Archives of Interviews

Talking with Madison Books manager James Crossley about opening Seattle's newest bookstore

James Crossely has been a bookseller in the Seattle region for years, at Mercer Island's Island Books. So when Phinney Books owner Tom Nissley announced this fall that Crossley would be managing Madison Books, his new bookstore in Madison Park, the news was greeted by the bookselling community with a great sigh of relief: they knew the store was in good hands.

It's taken a little longer than expected to open Madison Books thanks to a more intense-than-expected construction schedule. But last Monday, Crossley opened the store in a temporary, "pop-up" situation for the holiday season through Christmas Eve, and then on December 27th, 28th, and 29th. We talked to him about how it's been going.

First of all, what's your store's all-time bestselling book?

That's a good question. Right now It's probably a three-way tie between Becoming, Michelle Obama's memoir, Educated by Tara Westover, and Milkman by Anna Burns.

So I guess your clientele is really into one-word titles apparently.

Yes, and that's good to know.

How has running the shop been so far?

It's been great! We've had a really hospitable welcome — a lot of people coming in the store to buy books already ,and even more who just want to stick their heads in the door and say "welcome to the neighborhood."

We're so glad to have a great outpouring of warm wishes. And I've had some unexpected visitors from my bookselling career — people popping up from the past to check out the new operation, which has been great. There's been great support from the from the bookselling community. We got donated shelves from University Book Store. I got help from former coworkers in setting up the space. And also, the publisher reps have been great: they hand-delivered copies of books late in the evening, like, "hey, do you need more copies of this book? I could just bring them by at seven or eight." It's all reaffirmed my continuing belief that this is just a great literary community.

Did you ever visit the bookstore that was in the area years ago?

I did! I used to shop there a little bit. It was called Madison Park Books and it was in a funky triangular space across the street and just just west of us. It was a charming and interesting place. When the store closed, somebody who used to work there went to Island Books and I worked with her for a decade. I think of her a lot as I'm in here now.

Are there any sections that you think you're going to have to refocus on based on consumer demand so far?

I've already got a hint of it. I think I did a pretty good job figuring out what people are interested in, but they are maybe even more interested in the mystery section that I thought they might be. A couple local authors come in asked if we local authors will have a presence here, and of course they will.

Mostly though, I just get the sense that they're so happy to have have a bookstore back on this street.

Do you have a rough opening date in mind after you close the pop-up once the holidays are done?

It looks like right now the end of February or the beginning of March is when all the work will be done and we'll be able to reopen.

Great. This is really an opportunity for people who to come in and sort of help shape the store a little bit, isn't it?

Absolutely. One of the first things we did was hang some butcher paper on the wall and draw some virtual "shelves" with an invitation for people to fill them in with what they want to see — first of all what they want to get under the tree this year, but more importantly what they want to see on our shelves going forward.

And what are your hours right now?

On weekdays and Saturdays, ten to seven. On Sundays, twelve to five.

Okay. Is there anything else that you think that my readers should know about?

I would love them to know that the very first book that we sold was a copy of The Overstory, by Richard Powers, which is one of my favorite books this year. And our first special order has already been placed and arrived, and it was for The Beastie Boys Book. Being able to get those in people's hands was a good feeling. A great feeling.

Laura Da' loves the privacy of writing in public

The poet Laura Da' has been a notable name in Seattle for a good long while now. But a few years ago, it felt like Da' started appearing everywhere. She showed up on bills at group readings, and she appeared as a featured poet at book launch parties, and she taught workshops at the library. Da's ascension into the upper echelon of Seattle's literary scene happened gradually, but once you noticed that she had become an important figure, that realization felt right and good.

As you can see in the poems Da' has published with us as our Poet in Residence for the month of November, she is a meticulous and thoughtful poet. She works frequently with finely wrought couplets, often revolving around a single powerful word or image. A good Da' poem feels to me like a delicate string of glowing pearls, hung on a string of silver so finely crafted that it's almost invisible.

Over coffee, I ask Da' if she agrees with my assessment that she one day seemed to be ubiquitous in Seattle's poetry scene, after years on the edges. "I have a son who is eight now," Da' tells me, "and so there was a good amount of time where I was pretty limited in my ability to be out and about." She also points to the 2015 publication of her first full-length collection, Tributaries, as a moment in which her relationship to the city changed.

"I think that I've always been well connected in the indigenous poetry community," Da' says, "because I started my education at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and there are so many writers who have come out of that school. It's a tight, small community generally speaking, though it's incredibly vast in terms of talent and experience." She felt a part of that community almost immediately.

But even though she was born and raised in the Snoqualmie Valley, and lived most of her life in western Washington, breaking into this city's poetry community took more work. "Seattle is not easy to get in the door, I think, which is really unfortunate," Da' says. She says Seattle's literary community has a fair share of "gatekeepers" who aren't especially good at making new voices feel welcome.

But then "I was a Jack Straw fellow and Hugo House fellow and that really helped me," Da' says. What was it about those two programs that worked for her? "I met a lot of wonderful writers and good friends. I'm fairly introverted and shy, so usually I need an extrovert to sort of adopt me. And that was the way I found a place in the Seattle poetry community."

Da' is not one of those poets who have been writing poetry since she could first pick up a pen. She started at the Institute of American Indian Arts with "an idea that I wanted to be involved in museum studies," but then she met poet Arthur Sze, who was an instructor at the school and "a really incredible poet." His work inspired her. "I was 17 and in college and that's when I started writing poetry. I changed majors almost instantly."

What was it about poetry that spoke to Da'? "I really like the ambiguity of poetry and I also hate to be told what to do, ever. So poetry is really appealing to me," she laughs. And it appeals to her inner introvert because it's "a meditative art that feels nicely private even though it is public. There's an element of privacy that I really like."

When Da' writes a poem, she says, she's "looking at the tiniest little elements and sometimes they seem so discreet — molecular, maybe ,is a better word." She calls her poems "very finely constructed," and as she does so she mimes someone repairing a watch, leaning in close to the table and working with delicate tools to place a gear that's almost invisible to the naked eye. "They've taken me a very long time," she says.

She's very aware of the whole scope of her career, and Da' is always trying to stretch her abilities. "I'm a young writer and I don't want to move into a territory where I no longer feel like I'm an emerging writer." She cites her poem "Centaur Culture" as an attempt to do something new. "I'm trying to challenge myself with more of that sort of lyrical essay or prose-poem kind of work. Anytime I feel more established I always try to shift into something a little different."

Da' is happy with the reception her work has received, but she does think a lot about "how my poetry is categorized. I think that it's limited by mainstream publications' desire to essentialize non-white, non-dominant narratives."

Da' explains, "very often in any review [of my work,] it'll talk about how it's a Shawnee document." That's not inaccurate, of course — "I really appreciate my roots as an indigenous writer. My community is indigenous writers, and that's my most important audience, too."

That said, "I do think the dominant mainstream publication industry is much too apt to want to essentialize my work. And I think that institutional racism still allows people to view it through a lens that makes it lesser." The comments that seem to sting most for her are those reviewers who seem surprised by how finely rendered her poems are, as though indigenous poets can't be watchmakers, too.

"There are so many fantastic indigenous poets," Da' says. "There are so many poets who have been trapped by the institutional racism of publication for so long that to have people still apply that worldview feels really wrong and also sort of infuriating."

The poets who influence Da' range widely in terms of style and background. Da' gushes over poems by Danez Smith, Natalie Diaz, Sherwin Bitsui, and Cassandra Lopez. She speaks again of Sze's "respect for the reader and the reader's ability to handle the ambiguity of the unanswered."

She most likes how you can return to a single poem by Sze "every decade, and the more you've learned, the more the poem sings out to you. It's so admirable to me to create something that is beautiful on the first reading, but rewards every single subsequent reading, too."

Da's so enthusiastic about Sze's writing that she doesn't seem to realize that she could just as easily be describing her own work — these elegant couplets crafted from the smallest and most delicate materials, but which only grow finer with age.

Invented writing systems: Levert Banks and journaling the unfiltered mind

Sometimes the arrangement of coincidence changes a life. Imagine this scene: the flight is in the air, carrying hundreds of souls. In first class, Count Basie, his band is flying coach behind him. He rings the call bell to summon the flight attendant.

