction (from No No Boy to Bernadette), Northwest classics ("if you see someone with a Still Life tattoo, you know that what they lack in judgment, they make up in heart"), a hat tip to YA and kidlit (Karen Finneyfrock's Starbird Murphy and the World Outside, among others). Earthquakes, serial killers, Amazon.com. What makes it fun is hearing the two walk through almost thirty titles with footnotes on regional and literary history for each, as only librarians can.

Would we change anything? With all the great readings going on last night, it was a surprise to see only few of the Litcrawl writers' names on the list. But maybe that's trying to improve on perfection — the event is fabulous as is.

The full list should be on the Seattle Public Library site soon, so make sure to check it out. And while you're there, put a few of the last Booktoberfest events on your calendar.

It's Not Right, But It's Okay at Capitol Cider

The best Lit Crawl events tend to have strong themes to tie together disparate authors. And this event had one of the best themes we've seen at a Lit Crawl: Whitney Houston. Poets Elaina Ellis, Amber Flame, and Robert Lashley took turns reading work inspired by or informed by the singer.

Flame said she was enthusiastic to write pieces about Houston last month, but "the world just started fucking burning, right?" In a country that's being ripped apart at its seams, she had a hard time focusing. Ultimately, her work focused on Houston's ability to perform in the face of great adversity. Flame has a magnetic stage presence, allowing her to pull laughs from the darkest comedy. That charisma gave extra emotional power to her tribute to Houston's perseverance.

Lashley's work was full of mourning. He sang praise music like he was holding down the pulpit at a funeral. But he wasn't just saying goodbye to Houston — Lashley was mourning people in his life, and the spirit of cities. His line about "a gentrified funeral march" could just as easily have been about the crowds on the streets of Capitol Hill outside the reading.

Ellis read a very funny piece about mishearing the Houston lyric "I wanna feel the heat with somebody" as "I wanna fall in a heap with somebody." By the end of the night, sitting in a rapt room full of people softly singing the lyrics to "I Wanna Dance with Somebody" through cracking voices, the eulogy widened and grew larger and swallowed everything. The best themes are so specific that they become universal.

Rebecca Brown, Richard Chiem, and JM Miller at Hugo House

The new Hugo House feels ripe with promise. It's like the new pair of sneakers you haven't stepped in mud with, yet. Obviously safer and saner than the last building (the sign on the elevators seen on the opening night “do not use or you will be stuck" is now removed), its theater in the back is a box, and you sit on wheeled chairs on the cement floor. The readers are on a stage with subtly gorgeous lighting splashing faded jewel tones behind them. It's fresh, and different, so confusing, but also quite lovely and an airy, clear place to hear some words

Richard Chiem was first on stage. He read from his upcoming book The King of Joy, of which we're contractually obligated to mention how amazing the cover is [Ed: That's a joke. We are required to disclose there is no contract, but we can also confirm that pretty much everybody here thinks it's quite stunning]. He read in a soft, even voice, the story of his character Corvus. You'll hear much more about her, we suspect, when the novel comes out next year.

JM Miller, next at the podium, acknowledged how difficult the year has been, for the political reality impacting us, and also for them personally. They looked through their last two books and “control f'd how many times I used the word love." Those pieces were then brought together in what they called a “braid of poems" which they read tonight. It was a box of mirrors, fragments and reflections, little turns and larger metaphors. Sometimes hopeful, sometimes calm, sometimes rimmed with rage. “A mountain over you taunts you with horizon," they said at one point, and that line sure stuck.

Last up was the indescribable Rebecca Brown. She mentioned that Richard's work was from a title containing “joy", that JM read about “love", and that her own reading, from her new book Not Heaven, Somewhere Else, contained the word “heaven". Joy, love, and heaven. “Something to move towards besides agony and terror."

The pieces she read from the book — the one that stopped the clocks in the room was “The Girl Who Cried Wolf" — were about agony and terror. Brown has a way of taking a familiar thing and holding it as such an angle that you are convinced you've never seen it before, until she reminds you of all of your associations with it and you are confused as to why you've never seen it like she has before. It's quite a trick. Bless her.

Bless all three of these readers. What a way to start the night.

Phase 2: 7:00pm

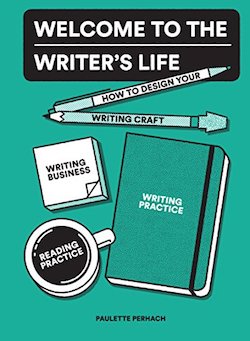

Welcome to the Writers' Life at Roy Street Coffee and TeaTo craft her book Welcome to the Writer's Life, Paulette Perhach interviewed dozens of Seattle writers. In our pre-Crawl conversation with Perhach, she called herself "giddy" after every interview. For Lit Crawl, she brought a few of those writers together: Anca Szilágyi, (author of the fantastic Daughters of the Air, SRoB contributor, and the evening's emcee), Laura Da' (Tributaries, and a new book coming soon), Ross McMeekin (editor of Spartan, author of The Hummingbirds), Geraldine DeRuiter (Everywhereist, All Over the Place), and Perhach herself.

Because this small group meets regularly, the reading felt like an open conversation — like being brought into a group of close friends who're happy to make your acquaintance, which the coffeeshop setting supported. Da' reads almost casually, which lets the natural rhythm of the verse come through, and calmly, which highlights the careful balance between bright and dark that's a trademark of her work ("in the morning, he pronounced the moon both broken and his"). McMeekin read with eyes glued firmly to the page — but it worked, for his essay on the joys of sameness in the writer's daily life.

DeRuiter read a just-finished piece about her accidental Twitter war with her fifth-favorite celebrity crush, Lin Manuel Miranda, who she described as "what you'd get if Kermit the frog wished to be human: giant eyes, beloved by everyone, likely to burst into song." Shame may indeed be "nature's subtle way of letting you know that in a preindustrial society, you'd have been eaten by wolves"; on DeRuiter it's also very, very funny. And Perlach, fittingly, closed the night with the opening from her book: a wonderful bit on grief and fear and making the choice to write, regardless of whether it flies.