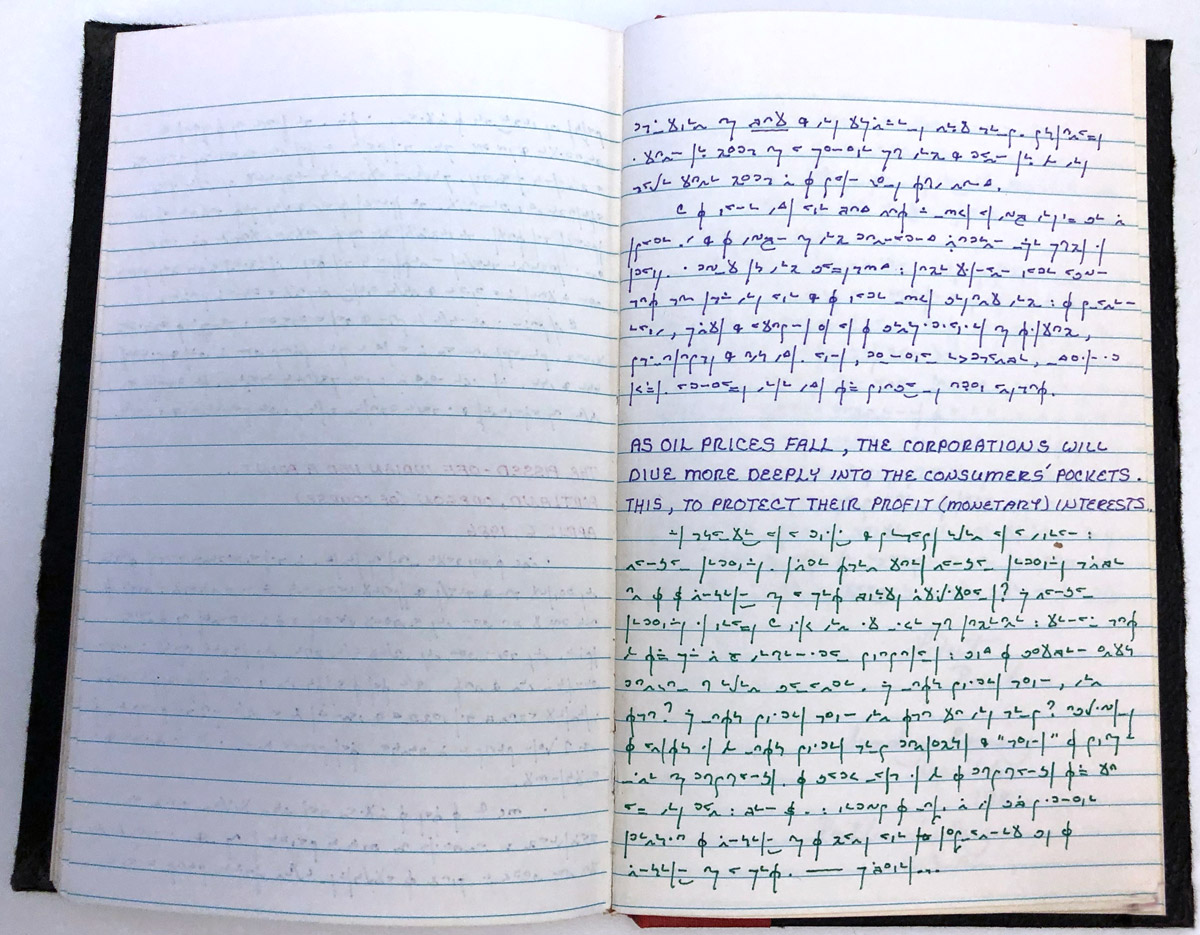

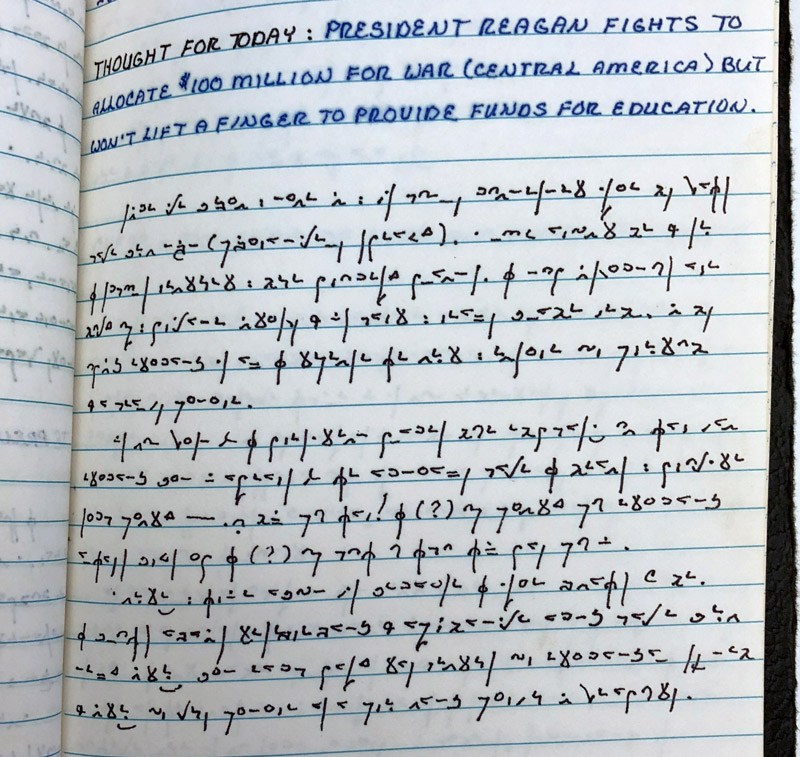

The attendant assigned to him, and who was sitting in the galley, was a young man named Levert Banks. He was writing in his journal when the light came on and he was called to work. Banks had been a daily journaler since being inspired to capture his feelings after the Dallas Cowboys trounced the Broncos in the 1977 season Super Bowl about a decade earlier. It was an epic rivalry, where Roger Staubach demolished former teammate and rival Cowboys' quarterback Craig Morton.

Since then? Banks told me: "I write every day. I don't write well every day, but I write every day. A day doesn't go by when something just erupts."

So he was writing in the back of the plane — on long transcontinental or international flights there was always some downtime to journal — and the buzzer went off. He tucked his book away on a shelf and got up to attend to Basie.

Job handled, Basie sated, Banks was walking back down the aisle when he sees Basie's composer. He had sheet music out and he was composing, right there on the plane, right there on his tray table.

This abstract calligraphy that, for one who knew the method, could make music from marks on paper. What a wonder! "Still, to this day, I've never seen anything as beautiful as someone writing music," Banks said.

Continuing his way through the plane, Banks stopped to chat with another passenger on this flight: Attallah Shabazz, Malcolm X's eldest daughter. She was writing in Arabic, and Banks was taken with the elegance and beauty of the calligraphy. Just the form of the text was gorgeous, like the sheet music. But more than that, it had great meaning to her. "She told me that her father had spoken Arabic and this is the way that she feels connected to him."

"So there's a very personal thing that comes with being able to express what's in your musical head, or your heart of longing, and to do it in a way that a person passing by, like me, just sees it as beautiful and can't really know what it is but knows that it's special."

With those two encounters foremost in his head, Banks returns to the galley at the back of the plane to find his journal being read by his crew. They were reading his most personal thoughts, stories of encounters and people, feelings about his job and his life. It was like they suddenly gained the ability to look into his mind and read him.

"Privacy equals don't let anyone find it. You end up not really writing the way you genuinely feel when you've shielded yourself from incrimination, or whatever else.

"It always frustrated me that being able to write what I really felt, which is the whole point of journaling in my opinion, was restricted by this security issue. So I had spent a lot of effort not letting people find it. You do put it under lock and key, hiding under your mattress."

Diaries have locks for a good reason, after all. Parents, or spouses, read other's journals for good reason, after all, however deceptive the practice — there is no faster way to learn the complex interior of someone else then if they are honest with the page, and you can access it. You either find a way to hide or lock your words up — or, perhaps, you think of a more novel way to disguise your writing.

Because you have to choose: be transparent in the journal and risk being found, or hide yourself from yourself for fear of being found. Banks knew which he would choose:

"The point [of journaling] is that it opens a space in a person as a writer that is so personal. It informs my external world. I seek out relationships where I can have honesty, like can we really just talk here, you and I? I don't know that very many people get to experience that."

So Banks made the choice to start writing in a way that could obscure his words. If Shabazz could do it through Arabic, and Basie's composer could do it through music, maybe Banks could to it, as well. Maybe he could develop a system.

Starting that day, Banks began writing in code.

"It began as a one-to-one connection between random symbols and letters of the alphabet, and then, eventually, I saw vowel groupings, common consonant groupings, articles of speech, conjunctions, prefixes and so forth represented by single unified symbols.

"I wrote all the letters of the alphabet and I erased portions of it. I had to come back and make some refinements because of the physical structure of the way letters are written. I had to make some modifications and different treatments to make sure every character was unique.

"You're going to get tired of writing '-th', or '-ing', or 'the'. Pretty quickly it starts morphing, and a different kind of elegant form comes through. You're like 'okay, maybe I could improve that design a little bit.'

"Now you're back in second grade and it transitions to what is a 't'? What is an 'h'? What is an 'a'? I'm just putting it down because I have an idea. It happens really fast.

"And then when you get to the layer of obfuscation. I tested it with people who said, 'Okay, well, that was something, and this looks like a whatever and that looks like the word blank.