This is a great city for writers looking for community — maybe one of the best. If Perlach's book expands that community to a new set of writers, we are all for it.

(By the way, Perhach's essay "A Story of a Fuck Off Fund" is just as smart and biting as ever.)

Women writers on physical and metaphysical, with Sally Heges-Blanquez, Holly Deveboise, Frances Chiem, and Jessica Mooney, at Cafe Solstice

One part of Lit Crawl that you can't get away from: at least one reading in a loud bar that needs a mic. This event found two poets, Sally Heges-Blanquez and Holly Deveboise, and two prose writers working with non-fiction, Frances Chiem and Jessica Mooney.

Sadly, the poets were hard to hear from our vantage point — Heges-Blanquez read short pieces and haikus, and Deveboise, a Made at Hugo House fellow, started by saying “I'm still undecided on what I'm going to read", but that was not a signal she was lost as much as a signal that she knew she'd gain her footing right off. She did, even landing a few good “did she just say what I think she said!?' moments.

“Since I was a teen I've kept a journal of things I would do differently than my mother and father," said Chiem, in a piece that explored intergenerational differences, and what wanting children would even mean to her now. It was a funny and sweet exploration, poking at comfort and discomfort, ease and disease.

Mooney read her piece “Hello, Goodbye", previously published in CityArts Magazine. There are many good lines, and you should take a look, but the one that really picked at the brain was this image:

Fifty years ago, a teenager in China fell for a much older widow. Elders in the village had the same verdict for anyone who fell in love with a cougar: certain death by wrestling an actual cougar. Instead, the couple decided to run away and live in a cave. To help his wife navigate the terrain, the man spent decades hand-carving 6,000 steps into the side of the mountain. But what if she received the effort as a burden, an act of generosity she could never reciprocate? What if all she needed was a zipline?

Jack Straw Poetry Reading at Spin Cycle

Jalayna Carter and Natasha Kochicheril Moni have very different reading styles, but the graduates of the most recent class of Jack Straw's most recent Writers Program shared a special quiet dignity. The Jack Straw program helps writers learn to launch their work from the page into the world of audio, and it was clear that their centered performances came from a place of strength.

"I'm still trying not to get caught in your teeth," Carter read to gasps in the room. Her pronouncement that "you make a mountain out of my heart" caused knees to buckle.

Spin Cycle sells records and CDs, and so Moni's opening statement — "Tonight, I'm going to read you a mixtape" — was deeply venue-appropriate. Her set encompassed road trips and love affairs and unjust police stops and a line from an old poem about the way that poets used to send submissions to magazines in the mail, like love letters. That analog energy, in a room lined with beautiful record sleeves, provided a pleasing comfort.

We've read plenty of poems by Seattle Review of Books contributor Dujie Tahat before, but until last night we hadn't seen him read his work aloud. Wow! Tahat's readings are theatrical, with long, confident pauses and some slippery tongue-twisty gymnastics. On the page, his poems are powerful — he writes about faith and memory and divorce and scripture — but when he reads his work aloud, Tahat controls the heartbeats of everyone in the room. From his visceral older poems to his newer, more playful sestinas, Tahat demonstrated a command of the performing arts that should soon make him one of the hottest tickets in town.

(If you're interested in learning what Jack Straw can do for you, you can apply for this year's Jack Straw Writer's program on their website.)

Phase 3: 8:00pm

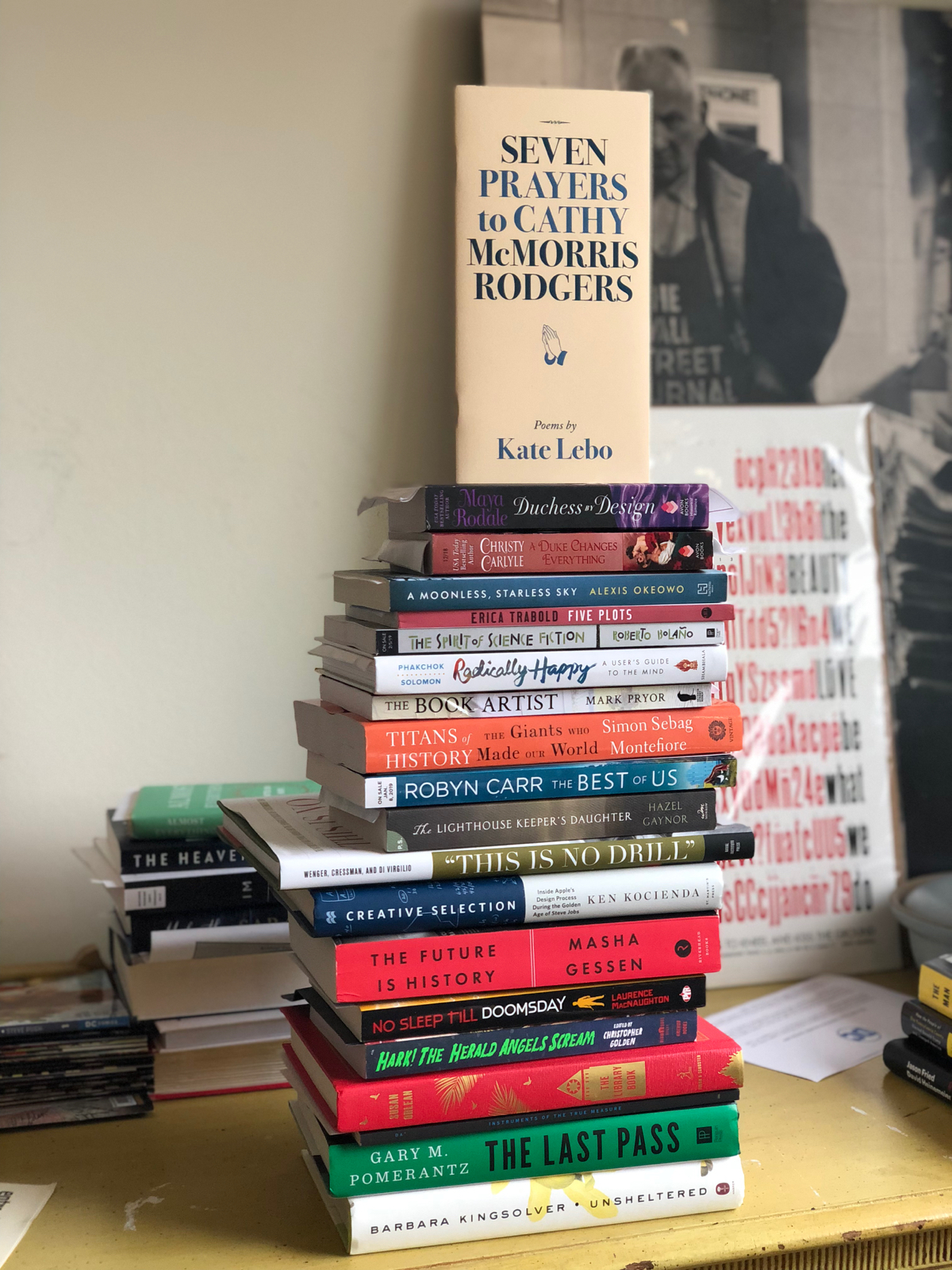

Pie and Whiskey at Capitol Cider

How did pie and whiskey shift from a snack to a book to a movement? Wait — how was the magical combination not a movement from the get-go? Well, anyway. Since 2012, Kate Lebo and Sam Ligon have been stuffing the masses with sugar and booze in service of great readings by great writers. This was a smaller gig than their usual, which boasts upward of 12 readers, 300 listeners, and countless pies and fifths of bourbon. But it was still as close to rock and roll as Lit Crawl gets.

All three readers slammed through their pages, and suddenly you wonder if this is how a reading should always be: fast, loud, funny, the words cascading by so quick you can barely take them in. We heard "vagina," (Lebo's new chapbook Seven Prayers to Cathy McMorris Rodgers) and "massacre" (Ligon's serial novel Miller Kane) fly by in a heartbeat and were swept away with Stacey Levine's rapid-fire short story "Bill Miller." We caught our feet just in time for a low, slow, singsong performance by blues poet Gary Copeland Lilley, which almost silenced the noisy room (almost: this was Pie and Whiskey, after all).

All three of these readers are worth checking out. But note that Lebo is giving her chapbook away free to anyone from the 5th congressional district, so your purchases subsidizes that small act of rebellion.

Then, of course, pie. Capitol Cider surprised Lebo with a gluten-free policy, so she soldiered the crisp, buttery goodness to the patio outside and served up slices to anyone who cared to join her. We did.

Hauntings and Hometowns: A Seattle7 Reading at Corvus & Co.

Frequent Seattle Review of Books contributor Donna Miscolta always creates a strong sense of place in her writing, but the piece she read at Lit Crawl last night was perhaps her strongest geographical work yet. Miscolta's understanding of how people shape place, and vice versa, resulted in a kind of generous, Steinbeckian portrait of a life as viewed through a wise, wide angle. Miscolta shared the stage with Kathleen Alcala, and Alcala's piece about growing up in San Bernadino felt of a pair with Miscolta's fine work. The two read about race and the weight of generations, and how crimes of the past continue to punish innocents in the future.

Jamie Ford's piece bore no similarity that we could discern with Alcala's and Miscolta's pieces, but it was in its own way a show-stopper. Ford shared a story from an upcoming collection about a young girl who develops an imaginary friend, who then tells the girl that she has to kill the president of the United States in order to avert a global catastrophe. It's a killer concept, and while some of the finer points still need some detail work, Ford is clearly enjoying the material, and his lively reading style makes the story all the more enjoyable.

Karen Finneyfrock, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Kamari Bright, and Christine Texeira at Barca

Then we were at Barça, upstairs where it's tight and stuffy. As hostess Karen Finneyfrock pointed out, that's where readings feel most real.

Christine Texeira started with a ghost story, about a ghost and a ghost's ghostly neighbor, and inhabiting a haunted body.

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha read a number of pieces, one an assemblage of thoughts from poets responding to the anniversary of the Nakba, and a newer piece which is in the upcoming Crab Creek Review. Her work has a clear, firm vision, and lovely articulation of cultural placement in society, and geographic cultural uncertainty (that comes through in the piece of hers we published a few years ago, “As in").

Karen Finneyfrock read two poems — she mentioned that she had been writing angry feminist poetry for years, but she's been writing even more lately — that opened with the following lines: "I never had powerful hands", and the second: "I never mistook my grandmother for a wolf." She ended with the essay Strawberry Fields Forever that looks at the intergenerational movement of her maternal line. She looked at how her life differs from that of her great-grandmother, who passed along a piece of wisdom from her long days of migrant labor picking strawberries: "When you are bent over, she said, with your face to the earth, never look up to the end of the row"

Kamari Bright finished the series by standing powerfully in the middle of the room, where the other readers stood in an area demarcated as the stage. She read from a series of works exploring religion and patriarchy. One, titled "The Garden" (published here during her residency in July) flips the origin story of Eden on its head, and imagines Adam as jealous of the snake and apple, his woman stolen by temptation. Kamari is an ambitious multi-disciplinary artist, it is quite easy to imagine the large stages she will someday frequent.

Finneyfrock then sent us on our way, exclaiming that something rare and unprecedented had happened — all poets finished before their allotted time, so we had a bit of extra time to get to our last reading of the night.