"I go back, machine it a little more and I'm like, “Thank you for that.” I never came back to that same person. I always went to the next person, and over time that's the obfuscation.

"Then, how did I treat double letters? How do I treat numbers? What am I gonna do about punctuation and contractions? Well, I've gotten rid of 99% of all punctuation, you'll never see a question mark."

"Then it said it's finished; like art work, there's a point where the canvas pushes back at the brush and says, 'I'm good.'"

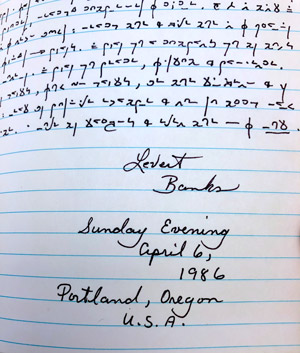

Since that day in 1988, Banks has been writing in, and over the years developing, his created language. He calls it Colan (Koh-lahn), an abbreviation of "coded language". He's taught his grown sons to read it, so that they can have access to his life when he's gone. "Well, I mean, one of my favorite movies of all time is probably Bridges of Madison County," he says.

He's also been going through the thirty years of Colan journals, and the ten that came before that in plain English, and has been working on a memoir.

I asked if he's taught anybody besides his sons to write in his language, and he tells me, no, but he's taught two people how to create their own. I say that my problem with the codes and ciphers I played with as a kid was that I could never remember them.

"Yes, but if you created it, I think, it would have worked. If you have to learn Colan, it might be difficult because you have to learn my rationale or my justification for this or that. But if I taught you how to do it yourself...?"

Colan is a reflection of Levert himself, it has a style and panache that came from his own curious, seeking mind. And it freed him to write his clearest thoughts unfiltered, which allowed him to keep an unexpurgated story of his life. He may not have published, but Banks has written more than most professional published writers.

All because of a chance encounter with Count Basie, his composer, Attallah Shabazz, and some very nosy coworkers, all lined up and flying across the country that one day back in the 80s.

Let an expert bookseller help you give the gift of audiobooks

We are living in a golden age of audiobooks. Freeing audiobooks from physical media, it turns out, is the best thing that ever happened to the medium. Gone are the days with a phlegmatic old man droning through the text of a novel — audiobooks are now finely produced, expertly directed affairs that often add to the narrative in fascinating ways.

But audiobooks are an expensive hobby, and digital audiobooks have been impossible to buy through independent bookstores. Thankfully, the good folks at Seattle-based indie audiobook store Libro.fm teamed up with your favorite independent bookstores to sell audiobooks online and to provide a great subscription membership service.

And now, Libro.fm has made it easy to give audiobooks to your loved ones, with gift memberships and the option to give specific titles as a gift. Best of all, you can support your favorite local bookstore through your gifts. To help you consider your audiobook gift-giving, we talked with Elliott Bay Book Company bookseller and Drunk Booksellers co-host Emma Nichols about good audiobooks to give as gifts.

What's your favorite audiobook of the year?

Circe by Madeline Miller, hands down. It's about the goddess-witch from The Odyssey who turns men into pigs, but Circe is worth listening to whether or not you're interested in mythology or the classics. Miller's novel manages to be both musing and action-packed, and the narrator has the most incredible voice of any audiobook I've listened to — a voice like smoke and cream.

What audio book would you recommend to a teen who doesn't read very much?

Can I say Harry Potter, or is that too obvious? The Jim Dale narration, not the Stephen Fry (not that there's anything wrong with Fry, but I feel like you're either a Fry or a Dale and I'm a Dale.) Second answer: The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making by Cat Valente. It's the story of a young girl who gets spirited off to a place called Fairyland where she has to overthrow a vicious dictator. It has action, humor, and a lot of playful language, which I think is perfect for audio listeners. But what I would tell the teen is that it's about a badass kid who has to make her own way in a magical world.

What non-fiction would you recommend to someone who's looking for escapism?

Shirley Jackson's memoirs Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. Everything coming out right now seems to be about how the world is on fire (figuratively and literally). If you want to get away from politics, climate change, and oppression; if you want to laugh; if you want to be reminded that the image of the chirpy, put-together 50s housewife is total bullshit, read about Jackson's life as a woman, wife, and mother raising four kids in the mid-20th century. It is full of her signature mordant humor. These are the two audiobooks I turn to when I just need a break.

Does book reviewing have a future?

Earlier this fall, I interviewed book critic and author David Ulin at Elliott Bay Book Compahy about his exceptional book The Lost Art of Reading: Books and Resistance in a Troubled Time. We talked about a wide range of subjects, including how we reacted as readers to the election of Donald Trump and whether anyone has written a truly good post-Trump novel. But this excerpt of the discussion, about the future of book reviewing, is particularly relevant to the interests of Seattle Review of Books readers.

Since you have a long and storied history in the field, what do you think is the state of a book reviewing in 2018? Does book reviewing have a future?

Has book reviewing ever had a future?

[Laughs.] Does book reviewing have a past?

I used to joke around when I was doing it for a full-time living that I had unerringly found the lowest-paying, lowest prestige corner of publishing. I had just gravitated right to that, and I was someone who actually — perversely — supported my family as a freelance book reviewer for a long time.

"Supported." I use that word very loosely. When I was freelancing I was reviewing ten or 12 reviews a month because that was my main bread-and-butter gig.

There's two aspects to it, right? With the art of book reviewing, you know that nothing has changed as an abstract. Certainly where it's available and how much it's available has changed. But the inquiry, the essayistic practice and engagement of the writer with a material? I think none of that has necessarily changed.

I think actually in some ways book reviewing or book culture is as robust as it's been in a long time because of the variety of, of web venues that have stepped up. It's impossible to make a living, which is a big problem — the web venues don't pay, or don't pay comparably to the print venues. And the print venues never paid that well to begin with. But I do think there's a lot of places for literary conversation to take place — maybe more places, and certainly more diverse places, than there were ten or 15 or 20 years ago.

I go back and forth on this: I don't miss the gatekeeper model particularly, although I do kind of like the authority of critics. But I think that that authority has to be earned by the critic — not by virtue of who the critic is writing for, but by virtue of what the critic is putting on the page. And so I think if anything has happened is there's more of an onus on the critics to establish their own authority, as opposed to relying on the authority of the institution that they work for.

I think we're clearly getting on about midnight, at this point, for the book review section. But I'm interested as a reader and as a writer in the proliferation of other non-book-review-section-type venues where the conversation can take place.

How Kim Kent is becoming a Seattle poet

Our October poet in residence, Kim Kent, has taken a very long route to arrive at exactly the point where she wanted to be. Kent always considered herself a writer, but she didn't always know that poetry would be her calling.

Growing up in New England, Kent read and wrote fiction. "I wrote a lot of historical fiction as a child," Kent says. "I don't think I had great historical knowledge, so there was always a plague and an enthusiastic, rebellious girl on horseback." Her undergrad minor was in creative writing, but the pull of poetry proved to be unstoppable.

By the time Kent moved to Seattle in 2010, she knew that she wanted to write poetry, but she was having trouble getting motivated. That all changed when she discovered the Hugo House and started to take poetry course. "I think the first class I took was with Kary Wayson," she says, and pauses. "Though it might've been Kate Lebo."

In any case, Wayson's yearlong intensive poetry class proved to be a breakthrough for Kent. "It was intense. She's a great teacher — she's very honest, and for me it was the first time I talked about revision and craft." Kent says the class was "super-generative" and it served as "an introduction to Seattle's literary scene," introducing her to local figures like Kevin Craft.

Kent's poetry is durable — it's constructed thoughtfully and it stays with you. The imagery in her poems resonate in your mind long after you've looked away. Many poets are good at creating one solid moment in their poems. Other poets have a gift for inspiring emotion. Kent's poems do both at once: she sets a scene with clarity and precision, but she also leaves a door open for ambiguity's sake. There's always an unanswered question, an unexplored path, just begging for your attention.

After finding her way around Seattle's literary scene and starting to develop her voice, Kent left Seattle to attend grad school in Spokane from 2015 to 2017. She's a rare Washington poet who's conversant with the literary scene on both sides of the mountains. "For whatever reason, each side of the state has their own opinions of each other, but I felt very lucky to have a home in both."

In recent years, Seattle poets have left town due to rising rents and moved to Spokane. Now, those writers are coming back to visit with surprising regularity. "I went to readings at the Hugo House on Wednesday and Thursday of last week," Kent says, "and both of them had Spokane poets in them. I think the more we can combine our scenes, the better."

That said, Kent feels like she's at home in Seattle. She likes how Seattle's scene "seems very authentic to the city. I like that people are hustling, and even though it isn't always easy, people are showing up for each other and supporting each other more and more."