Phase 4: 9:00pm

Transformation at Pine Box

Katie Ellison shared a couple pieces from an upcoming memoir about discovering her own Jewishness, and her travels to the Ukraine to learn more about herself. The reading was a perfect capstone to our Lit Crawl experience. Ellison talked about the camaraderie she shared with a stranger sitting next to her on her travels, and recognized the way that even a language barrier couldn't dampen his enthusiasm.

We felt that way on the streets, as we watched people heading to and from readings. We saw plenty of people we recognized, and we noticed some familiar faces have gotten a little older since the first Lit Crawl. Those faces, those other people, are what make a community.

Even if we don't know their names, those people we see populating all the same readings we attend — those are our people. We share a connection with them. Lit Crawl is an opportunity to celebrate that connection, to recognize that though reading and writing are solitary pursuits, those pursuits would be empty without all those other people — not just our contemporaries, but those who came before and those who'll come after. Today, we return to our solitary pursuits. But we're better for knowing that even in our solitude, we are never alone.

An Evening with John Mullen, Elizabeth Austen, Jennie Shortridge at Spin Cycle Records

The ever-delightful Mia Lipman Irwin, host of Lit Fix Seattle, and board member of the Orcas Island Lit Fest, made the intros here, for the last reading of the night.

John Mullen was up first, reading a piece from his memoir, about a boozy, weedy night driving out to find the Suscon Screamer, a ghostly bride still in her wedding whites who haunted the bridge where her brand-new husband had died in a car crash, many years previous. The story was layered, about using anger as a way to get close to people we love (and want to love), and how belief carries you on. Like when his friend tells them to lift their feet off the floorboards going over the bridge, or the bride will make you crash so you can join her in the afterlife. His work is evocative and deftly crafted — his language immediate and skilled, but evoking images he wisely avoids pressing on too hard. He lets the implication float in front of his words like a haunting.

Elizabeth Austen brings the kind of ease and poise to a reading only a Poet Laureate could — that is, someone comfortable standing in front of the room with only a poem or two for protection. By appearance, she teaches a lesson in how to read, how to own your words.

Her works, starting with one titled “How to Vote Like a Girl", were political and pointed, and very much of the moment. She worked on reimagining myths, including (like Kamari Bright, in the previous hour) the story of Adam told anew from a more trustworthy perspective than the man's. After two poems, that imagined a religious vision 15 years apart in their telling (investigating her own personal myths), she read a visceral, immediate, and brutal first-person poem of a rape that was lyrical, beautiful, and heart-rending. It took us all by surprise, and by the throat. Never before has a record store full of people been so silent.

Last up, for the lineup and also for this year's Lit Crawl, was Jennie Shortridge. The founding member of Seattle7Writers read from a piece in progress — something she said she hasn't quite found the form of yet. “It's suicide", she claimed, to read such a thing. (It wasn't).

It began subtly, building on the story of a woman, old and infirm, in body and mind, and her adult daughters holding keepsakes from her life. In a deft weaving, Shortridge builds, step by step, a compelling, difficult story of this mother's rape as a teenager, and its implications that waterfall through her life. One of the keepsakes her daughters hold, as she's dying of emphysema — a hammer — lent Shortridge this perfect closing line to her reading: “What good is a hammer when you're a nail?"

The naked, raw, and impactful truth-telling that Austen and Shortridge brought to their readings underlined that although authors have always dealt with what's current in the world, now there is a willingness to pull absolutely no punches. It wasn't just the words, it was the standing tall and not flinching, not backing down from topics immediate and necessary. The anger, frustration, and dissatisfaction with the current political and cultural landscape means stepping up and speaking a kind of vulnerable, direct truth. There can be no more hiding, and writers like them are on the front of a wave of so many women who are doing the same, or ready to. It's a form of resistance, a potent way to bear witness in the face of those who would sow chaos.

It sounds funny to say, but it is one of the most inspiring and hopeful things witnessed all night. The power from women rising up with real (and honest, if fictional) stories is a catalyst for change. Every time the world changes it's because of stories. By standing up and speaking the message is clear: let us change it again.

Portrait Gallery: Sarah Galvin redux

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Friday, October 12:

Terrible blooms reading

San Francisco writer Melissa Stein’s latest poetry collection, Terrible blooms, was published by Port Townsend’s own Copper Canyon Press. Stein is joined tonight by wondrous Seattle poet Sarah Galvin.

Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Washington State Book Awards to change criteria

In these surreal and brutal times, we need to celebrate one good thing that will affect many writers in our state. As of next year — thanks in part to an essay published right here in the Seattle Review of Books — the guidelines for the Washington State Book Award will change, and simply being born in Washington won’t be enough to qualify an author for the state’s book awards.

Two years ago, I wrote on this site about how the rules of the Washington State Book Award privileged writers born in Washington (and who perhaps left before their first birthday) over writers who live here now. In 2016, half of the poets nominated were not living in Washington State, nor had they lived here recently. At the time of the awards ceremony, the poets were noted as living in Idaho, Missouri, and Tennessee. Carl Phillips, who won the award, had left the state less than a year after his birth. He did not attend the awards ceremony, stating his commitment to a previous travel engagement.

In a turn no one expected, least of all me, this became a hotly contested story. Some writers went out of their way to thank me for voicing concerns that many of us felt privately. A few others felt differently. Linda Andrews, winner of the Washington State Book Award, and judge for 2014–2016, wrote a response to the Seattle Review of Books:

The judging criteria have been in place for 50 years. They have honored many authors who have Washington in their hearts and in their writing. Home stays in the memory powerfully, no matter where the writer wanders.

While this may have a lovely iambic lilt, it seems a sentiment of the nineteenth century more than the twenty-first. The Seattle Review of Books responded to her letter:

A work bearing the honor of Washington State Book Award should reflect the state which granted it such privilege. Why else would we bestow our attention to it? What are we saying by our assignment?

I decided my days as an investigative reporter were over; it was time to return to poetry. To be honest, the entire experience left me profoundly uncomfortable. This was not the Washington poet community that I knew and loved. I tried my best to put the whole experience behind me.

Then a few weeks ago I was asked by Tod Marshall, former Washington State Poet Laureate, to contact Linda Johns, the new coordinator of the Washington Center for the Book concerning Marshall’s beautiful WS129 anthology (in which I have a poem; the book will be honored at the 2018 Washington State Book Awards ceremony, which was the reason for Tod's outreach).

Since Johns is new to the job, I assumed that my critique of the book awards from two years ago would be a non-issue. I was wrong. At the end of Johns’ return email, she writes:

While I have you here, by chance did you notice that we changed the requirements for “Washington author” for the book awards? Being born here isn’t enough of a connection any longer. I thought you might like to know; when my colleague Nono Burling and I took over administrating the Book Awards we looked for ways to make sure that authors have a strong personal connection to Washington. We may refine the criteria again for the next awards cycle (I’m open to suggestions!).

And of course, it’s not the guidelines that determine which books are chosen. It’s the judges that decide the list of finalists and winners. The judges choose books that best exemplify the spirit of our state. For example, this year’s poetry nominees are all current residents of our state. Half of those nominated identify not only as Washingtonian but also as Chilean, Salvadoran, and Palestinian-Jordanian-Syrian.

The new definition of a Washington author is as follows:

- Lived in Washington State as a primary residence for at least five years, or

- Is a current resident and has maintained residence here for at least three years.

I suspect this new definition will provide a stronger focus on the state’s vibrant literary communities. New arts festivals, poetry presses, and reading series are exploding here in Seattle and far beyond. Claudia Castro Luna, the new Washington State Poet Laureate, is the first poet of color appointed to the position. The population of Washington today, is, it’s safe to say, far more diverse than it was even a decade ago.

And while it is true that the guidelines allow for someone who lives here from age 0 to 5 to qualify, or for a student who comes here just to attend college to send their book years later, Johns further explains:

It’s my hope that writers will think of entering the Washington State Book Awards because they have a strong connection to the state, rather than scouting out awards where they qualify on paper, but not in spirit.”

There are 1,001 reasons why so many of us feel frustrated and unheard in the current political climate. Does voicing my support for Dr. Christine Blasey Ford after her historic testimony matter, or my having called Senate offices asking Senators Flake and Collins to vote no on Kavanaugh? In other words, I struggle with the quintessential question: does participating in a public forum make a difference? And if so, how do we know?

In this small but not unimportant detail of how we as a state define our writers, the rules have changed. One article in an online literary review did make a difference. Here’s how we know. Johns again:

I’m appreciative of you questioning the criteria for how an author would qualify for a Washington State Book Award. The article in the Seattle Review of Books and discussion afterwards was a terrific impetus to review everything about the awards. The above criteria are set for the 2019 awards (for books published in 2018; submissions close on December 1, 2018). But we are open to suggestions from writers about future years. And I think that the changes that were made after your SROB pieces show that we’re open to feedback.

It is a rare and beautiful thing to know that one article can make a difference. Maybe I am not done with investigative reporting after all.

Future Alternative Past: Talking Trash

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

A couple of weeks ago, my mother died, suddenly and unexpectedly. Through a fog of grief, I’ve been handling clearing out her apartment; this includes sorting through the material remnants of her life and categorizing them as merchandise versus donations versus garbage. Which is why I’m now thinking about trash in speculative fiction.

It’s a truism that SFFH interrogates basic concepts such as the defining boundaries of consciousness. Also, though, it addresses more mundane issues. Like, what’s garbage? What’s salvage? How can you transform one into the other? And how do the answers to these sorts of questions affect the fictional worlds in which they’re asked?

Inside spaceships and artificial habitats, recycling holds pride of place. Such closed systems must reuse their components indefinitely, breaking them down and reconstituting them ad infinitum. Though I can’t recall which specific stories I first read dealing with this idea (see “fog of grief” above), it’s deeply enough engrained in me that I automatically incorporate it into my own work. “Maggies,” for instance, which first appeared in the second volume of the groundbreaking Dark Matter anthology series, takes place in an off planet underwater terraforming station; in a casual aside I describe a character tossing napkins “into the paper cycler.”

In Dune the fremen of Frank Herbert’s desert planet Arrakis wear “stillsuits,” specially engineered unitards which capture and recycle water normally released via feces, urine, sweat, and exhaled vapors.

William Tenn’s famous “Down among the Dead Men” pushes the conceit of recycling human resources nastily further, positing a future government which not only reclaims used fuels and minerals but reanimates dead soldiers and sends them back into military service.

Nearer to imminent realization is the premise of Ray Bradbury’s 1953 short story “The Garbage Collector,” in which an ordinary man rebels against prosaically horrible instructions for retrieving dead bodies in the event of a nuclear attack. Seattle author Nicola Griffith’s Nebula and Lambda award-winning novel Slow River also hews more closely to current possibilities in its sfnal take on the technology of pollution remediation.

Samuel R. Delany’s Empire Star delivers a bit of Darko Survin's “cognitive estrangement” by showing its characters’ bemusement at our culture’s revulsive reaction to shit — even unto a taboo against talking about it. As one tells another, “food once eaten and passed from the body could not be spoken of by its common name in polite company.” Fantasy sometimes does the opposite, replicating attitudes like these to create bridges between readers and its imaginary worlds. Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside depicts super thief Sancia Grado predictably sneaking toward her target through sewers — but then not-so-predictably, though logically, alerting foes to her presence due to the powerful odor with which said sewers imbue her.