One of the ways that Kent is showing up for the community is her acceptance into the Made at Hugo program, which provides young Seattle writers with a peer group and a run of the writing organization's resources. Kent is making the most her time as a Made at Hugo Fellow, attending plenty of readings and classes. Right now she's a part of a class by local author Keetje J. Kuipers, which she says offers plenty of new perspectives in a workshop setting. At the end of the program next year, Kent hopes to have a good draft of a first poetry collection to send out to publishers.

Kent seems to be learning as much as she can from a great tradition of Seattle poets. She counts Elizabeth Austen's class about public speaking as one of the most influential learning experiences of her life as a poet, and she's a big fan of Frances McCue's most recent collection. As she talks about her past and her plans, it's clear that she's very deliberate in her intent to place herself in the Northwest poetic tradition. She's proceeding thoughtfully and with great care to ensure that she's adding something of great value to our community.

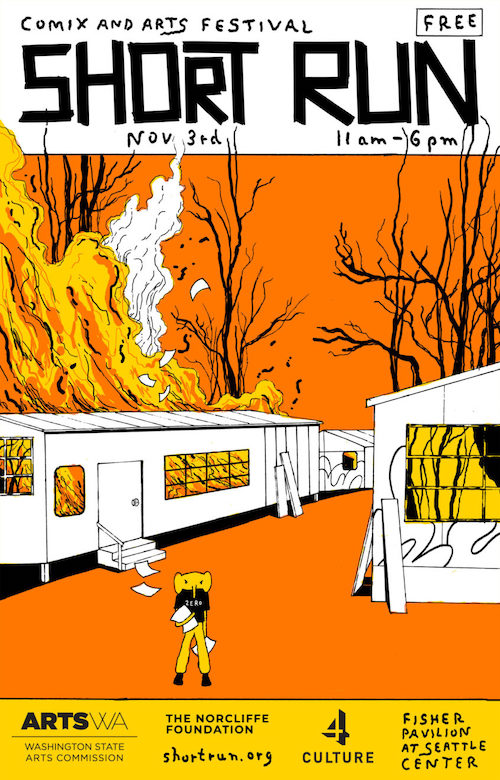

Short Run's biggest self-described "fanboy" is ready to help guide the festival into the future

Earlier today, we published interviews with Short Run board members Megan Kelso and Mita Mahato.Our final Short Run interviewee of the day, Otts Bolisay, is the newest member of Short Run's board, but his enthusiasm for the organization is palpable.

How did you get involved with the Short Run board of directors?

[Short Run cofounder] Kelly [Froh] invited me last year. I had been a Short Run fanboy for a pretty long time — I had gone to, I think, every single one of their summer school classes. I'd been to the programming that they have around the Festival every year. They brought Anders Nilson in one year to speak at Ada's on Capitol Hill. I hadn't really known his work, but even to hear their introduction, and why they thought he was an interesting artist and why they even bought him out to Seattle was just really great. I didn't know any of that stuff. I'd even volunteered at the festival — I screenprinted shirts and everything. I think all that showed I would actually show up and that I was interested.

Why you in particular? What do you think you bring to it?

You know, it's funny: I actually told Kelly that I didn't think I should be on the board because one of the things that I appreciated about Short Run is it was so very distinctly led by women, and that fact showed up in all sorts of ways that I appreciated in the programming. Just everything about Short Run was welcoming and open and it had really different energy. And I appreciated that and I didn't want to mess that up.

So what did Kelly say in response to that?

She said, "no, it's still women-led because I'm here." And I think she knew my background in communications, working especially with nonprofits — she may have had some of that in mind, and some of my relationships that I've had over the years with communities of color. I've done a lot of social change work, and that might have been something that she was hoping I could also bring to the board.

So what have you been doing? What have you been up to?

Well, leading up to the festival, we were just talking about the kinds of programming we wanted, who we could get, who might be a good person to do [onstage] interviews and things like that. And as we get closer, it's more festival business, just the day-to-day of the organization: making sure that there's money, that we don't have to scramble for anything, that we are able to pay people.

I send out the few emails that the organization sends out — reminding people that the festival's coming up, or contacting all the exhibitors with the instructions for Fisher Pavillion, and updating the website.

And as a self described Short Run fanboy, what are you looking forward to in this year's festival?

A coworker of mine sent me an illustration that somebody named Myra Lara, did and it was really cool. And I checked out Myra's website and I realized Myra is one of our exhibitors, and she's also local. Myra is one of the people I'm really looking forward to seeing. I'm also excited for something called Free Ass. Mag. Anders Nilsen is going to be back. i think he's going to have the second part of Tongues with him. I bought the first part last year and I loved it. I'm looking forward to picking that up.

And then I'm excited about yəhaw̓, an indigenous regional indigenous creative group. They've got a bunch of events over the course of the next year, but they're going to be tabling as well. I'm super excited to see what they have.

Megan Kelso is helping Short Run find the ground between "institution" and "crazy young upstart"

Anyone who has spent any amount of time reading Seattle comics knows the name Megan Kelso. Kelso has long been a passionate advocate of the Seattle comics scene, but this year is her first as a full-time member of the board of the Short Run Comix and Arts Festival. We talked about the board's work this year of institutionalizing Short Run without losing any of the special sauce that makes it so great. (Read our interview with Short Run chair Mita Mahato here.)

How did you get involved with the Short Run board of directors?

I met Kelly right after I moved back to Seattle after being away in New York for years. I moved back in 2007 and I met Kelly soon after that at comics events, and then Short Run started up soon after that. I remember her contacting me before the first Short Run and saying something like, "please support us by getting a table — we want as many longtime Seattle cartoonists to participate as possible."

And I was just so thrilled that like a thing like Short Run was starting in Seattle, because for all the comics we have going on here, there had never been much of a show. So I was really enthusiastic from the very beginning. I didn't have a table every single year, but I tried to be involved in some way every year.

To be honest, I wasn't like a super-involved volunteer. I would, you know, put up posters, or sometimes I would host artists who were visiting from out of town. But I always tried to keep my hand in.

And then I also have this other relationship with Kelly, because she looks after elderly people — she's a companion to them, and keeps them company. And she worked for my mom for years. So we, we grew kind of close through that, which had nothing to do with Short Run, but I think we developed this whole working relationship because of that. And in a way I feel like that's partly why she invited me on the board — she got to know me in this other way that showed I was a reliable person in a non-comics context. Then I had more time after my mom died, and Kelly knew that, so that's when she swooped in and asked me to become a more involved Short Run helper.

I was thrilled because I had been keeping my distance a little bit. I just didn't have the time for a few years, because things were really heavy going with my mom. But then my time freed up.

I think I'm the oldest person on the board. And I think that's partly why I'm there too, is I'm a sort of connection to like the comic scene of years past.

So what has it been like, putting the show together from your perspective?

We started meeting in January or February, I think. And, you know, Kelly was really frank with us from the very beginning that she was going to need more help from the board than years past because she didn't have her partner, Eroyn. They kind of invented Short Run out of whole cloth, and they had a lot of it in their heads. So a lot of what Kelly had to do was put more down on paper and put more out for us to do, because she knew she couldn't do it alone.

So I think a lot of this year has been us helping Kelly download everything about Short Run that's been in her brain. I'm getting it more documented so that we can take a lot of it on.

It's an interesting process at the beginning of the year. It's super pie-in-the-sky — we're talking about our hopes and dreams for the next year for the show. And then as time marches on, things just get much more practical: "who's going to pick up this artist at the airport, and who's going to follow up with that person to see if we can get some publicity?"

So, yeah. I have a much better picture now about the yearly cycle of Short Run.

There's been this thread running through the year that we want to make the show more appealing to families with children. We also want to include more people of color both as artists but also as people who help with the festival and, ultimately, work on the board. We've been talking a lot about opening up Short Run to be more than just the traditional comics community that we've had in Seattle over the years — a community which is awesome and who we love. But we also want to open up Short Run to a wider world of people, especially since Seattle's growing so much right now.

Is there anything in particular that you're especially looking forward to this year that you want our readers to know about?

I'm really excited about the artist Anna Haifisch, who drew our poster. I wasn't familiar with her work until Kelly introduced us to it. I think it's one of the coolest posters we've ever had — we've all talked about how it feels timely, like we do feel like the world is on fire right now, and that's kind of been a sort of running theme as we've been planning. So I'm really looking forward to meeting her and seeing more of her work.

And then the other one that I'm, excited about is Rina Ayuyang. I'm actually going to be interviewing her onstage, and I'm excited about it because we've been cartoonist friends-slash-colleagues for years and we've always had a lot to talk about. So I think it'll be kind of really fun for us to do that in this public way. She has this awesome new book from Drawn and Quarterly called Blame This On the Boogie which is all about her obsession with dance movies and dance reality shows. It's just this crazy kind of all-over-the-map book, and I really love it.

Is there anything else that you think that our readers should know before before Short Run really gets underway?