A few SFFH films come to mind, too, touching on this topic. The notorious trash compactor scene in Star Wars: A New Hope ignores the waste-not-want-not ethos mentioned earlier, with our heroes wading ankle deep through smelly chunks of grunge floating in a nameless liquid noxiousness from which the precious water has clearly not been extracted. The outpost dwellers in Kenyan filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu’s short Pumzi deal with their waste very simply, by ejecting it from their doors into the surrounding desert. They do go to great lengths to conserve water, though. And then there’s WALL-E, the 2008 animated movie about a robot trying to clean up an entire planet’s worth of trash. Which we must hope is a completely implausible extrapolation from the worst take on our contemporary garbage-or-not conundrum.

Recent books recently read

Richard K. Morgan’s new cybernoir novel Thin Air (Del Rey) is fat with all kinds of goodness. There’s the exploding-heads-and-voiding-guts sort, the expected excitement of balletic violence depicted with flair, even grace. But there’s also the novel’s wonderfully respectful treatment of its women characters.

With Thin Air’s relentlessly fast action unfolding on a halfway settled Mars only gradually easing back from its frontier attitudes, this is saying something. But though narrator Hakan Veil is a genetically enhanced male, a corporate enforcer permanently stranded far from the green hills of Earth; and though he does plenty of digging to find out how and why mysterious killers are aiming at him, it’s the book’s women who make the crucial difference in this battle between good and evil. The whore next door, the beat-weary detective, the cynical heir of a revolution — all act according to their particular priorities and so further a plot in which more than one gender holds up the paprika-colored Martian sky.

In Red Moon (Orbit), veteran SF author Kim Stanley Robinson once again turns a pragmatic eye on the possibility of colonizing nearby space. He writes with straight-on verisimilitude of China winning the race to lunar domination: their pressurized crawlers scrambling over blazingly white and depthlessly black landscapes, their high-speed trains hurtling along beneath an Earth taking hours to rise apparent inches. China is well established at the Moon’s South Pole, with the U.S. less settled in at the North Pole and struggling to catch up. The enclave of a mysterious billionaire and a utopic socialist community have niches on this satellite as well. But as with Morgan, it’s Robinson’s facility with outsider viewpoints that commands amazed focus. An elderly entertainer, a non-neurotypical quantum engineer, a pregnant labor organizer — Buzz Aldrins they ain’t. Fascinating they are, though, as they wrestle with internal party politics and the almost-offhand destruction of capitalism.

Couple of upcoming cons

Once again the World Fantasy Convention sings its siren song. Guests of Honor from Australia and Paris vouch for WFC’s internationality, and this year’s list of nominees for the prestigious World Fantasy Award presented there is rife with authors outside the dominant demographic paradigm — women, non-gender binary folks, and People of Color. Even at unofficial events such as its “barcon” (a nickname for the daily gathering of geeks in the convention hotel’s bar),World Fantasy’s level of discourse is high. Listen — can you hear its heady call? Answer at will.

Or maybe you’re more drawn to the well-seasoned attractions of Philcon, SFFH’s longest-running convention. The cumulative power of 81 years-worth of panels, writing workshops, masquerades, films, art shows, games, contests, and readings is not to be lightly dismissed. Home to three previous World Science Fiction Conventions (Philcon I, Philcon II, and Millenium Philcon), this is one con that knows its place — not just its geographical location (roughly Philadelphia, if you count New Jersey), but its importance in the genre’s history. This photo of all but one of Philcon’s first attendees says volumes about the future’s past. Attend and you could have something to say about the future’s future.

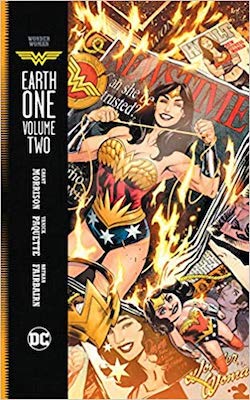

Thursday Comics Hangover: Ban men

All of a sudden, and presumably thanks in part to the smash-hit movie, Wonder Woman comics are exciting again. Seattle author G. Willow Wilson is preparing for a splashy run on the character next month, and even before that announcement, the regular Wonder Woman title saw a notable increase in quality.

And last week, DC Comics published the second volume of their Wonder Woman: Earth One series, written by Grant Morrison, drawn by Yanick Paquette, and colored by Nathan Fairbairn. The Earth One series is intended to provide a new-reader-friendly, straightforward high-quality origin story for DC's most recognizable characters, and it's not even necessary for readers to be familiar with the first volume of the Wonder Woman book to jump into the second.

Paquette and Fairbairn pair seamlessly to make this Wonder Woman visually distinctive. Morrison famously bragged in the round of publicity for the first volume that the book is designed to be almost entirely free of phallic imagery, but Paquette is doing much more than just embracing yonic symbols. Every page of this book is gorgeously designed, with intricate panel borders and involved layouts that still guide the reader across the page. Fairbairn's palette is heavy on regal reds and golds and deep blues — the color of Wonder Woman's costume becomes the basis for her entire world.

The second volume of Wonder Woman: Earth One is very interested in classic superhero comic tropes. The book opens with a flashback to a Nazi superwoman's attempted World War II invasion of Wonder Woman's home, Paradise Island. Rather than imprison the Nazi, the Amazons decide to retrain her into decency, with some rather morally dubious mind-control techniques. This was a common occurrence in pulp fiction like Doc Savage and in early Superman stories, but modern audiences, with a more nuanced understanding of free will, are likely to be creeped out. This is part of the design.

And Wonder Woman herself is trapped in a battle of wills with a pick up artist who wants to dominate her spirit. Morrison blends the traditional (a very straightforward idea of submission and dominance) with the modern (the antagonist is a very Gamergate-style men's rights type.)

This book offers a potent blend of old and new, hopeful and cynical, square and progressive. Like most of the best Wonder Woman comics, it will likely unsettle readers of traditional masculine superhero comics. They'd better get used to it: there are a lot more powerful women coming their way. Personally, I'm excited for some more women-led creative teams to take up the charge.

Book News Roundup: Seattle author lands on Reese Witherspoon's reading list

Seattle author (and former Stranger editor-in-chief) Tricia Romano is writing a biography of the Village Voice. She has encountered a significant amount of tragedy this year and she's looking for some help through a GoFundMe page as she continues to interview people and do research for her book. Consider giving if you can, and if you want to read her book about the storied alternative weekly.

Reese Witherspoon has a book club, and her October book club pick is Seattle author Laurie Frankel's novel This Is How It Always Is, which is a book that I loved. I guess Reese and I are book twinsies?

Y’all. @RWitherspoon’s October pick for #ReesesBookClub is HERE! #ThisIsHowItAlwaysIs by @Laurie_Frankel is a story about family, parenthood, and the love, heartache, and hope that comes with it. Can’t wait to hear what you think! https://t.co/A0ktYtRjwE pic.twitter.com/ulILwylCiI

— Hello Sunshine (@hellosunshine) October 4, 2018

Is someone about to buy Barnes & Noble? Seems like it.

Speaking of Barnes & Noble, here's an infographic they put out that demonstrates political book sales since 2016. I'm pretty sure it doesn't mean anything in particular, but if you're as obsessed with the midterms as I am, you'll probably stare at the map for a few minutes trying to divine understanding from it.

Barnes & Noble says political book sales have skyrocketed and it released a map that shows how polarized the sales are. https://t.co/F9iUWJPxBc pic.twitter.com/shsH5QIuaY

— CNBC (@CNBC) October 9, 2018

If you've spent any time on Twitter over the last few days, you've likely seen a tweet of a MAD Magazine strip that uses the art style of Edward Gorey to comment on school shootings. (We're not sharing the tweet here because it's basically piracy — someone tweeted photographs of the entire strip, meaning readers don't have to go to MAD's site or pick up a copy on newsstands to read it. That's pretty gross.) But you might not know that the artist of that strip is Marc Palm, a Seattle cartoonist who is no stranger to the Seattle Review of Books. And now, the strip is being promoted by the New York Times. Congratulations to Palm for what we hope is the first instance in a long career of going viral.

Paulette Perhach helps you "see behind that curtain of the author photos"

This summer, Seattle author Paulette Perhach published her first book, a how-to-write guide titled Welcome to the Writer's Life. The book is a great practical guide to the craft and business of writing for aspiring authors, and it also serves as a wonderful cross-section of the Seattle writing community. I talked with Perhach about her event at tomorrow's Lit Crawl, what the reception for her book has been like, and what it's like to publish a debut book that's a writing guide. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Before we get into the book, this interview is going to run the day before Lit Crawl, so I wanted to ask what you had planned for your Lit Crawl reading.

I'm going to be gathering writers from my book, Welcome to the Writer's Life. In the book, I interviewed various writers about being writers. So for the reading we've got me, Anca Szilágyi, Laura Da', Ross McMeekin, and Geraldine DeRuiter, which is such a great lineup. It will be really cool to see how everyone will interpret the theme, which is "Welcome to the Writer's Life."

And that segues us neatly to your book! I really enjoyed it — it's got good advice for writers and it's well-written, and it's thoughtful. What is it like putting out a how-to-write book as your first book?

Well, there's different kinds of writing books. There's the "I'm Stephen King and I've obviously mastered this, so here's everything I know" kind of book.

That's not this book.

This book is about how I used to be totally lazy until I realized I was never going to get what I really wanted, which was to be a writer. It's how I changed myself from someone who wanted to be a writer to someone who was working to be a writer and then looked around and realized, I am a writer. It's about making that transition. There's a lot about work habits and about how to really shift your life to go after it if you want to.

It's for people who maybe aren't lucky enough to live in a city like Seattle or who don't have the chance to sit across the table from three or four other writers and just hear them talk about their lives.

It helps people see behind that curtain of the author photos, which makes everyone look official, and see that everyone feels like a fraud. Everyone's scared. Everyone is trying to figure out how to make it work. You just have to dive in and join the party.

I find that writers love to bullshit about writing — they love to make it sound like the worst thing in the world. Did you have to do a certain amount of digging to get through that bullshit with some writers? Was it difficult at all to get them to talk about the actual mechanics of it?

Every writer has no idea how they make art. And yet you can say, "okay, well, when you're feeling self-doubt, what you do?" I got some great nuggets of wisdom from everyone I interviewed. It was really a joy to talk with writers about writing. After every interview, I kind of felt giddy.

It must help that you're in a writer's workshop with all those great writers.

Yeah, we meet every other week. You come, you read your work out loud, and everyone critiques it.

I think my biggest secret is what I call stakeouts. They're fake stakes — an answer to the question "what would happen if I didn't write today?" I have to have an answer to that question: with the workshop, if I don't write regularly, I'm not going to be able to bring something in to this workshop of people that I really respect.

I have kind of an addiction to reading how-to-write books. You mentioned it already, but On Writing by Stephen King is one of my favorites — even though I'm not crazy about the books that he's written over the last, uh, you know, two decades or so. What about you? Do you still read writing guides?

Yeah, I love them. I used to think I had to be self-taught, and there was some pride in that. And then I realized: "Oh yeah, there's instructions, dummy! Just read the instructions." I really love Priscilla Long's The Writer’s Portable Mentor. That was one of my favorites from the get-go. Some of the first books I picked up when I realized I wanted to try to be a writer were Bird By Bird and The Artist's Way.

As someone who was a totally lazy and terrible student who always wanted to buck the system, I thought it was a fun game to try to not be educated. And the day I graduated college I was like, "oh, I'm supposed to be educated now. I did it — I bucked the system, but now I don't know anything."

So I'm going to be a student for the rest of my life trying to make up for what a terrible student I was in high school and college. I'm into learning as much as I can about how it's done, but then at some point you have to put the how-to-write book down and actually write. They can be a form of procrastination.