One of the things that I've been thinking about and talking to Kelly about is that this is Short Run's eighth year, and I was imagining a teenager who loves Short Run, who kind of grew up going to Short Run. For that person, Short Run is this institution. Even though we still think of ourselves as this kind of crazy upstart project, I think we're starting to be viewed from the outside as more of an institution. That's an interesting place to be — you have to reconcile your inner feelings of "oh, we're just putting on this crazy show" with the expectations that people have because it's been around for a while now.

Invaded Life Forms: Talking with Calvin Gimpelevich

I once read a very woo book that said our spirits were fifty feet tall and part of the awkwardness of being a baby is that we are crammed into these tiny bodies. Readers can feel the immensity of Calvin Gimpelevich’s spirit unfurl in his writing as he captures the absurdity of being in a body on this planet in a society that continually attempts to restrict our possibilities.

Calvin has been organizing art shows and performances in Seattle with the queer art collective Lion’s Main for years, and his debut collection of stories has been a long time coming. Invasions (Instar Books, October 2018) brings the lens of queer and trans fiction and flips the script on the "real world." The stories in this collection capture the isolation of being in a body in a world where what you appear as determines the limits of who you are. A six-year-old girl wakes up as a middle-aged man; a narrator becomes trapped in the minds of other people; other characters swap bodies only to long for their own somatic memory.

In a time when toxic masculinity is under speculation, and the #MeToo movement is embroiled in who gets to claim it, the gender outlaws in Invasions lead us into the deeper explorations of these power dynamics through a different collateral of social power and powerlessness.

In preparation for his book release at Elliott Bay Book Company on October 28, we spent some time discussing speculative fiction, structure, and the possibility of the body. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

These stories exist at the intersection of speculative fiction and realism. It’s almost as if you’ve warped which is which. We are invaders in these bodies and trying to sort out how to make the shape connect more and are trapped in how other people see us. Is this accurate in your experience of writing these stories? Can you talk about your process of blending realism and speculative fiction?

I lived for many years with my grandmother, who was schizophrenic (my mother being her legal guardian). I remember so many instances of failed communication in which we were unable to move beyond fundamental disagreement of fact. This failure seeped into my adult life, where — both professionally and personally — I've been around many people whose sense of reality doesn't match mine, and where I've realized that my own reality is not necessarily objectively true. I feel best about an interaction, not when I've managed to convince someone that my perspective is right, but when multiple perspectives are allowed to exist, showing what is unseen in our own. The traditional concerns of literary fiction (which I tend to think of as focusing on internal, as opposed to external, action) are almost always more interesting to me, but I've found it natural to dip into speculative work to explore those concerns.

So is it almost like speculative fiction makes it possible for multiple perspectives to exist. Who are some of the writers who helped form this craft approach for you?

Rushdie talks about magical realism as being as legitimate (or accurate — I don't remember the specific wording) as realism, that there is a tyranny in only one accepted perception of fact. I've gotten a lot out of surrealists and magical realists: Allende, Calvino, Morrison, Kafka, Bolaño. Kundera's Unbearable Lightness of Being is still one of the most beautiful perspectives on multiple realities that I've read.

Something the stories truly captured for me was dysphoria — I don’t think I had seen my own experience of it manipulated so well in literature. Particularly the strangeness of being in these heaps of flesh. In "Transmogrification," a story told in the second person, a six-year-old girl wakes up as a middle-aged man. The stories and the narrations get inside my body and take over. How do you see POV at work in your stories to create this effect?

“Transmogrification” is the first short story I wrote (after an attempted novel in high school). I was eighteen — two years from realizing I was trans. At that point, I was so alienated from (and confused by) my own body, that second person — the disorientation of it — seemed better.

You mentioned, earlier, being trapped in how other people see us. Personally, that was as large a piece of my own dysphoria as the physical reality of my body before hormones.

Your stories often seem to start and end in the middle, which I think is a more accurate experience of storytelling. It's also true in the way we think about transitioning in the body. I think a cis audience might think that there is a narrative: gender discovery, hormones, surgery, FIN but it never or very rarely ties up that way. The narrator in your story "Runaways" wonders what's next when he's finally done saving for surgery. How do you find endings in situations and stories where it is philosophically impossible to locate them?

I got obsessively interested in narrative structure in my early twenties, which led to a lot of research, and a drafting process for my own work involving diagrams, numbers, and graphs. I've calmed down (until I teach or edit for other people, which always turns into a rant about five-act structure and kishotenketsu and other things you probably don't need to know, but that I can't stop fixating on). The boring answer is that the endings come out of my personal understanding of narrative and what the central conflict or story is.

Get nerdy! How are five-act structures and kishotenketsu at work in your thinking with Invasions?

Five-act structure is something I've seen discussed more in film and theater than literature, but I've found it helpful in pacing, character motion, and decisions about events. I use it is to imagine the short story as a single act in a larger five-act piece — like pulling a short film out of a longer movie. Vonnegut talks about something similar, and I think it helps make a short seem like part of a larger dynamic world. The best concise overview that I've found of five-act structure is "The Myth of the 3 Act Structure" by Film Critic Hulk. I make all my students read it.

Kishokentetsu is the Japanese name for an East Asian narrative (and argumentative) structure that places the emphasis on contrast as a means of interest, versus conflict (which is often seen as the only legitimate motion in Western narrative tradition — going back to Greek theater). I've read as much as I could about this structure in an attempt to deconstruct the three- and five-act models I've so thoroughly internalized. I haven't drafted anything purely along the lines of this structure (and doubt I grasp it well enough to succeed), but thinking about it has helped bring certain pieces more depth.

Can you talk about the process of writing "The Sweetness" — about a man whose consciousness can enter into the minds of others through their eyes, and ultimately enters into a cop during a gay bathhouse raid? What is your relationship as a writer to entering into other bodies and experiences? How often do you find softness there?

Empathy! This seems like the whole point of being a writer (or a fiction writer), to step into other people with as much softness and suspended judgment as you can. If I were actually psychic, I wouldn't need to write. But I'm not, so I have to construct other internal realities of my own.

I need to shout out my editor Jeanne who invested a lot in this story, and worked particularly closely with me in the editing process. I drafted "The Sweetness" during a painful breakup, which maybe accounts for the tone. See how melodramatic I am? To express my grief at a relationship ending, I wrote a story where everyone dies. It takes place during "Operation Soap," the actual 1980s Toronto bath raids. Here I was also melodramatic — no one died in any fires in the accounts that I read.

That's so interesting, because the fact of everyone dying really highlighted what's at stake in terms of connection, shame, and human frailty. Especially in the present day, when HIV is still an opportunity for criminalization and of course the criminalization of trans bodies, especially the bodies of trans people of color.

Anything set in the 1980s, especially concerning queer people, makes me think about AIDS. It was hovering in my mind in this story — that the epidemic had such a frighteningly deadly rate, so little understanding, and how hard people were fighting to make their governments care. That Operation Soap–like raids were happening in the midst of this, and that the virus is still used as a means of criminalization, is upsetting. I was just reading Samuel R. Delany's letters from 1986. He talks about AIDS so rarely, but it's always hovering. There is a beautiful letter, toward the end, where he talks about moving out of that fear.

While reading I really felt the isolation of the body and the radical potential of it. In “Eternal Boy” the narrator says “I have emotions I just don’t like to feel them.” Characters continually experience the disconnect between what the body is capable of feeling and what they (their spirit, their psyche, whatever it is that fills these forms) are willing to attempt within those limitations. The stories seem to demand, of course you love, but how much are you willing to feel?

Before writing, I studied psychology, and my patchy professional background centers around social work. What you've just said — the disconnect between what the body is capable of feeling and what they are willing to attempt within those limitations — is one of the best summations of what interested me in that field. Trauma is given, but how does a person respond?

In your stories, they seem to respond through isolation or finding connection. Your stories really capture what's at stake in our loneliness.

Yes — isolation and connection not only in relation to other people, but in themselves.

The conflict in many of these stories is the absence of communal care or the desire for it. What is your relationship to communal care in trans and queer lives and TQ literature? Where do you see possibility, and how can fiction take us there?

It's been interesting to see the response to Invasions, which is overwhelmingly focused on the book as a piece of trans literature. I wrote these stories through my transition, living primarily in queer world. To me, I was writing fiction about people, and the people I was around were queer, so it made sense to explore larger topics through them. I understand that I am writing queer lit, but that's not what I'm thinking about when I work.

I suppose that's what any kind of "fill in the blank" literature is — writing about the worlds that we live in.

Who you are will come through.

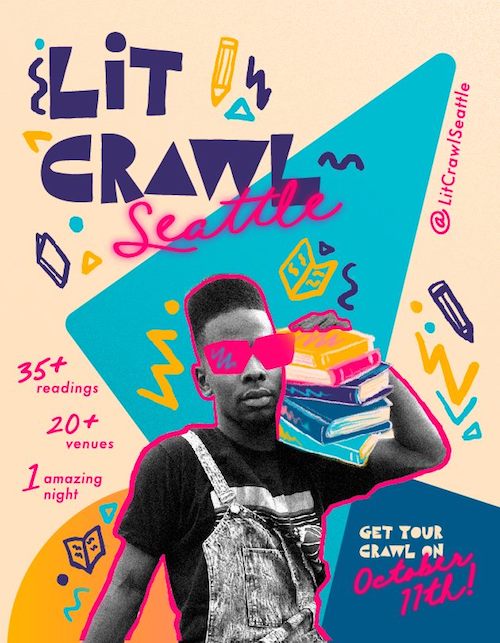

Paulette Perhach helps you "see behind that curtain of the author photos"

This summer, Seattle author Paulette Perhach published her first book, a how-to-write guide titled Welcome to the Writer's Life. The book is a great practical guide to the craft and business of writing for aspiring authors, and it also serves as a wonderful cross-section of the Seattle writing community. I talked with Perhach about her event at tomorrow's Lit Crawl, what the reception for her book has been like, and what it's like to publish a debut book that's a writing guide. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Before we get into the book, this interview is going to run the day before Lit Crawl, so I wanted to ask what you had planned for your Lit Crawl reading.

I'm going to be gathering writers from my book, Welcome to the Writer's Life. In the book, I interviewed various writers about being writers. So for the reading we've got me, Anca Szilágyi, Laura Da', Ross McMeekin, and Geraldine DeRuiter, which is such a great lineup. It will be really cool to see how everyone will interpret the theme, which is "Welcome to the Writer's Life."

And that segues us neatly to your book! I really enjoyed it — it's got good advice for writers and it's well-written, and it's thoughtful. What is it like putting out a how-to-write book as your first book?

Well, there's different kinds of writing books. There's the "I'm Stephen King and I've obviously mastered this, so here's everything I know" kind of book.

That's not this book.

This book is about how I used to be totally lazy until I realized I was never going to get what I really wanted, which was to be a writer. It's how I changed myself from someone who wanted to be a writer to someone who was working to be a writer and then looked around and realized, I am a writer. It's about making that transition. There's a lot about work habits and about how to really shift your life to go after it if you want to.

It's for people who maybe aren't lucky enough to live in a city like Seattle or who don't have the chance to sit across the table from three or four other writers and just hear them talk about their lives.

It helps people see behind that curtain of the author photos, which makes everyone look official, and see that everyone feels like a fraud. Everyone's scared. Everyone is trying to figure out how to make it work. You just have to dive in and join the party.

I find that writers love to bullshit about writing — they love to make it sound like the worst thing in the world. Did you have to do a certain amount of digging to get through that bullshit with some writers? Was it difficult at all to get them to talk about the actual mechanics of it?

Every writer has no idea how they make art. And yet you can say, "okay, well, when you're feeling self-doubt, what you do?" I got some great nuggets of wisdom from everyone I interviewed. It was really a joy to talk with writers about writing. After every interview, I kind of felt giddy.

It must help that you're in a writer's workshop with all those great writers.

Yeah, we meet every other week. You come, you read your work out loud, and everyone critiques it.

I think my biggest secret is what I call stakeouts. They're fake stakes — an answer to the question "what would happen if I didn't write today?" I have to have an answer to that question: with the workshop, if I don't write regularly, I'm not going to be able to bring something in to this workshop of people that I really respect.

I have kind of an addiction to reading how-to-write books. You mentioned it already, but On Writing by Stephen King is one of my favorites — even though I'm not crazy about the books that he's written over the last, uh, you know, two decades or so. What about you? Do you still read writing guides?

Yeah, I love them. I used to think I had to be self-taught, and there was some pride in that. And then I realized: "Oh yeah, there's instructions, dummy! Just read the instructions." I really love Priscilla Long's The Writer’s Portable Mentor. That was one of my favorites from the get-go. Some of the first books I picked up when I realized I wanted to try to be a writer were Bird By Bird and The Artist's Way.

As someone who was a totally lazy and terrible student who always wanted to buck the system, I thought it was a fun game to try to not be educated. And the day I graduated college I was like, "oh, I'm supposed to be educated now. I did it — I bucked the system, but now I don't know anything."

So I'm going to be a student for the rest of my life trying to make up for what a terrible student I was in high school and college. I'm into learning as much as I can about how it's done, but then at some point you have to put the how-to-write book down and actually write. They can be a form of procrastination.

Did you have a specific reader in mind as you were writing the book?

I guess I was writing to myself at age 28, when I had come back from Peace Corps and knew I wanted to be a creative writer. I had no money, I had a day job and a side gig on the weekends, I had student loans. I would try to write for like an hour in the evening. I wanted to gain some traction, but I had no idea what I was doing. I started submitting immediately, which is so dumb. I wrote my first story and I emailed all my friends to say, like "I've become a writer." I don't want to know how terrible that story probably was.

So the book is for the person who wants to try to start writing but doesn't really have a plan, or know how to prioritize what it takes to be a writer.

How has it been, now that the book is out in the world? Are you finding it difficult to shift gears back into writing about something other than writing?

I decided for myself that I want to be a writer who helps writers. But I still need to make sure that I don't lose that artist part, where it's just for the joy of it. I use my writer's workshop only for my art writing. That's my sacred space.

Bringing it back to Lit Crawl, is there anything that you're looking forward to at Lit Crawl this year?

There's so many things. I usually just let the night wash over me, because it gets to a point where the opportunity cost just weighs on you. I like to think that going to things like this is like walking through the forest. You're not going to see every tree, but the trees that you're going to see are beautiful.

The Airstream Poetry Festival is the literary summit that Portland and Seattle always needed

At a time when festivals are getting slicker and more polished and market-tested to the point of homogeneity, the Airstream Poetry Festival is a delightfully catch-as-catch-can affair. Put together by Mother Foucault Books in Portland, the Airstream festival takes over the Sou’wester Lodge and Trailer Park in Seaview, Washington for a weekend of poetry readings, workshops, publishers, ocean walks, and karaoke.

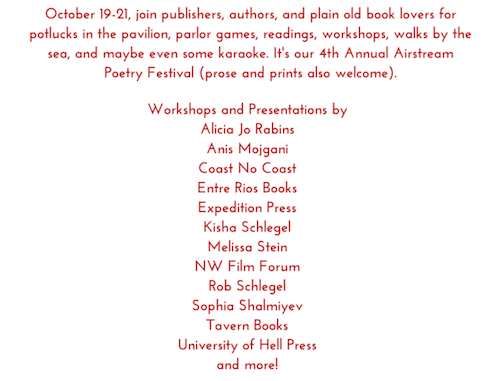

The next Airstream Poetry Festival takes place the weekend of October 19th. Tickets are just $15, and they include a potluck dinner and omelette breakfast at the Airstream's outdoor kitchen. I talked on the phone with Heather Brown, the events organizer at Mother Foucault, about the four-year old festival. Brown says Airstream started as "a retreat for personnel and friends of the shop. It's been gradually becoming more official" in the intervening years, she says.

While originally the weekend just featured a single reading with poets like Matthew Dickman and Carl Adamshick and Ed Skoog, Airstream now blends readings with workshops, games, music, and film screenings (Northwest Film Forum will be in attendance this year with a collection of films curated by Seattle writer Chelsea Werner-Jatzke.)

Aside from the rural locale and laid-back vibe, the thing that makes Airstream especially interesting is the geography of it. The festival feels like a Portland-Seattle summit, since it's located roughly halfway between the two cities. "It's been really great to get interest on both sides toward meeting in the middle," Brown says. But Airstream casts an even wider net than that: Brown says Bay Area poets also take part in the festival, and that publishers Expedition Press and Copper Canyon are both heading down from Port Townsend.

While she's excited for all the events, Brown thinks Seattle Review of Books readers should especially take note of Alicia Jo Rabins, who'll be reading from her new book Fruit Geode. "She's also bringing music," Brown says, adding Rabins "composed a soundtrack for the book that she'll be pioneering at the festival." She's also interested in the typewriter-themed writing prompt that Expedition Press is overseeing.

Another fun thing about Airstream is that it intermingles workshops and readings in an interdisciplinary vibe. Smartly, it doesn't put up artificial walls between readers and writers of poetry and literature. "It's just a fun place to come," Brown says. "It's a great way to meet new people and also be encouraged in your craft, if you're a writer and to meet some writers up close if you're a reader and a fan."

"And also it's not totally writing-centric," Brown says. "It's very, multidisciplinary. We've got a lot of input from various creative streams." She adds, "and it's also just a great getaway."

Talking with Lit Crawl Seattle's planners about their goal to "change...how Seattle views itself"

You're already saving the date for Thursday, October 11th, right? That's the night of Lit Crawl, which is arguably the biggest single event on Seattle's literary calendar — 40 events spread over dozens of venues in one night all across Capitol Hill, with a big dance party to cap it all off.