Did you have a specific reader in mind as you were writing the book?

I guess I was writing to myself at age 28, when I had come back from Peace Corps and knew I wanted to be a creative writer. I had no money, I had a day job and a side gig on the weekends, I had student loans. I would try to write for like an hour in the evening. I wanted to gain some traction, but I had no idea what I was doing. I started submitting immediately, which is so dumb. I wrote my first story and I emailed all my friends to say, like "I've become a writer." I don't want to know how terrible that story probably was.

So the book is for the person who wants to try to start writing but doesn't really have a plan, or know how to prioritize what it takes to be a writer.

How has it been, now that the book is out in the world? Are you finding it difficult to shift gears back into writing about something other than writing?

I decided for myself that I want to be a writer who helps writers. But I still need to make sure that I don't lose that artist part, where it's just for the joy of it. I use my writer's workshop only for my art writing. That's my sacred space.

Bringing it back to Lit Crawl, is there anything that you're looking forward to at Lit Crawl this year?

There's so many things. I usually just let the night wash over me, because it gets to a point where the opportunity cost just weighs on you. I like to think that going to things like this is like walking through the forest. You're not going to see every tree, but the trees that you're going to see are beautiful.

Mail Call for October 9, 2018

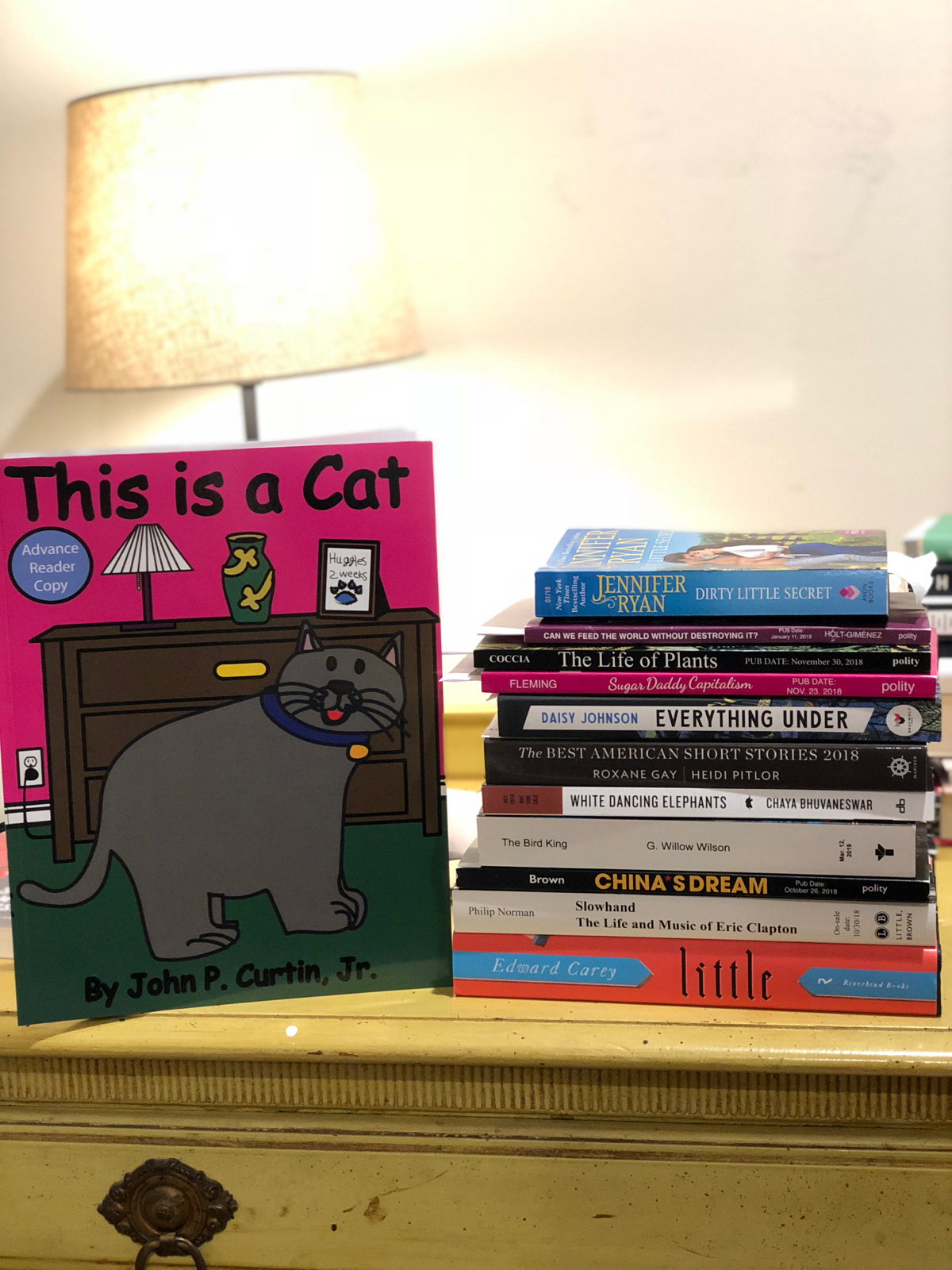

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Mark Ebner's Daily Beast interview with Stan Lee is heartbreaking.

Stan, you’re 95?

STAN: 95.

You’re going to outlive all of us in this room.

STAN: I hope not. I have no desire to.

When I was younger, I disliked Stan Lee. It was fashionable to dislike Stan Lee. And it was morally correct, too — all the artists who worked for Marvel Comics at the beginning were basically screwed out of a lot of money and glory and stability, and some of that is Stan Lee's fault and some of it is general corporate malfeasance. This is a debate that will continue for as long as the Marvel Comics characters continue to dominate the culture. But it's clear to me that nobody deserves to live out their days in the way that Stan Lee has. He's suffered a great deal, and I hope he can find some happiness.