But you should also save the date for Thursday, October 4th. That's the kickoff fundraising party for Lit Crawl at Capitol Cider, with cocktails, an auction, a raffle, and live entertainment.

Last night, I talked with Lit Crawl managing director Jekeva Phillips and programming committee member Anastacia-Renée about what they have planned for this year's kickoff party and the Lit Crawl itself. The two writers are impossibly busy in their day-to-day lives — Anastacia-Renée is Seattle's Civic Poet and a prolific author, while Phillips is the publisher behind Word Lit Zine and many other projects — So I wanted to know how they also managed to put together the busiest day in Seattle's literary calendar year. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Is this your first year in your current role at Lit Crawl?

Jekeva Phillips: No, I was managing director last year, and this will be my fourth year. I started out at Lit Crawl as a volunteer, handing out pamphlets to folks and directing lines. The year after that I was invited to be a part of the venues and volunteers team, and then the torch was passed.

So that's kind of how I came to be where I am: Slowly but surely going from volunteer to managing director over the course of a couple years. Last year, my first as director, was a lot of fun. It's really interesting on this side of the fence.

Anastacia-Renée: It's my first year being on this side of Lit Crawl. In Seattle, I'm always trying to be the underdog who makes change. And I felt honored that Jekeva asked me to be the part of the programming committee because I felt like that was another way I can make change. I don't mean change in terms of previous Lit Crawls — I mean change in terms of how Seattle views itself.

First of all, I think Jekeva Phillips is one of the most underrated African-American/POC makers and changers in the city. Jekeva does a lot of work, and I don't think she is recognized in the way that she should be. When I heard Jekeva was involved, I said "I want to do that."

Second of all, I think Seattle gets set in its ways — there's a certain idea of what it means to be a professional writer. As Seattle Civic Poet, and someone involved at Hugo House, I've been trying to tell people, "you are missing out on some of the best writers and artists in this city because you have this small point of view of what a professional writer is." Lit Crawl gives me an opportunity to say that just because you don't know about this writer, or because they don't have fifteen books published, or because they're not a cis white male, doesn't mean they're not amazing. I get to help show the community what they're missing.

Jekeva Phillips: Anastacia is always so warm and giving and she always sees the brilliance in people. That's what I wanted to bring to Lit Crawl: different kinds of POC voices, queer voices, trans voices. There are so many writers hiding in the margins of the city, and it takes the kind of person who cares about people like Anastacia does to give them a chance. We love those voices, we love to say "hey, this person is awesome and we should put them on the same platform as everyone else."

For one night we just share our love of books and poetry and nonfiction. We all kind off come together. it doesn't matter if you're a sci-fi writer or a literary fiction writer — we're showcasing that there's always something for everybody, and everybody's got power.

What do you think makes a great reading?

Anastacia-Renée: I really appreciate when I can traverse genres. Even though I'm a cross-genre hybrid writer, people always ascribe me to poetry. But I write non-fiction, I write flash fiction. We're all writers. We don't have to stay in our little compartments. Genre freedom is a must. Free the genre! Free the nipple, free the genre. That's the title of your piece right there. We can be together — we can actually be together on one stage and share our work.

Jekeva Phillips: I also wanted to say everyone has done such a great job and it's been so much fun. It's a great team: Vi Tranchemontagne does programming and venues, Kathleen Flinn works on programming, and Julia Hands does our marketing and PR. It is such a labor of love and we all are laughing all the time. Together, we really put together a really great program.

We'll have over 40 events in one night in different venues. It's very stressful when you think about it that way, but there's no drama. We push boundaries, and we support each other creatively.

Anastacia-Renée: I totally agree. I've been a part of other committees, and I think there's a feeling here of camaraderie and a feeling that I'm safe. I've been a part of committees where i didn't feel safe — I had the sense that I was there only because of tokenism. Here, there's a shared vision of awesomeness — the amazing feeling when you want everyone to succeed.

Jekeva Phillips: Seattle gets caught up in a set way that we think about what it means to be a writer, and we try to challenge that at Lit Crawl.

I really love Katy Davis's design for our poster this year. I wanted something that makes books fun. I don't understand why we think about books as being this nerdy, educated highbrow thing. We should think about books as something fun. They're cool. You know, I've read all the classics, I'm not pooh-poohing them. But I wanted something that's fun, that's urban, that's engaging with a cool vibe. I want people to think about books the way they think about TV shows and bands.

Anastacia-Renée: I think the poster totally captures the feeling of Lit Crawl. I think music-lovers get it more than writing lovers. You don't see anyone saying, "this kind of music is actually the only real kind of music," or "I don't know, I'm only listening to such-and-such right now."

I need writers to get on board with this: The other arts have diversified what they think is special and good. You go to a museum and it's not one kind of art. It's not one thing. It's a lot of different kinds of art.

This is what i love about Lit Crawl: When you think about it, it's the one time of year when I feel that you get the whole Seattle experience for free in one night. It's actually kind of amazing. I know you can't print this, but it's fucking fantastic.

Jekeva Phillips: A big reason why it's free is because of our fundraiser on October 4th. We have fun things we're going to be auctioning off — items with different price ranges. We'll have things on the cheaper side that are better for our writer and artist friends, but we'll also have items like a voiceover class and different works of art.

We wanted to bring some fun stuff to the Lit Crawl fundraiser kickoff party this year, which is why we asked Briq House. She's a body-positive burlesque performer, and she'll be doing a literary/Halloween-themed burlesque dance. We love books, but we also love to party.

Anastacia-Renée: We writers are not all sitting by windows counting sparrows. We like burlesque and we love fun.

Every Lit Crawl, I discover at least one writer who just completely blows me away that I've never seen before. Where do you find these folks?

Jekeva Phillips: I go to a lot of readings and so does Anastacia. And I'm going to give a lot of credit to our programming team.

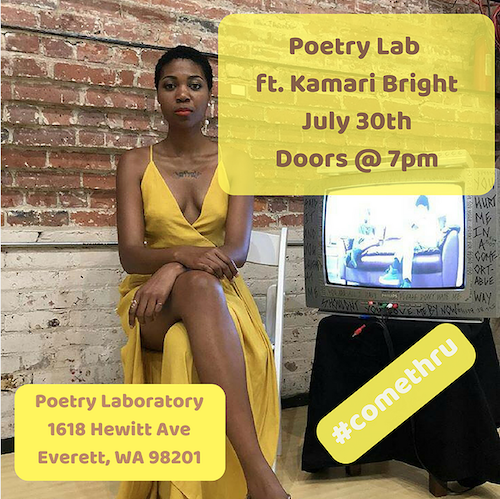

There are whole communities up in Everett and Lynnwood that are doing great things, and if they can come down here for one night and showcase those skills, maybe people from Seattle will start visiting them.

Anastacia-Renée: I think my specialty is finding people who are gems who have not been asked by Hugo House or Jack Straw or Elliott Bay. In fact, I make it my mission. My mission is to find the gems that you don't even know are gems. And then I'm interested in what would happen if two people who are totally opposites read together. Those are my two strengths. I don't always set out to look for POC readers or queer readers or trans readers, but those are often the gems who need recognition.

Jekeva Phillips: Talking about what you said about being blown away: I think the best events always linger. When I leave the reading, I can't forget about what they read because their perspective is fresh. They demand an audience.

Anastacia-Renée: Going back to the music analogy, if you really like a band, you're not going to keep them to yourself. No — you're going to tell people about them. I feel that way about really great readings, too.

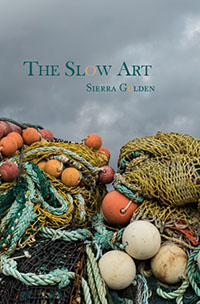

Sierra Golden is finding her way in the world

Our September Poet in Residence, Sierra Golden, is at the very beginning of what looks to be a long and important career in poetry. Her debut collection, The Slow Art, was just published this month by Bear Star Press, but she writes with the confidence and the economy of a poet twice her age. This is not something you see in a young poet: Golden inherently understands that what you don't say in a poem is just as important as what you do say, if not more.

"I was always the student who was interested in poetry, from elementary school through high school," Golden tells me over coffee. But she didn't consider herself a poet until college, when she took a workshop with former Washington state poet laureate Tod Marshall. "I still think it's the best workshop I've ever had," she says.

The first piece Golden turned in for the workshop was a poem about fishing. "I spent eight summers working in a commercial fishing boat in southeast Alaska," she explains, "and that became the focal point of most of my writing for a really long time."

Golden is from a fishing family in rural Washington state — her dad has worked as a commercial fisherman for four decades — and when she worked salmon season one summer to pay for school, "I fell in love with it — just being outside, doing something that gives you really immediate feedback. Either you catch or you don't."

The "eternal optimism amongst fishermen" culturally spoke to Golden, but when she was out on the water, she also felt "an elemental connection to the natural world," and that connection gave her a sense that she had a place in that world. Poetry, then, is how she learned to communicate all these elemental emotions. She loves the form for its way of "condensing life into something small and measurable and meaningful and musical."

Her early influences include Sharon Olds, Jack Gilbert, and (on the more contemporary side) Matthew Dickman. Her reading inspired her to pursue an MFA in poetry at North Carolina State University. Golden wasn't sure at that time if she'd be a poet, but "I knew that [the MFA] would be formative and I knew that if I didn't do it then, I might not ever do it."

After moving to Seattle, Golden felt more and more comfortable thinking about herself as a writer. She took a job as a communications associate at an important local nonprofit. "Working at Casa Latina has probably been more affirming than anything else" in terms of helping Golden think of herself as a writer "because I do a lot of the external writing for them. The staff has been very supportive and flexible over the last four years so that I can work on personal projects."

Seattle has embraced her. Golden was selected for Hugo House's Made at Hugo program, which provides educational and resource support for a cohort of young writers. She finds inspiration and draws strength from many Seattle authors including Anastacia Renée, Daemond Arrindell, Elizabeth Austen, and David Wagoner, and she thinks "more people need to know" Bellingham author Nancy Pagh, a creative writing teacher at Western — particularly her book No Sweeter Fat.

Golden is still coming to terms with herself as a Seattle writer. As much as she loves the city, "I still crave a smaller, quieter, less fast" lifestyle like the one she had growing up in rural Washington. She's branching out into other forms, too. "I'm working on a novel," Golden says, "which I never thought I would do and was never interested in."

Still, Golden is getting "the itch" to return to poetry. Writing about fishing, she says, "made me feel like I was cheating or something because it's so visceral and it's really easy to write about it." While the poems in The Slow Art at times feel like journalism, her "next challenge," she says, "is going to be how to write about something less concrete that has the same meaning." Considering all that Golden has accomplished so far, it's obvious that she'll find her way. She always does.

Talking new fall titles with one of Seattle's best booksellers

Caitlin Luce Baker is one of Seattle's very best booksellers and one of the most avid readers in the city. She works as a backlist buyer at University Book Store, which she helpfully explains to me over the phone means she's in charge of making sure the bookstore carries "the books that came out last week, and the books that came out fifty years ago." Caitlin frequently represents the city at national programs — she's currently a judge of the 2018 Best Translated Books Awards — and she always reads months into the future.

"I probably read 12 to 15 books a month on average," Caitlin says, and she tracks every book she reads by noting them on three-by-five inch index cards. All those books you're dying to read this fall? Caitlin probably read most of them months ago. (She's an excellent Twitter follow as well.)

So what fall titles are Caitlin most excited for you to read? The first book she recommends is a short story collection by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah called Friday Black, which Caitlin says "blew me away. He's a dramatic new voice," she says, and "there's not a weak story in the bunch."

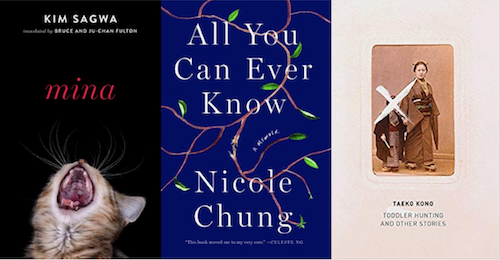

Caitlin calls another upcoming collection, Toddler Hunting and Other Stories, by Taeko Kono, "unsettling and obsessive." The title story, she says, "is about a woman who loathes little girls, but is always buying expensive clothing for little boys of acquaintances." Kono is interested in crossing boundaries and violating taboos, and Caitlin warns that "each story in this collection is dynamite."

"Absolutely one of my favorites" of the upcoming fall titles, Caitlin says, is a novel titled Samuel Johnson's Eternal Return, by Martin Riker. It's "the story of a father's love for his son" that "traces the history of television in America." At the beginning of the book, everyone watches the same three or four channels, but by the end those choices have fragmented into "a zillion channels," which results in a kind of loss of community.

Another novel that was just published yesterday, The Golden State by Lydia Kiesling, looks at another angle of parenting. "It's a road trip novel, but it's different — it's a road trip with a 16-month old baby," Caitlin says. The book is about a woman whose husband is Turkish, but "due to US policy and visa issues, he's back in Turkey." Life as a single mother becomes overwhelming, and "she takes off in her Buick to a small town in California," where "she meets a woman who lived in Turkey when she was younger." Caitlin especially admires this book for its timely investigation of "questions of American immigration."

Caitlin calls Mina, a novel out on October 10th by Kim Sagwa and translated from the Korean by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, "one of the rawest and most honest depictions of what it's like to be a teenager" that she's ever read. "This book takes it to extremes," she says. "There's a screaming kitten on the cover. I don't want anyone to pick up this book because it has a cute cat on the cover — that cat is screaming for a reason," Caitlin warns. "This book kind of blew me away."

The fall brings with it some vivid first-person accounts that will open readers up to new perspectives. One of the titles that most appeals personally to Caitlin is Shaun Bythell's Diary of a Bookseller. "It is hysterical," Caitlin says. "Anything that anyone ever wanted to know about what a bookseller really thinks is in here." It's about the owner of a bookshop (named The Bookshop) in Scotland and his relationships with customers.

As much as she loved Bythell's memoir, Caitlin says of Nicole Chung's All You Can Ever Know, "if you read one memoir this year, read this one." She says the language in the book, which is about Chung's experience as a Korean girl who was adopted by a white family in a lily-white Oregon town, is "beautiful." Chung took the solitude of growing up where "no one around her looked like her" and channeled it into an intense memoir that investigates race and identity.

After talking on the phone with Caitlin about upcoming releases for a half an hour, she sent me a followup email with upcoming poetry titles that she wants people to know about — The Carrying by Ada Limón and feeld by Jos Charles, both from Milkweed; and Perennial by Kelly Forsythe from Coffee House. Her exuberance for the titles is infectious. For the better part of a year now, she's been waiting for readers to be able to get their hands on these books, and finally the time has arrived. For a dedicated bookseller like Caitlin, fall book season is one of the very best times of the year.

Elizabeth Austen is finding clarity by embracing mystery

I've been following Elizabeth Austen's work for years now — from her early chapbooks to her 2012 debut collection Every Dress a Decision, from her role as Washington state's third Poet Laureate to her role as a poetry correspondent for KUOW. Her poetry has always been accessible enough to capture a reader's immediate attention, but durable enough to reward multiple readings with new discoveries. She's a complex writer who constructs levels in all her poems.

The four poems Austen contributed to the Seattle Review of Books this month as our Poet in Residence, though, feel different somehow. It's not that Austen doesn't sound like herself — that voice is as clear and confident as ever — but the rhythms of the poems feel different, and there's a mystery to the new work that departs from her previously published material.

On the phone, Austen admits to being "relieved" when I ask her if there's a difference between her new and her old work "because they seem different to me. And I want them to be different." But she's not entirely clear on what the difference is, either.

In many ways, Austen is just recovering from her time as Poet Laureate — a role that awkwardly fuses the sociability of a politician with the introspection of a poet. Austen was a tremendous advocate for local poets and a very effective conduit between ordinary Washingtonians and the literary arts. But she says her two years in office were "draining in a way that I don't think was possible to anticipate." Austen says she "loved" being Poet Laureate and "I was grateful to get to do it," but she confesses that "I needed about two years of quiet" when her term was over.

Of course, nothing has been quiet about the last two years. Austen says her newer work is "partly dictated by the times we live in." Since 2016, she's been "feeling silenced by my own sense that poetry seems an incredibly paltry response to the state of the world."

This isn't just about a Seattleite despairing at Trump's election. Austen says her poetry was silenced in the face of "the resurgence of something ugly that I thought was a lot closer to its deathbed: overt racism, overt misogyny, this incredible xenophobia and anti-immigrant insanity."

After months of feeling helpless, Austen says she came to terms with her responsibility as a poet: "I finally just gave in and realized that it may be paltry, but it's what I have to offer."

As a reader of poetry, Austen says, her needs have changed. "I need poems that speak to the moment we're living in," that provide a context to modern American life as part of a continuum of history. Who does she read for inspiration? "Danez Smith and Terrance Hayes are two poets that are just continually rocking my world in terms of what they managed to do with the clarity and imagination with which they're meeting the moment." She credits Ada Limón for being "willing to hold the heartbreak of moment."

But in order to find her inner voice again, Austen has had to reach outside herself. "It feels very practical when I bring poems to groups of people who, for example, do palliative care or who work with people who are unhoused," she says. (In her day job, Austen works as the senior content strategist at Seattle Children's Hospital.) "The value of poetry feels very urgent and very tangible to me because I see it through the eyes of people who don't have the kind of everyday access to poetry that I do." By sharing poetry with people who are experiencing grief and trauma, Austen remembers why poetry matters.